Artists Discuss: How Cultural Identities Inform the Creative Process, Part 2

by Kalila Kingsford Smith

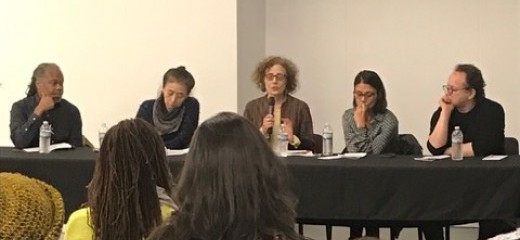

On November 14, 2016, students of dance and choreography gathered at Gibney Dance for a panel, organized by New York Foundation for the Arts, to discuss how cultural identities inform creative processes. Moderated by Wendy Perron, the panel included Reggie Wilson, Eiko Otake, Patricia Hoffbauer and Zvi Gotheiner. In the aftermath of the presidential election, young attendants at the panel were desperate for guidance about what artists are to do in a changing political environment, so while the moderated questions focused on cultural origins and expectations, the conversation strayed into more explicitly political discourse. What ensued was a series of conversations highlighting the differing cultural impositions that these artists navigate, as well as a discussion about what it means to have an American identity when you originate from a different country. The following is Part 2 of a two part series compiled and edited from the event’s transcript.

Audience Understanding and ‘Explaining’ Your Work

Audience 1: I do Native American work, and I have come across the difficulty of [audiences] not understanding the work. They don’t know the background of most of what I talk about, they don’t know history, they don’t understand culture, and they don’t “get it” a lot of times. The other thing is that because you’re dealing with the traumas of your own past, sometimes you don’t know that you’re hurt until you’re in the studio working with each piece. So I guess I want you to comment on that process. How do you work with that material? If you come from a very specific place, how do you deal with that? How do you choose not to explain yourselves sometimes, and just go for the art and the beauty of the sound or the movement?

Reggie Wilson: I think it’s a lifelong process, and as a choreographer and an artist that is something that you will [always be working with]. It’s not going to disappear, the same way that trying to find music for a dance is not going to disappear. It’s an ongoing relationship. Like Blondell Cummings’ piece Chicken Soup: she made this wonderful, gorgeous piece that was well celebrated, but she kept finding people who thought the piece was about black women and servitude, and that she was being a maid. She made the piece as kind of a memorial to her mother and her aunts in the kitchen that she grew up in. That [perception] really devastated her, but for that particular piece, the way that she was able to deal with it was with a program note.

I tend to hate excessive program notes. Sometimes it’s really good; sometimes it’s really bad. I think it’s up to the choreographer to keep figuring out what is important for the viewer to get. I personally give it up and try to give them other things. I have a duet with two dancers in my company who have worked with me for a long time. I never thought about it—and maybe I should have—but people kept [referring to that duet as] the little white Jewish woman being raped by the big black Jamaican guy, and I would say, “Ooh. What? Huh?” [laughter] “Okay, rape, nice, yeah—oh that’s right because black men are supposed to be… right.” There are so many layers. I’ve done a piece where it’s read one way in Milwaukee, a different way in New York, a different way in Trinidad and Tobago, and a completely different way in Zimbabwe. You can’t control your audience and viewer. So my recommendation—I think there’s a billion different ways you can do it—is to just do whatever the fuck you want to do. [Applause]

Eiko Otake: I have been doing daily performances in the Cathedral of St. John the Divine. Nobody has money there, but I have a space and lots of tourists everyday who ask questions, and you can choose, how much do you want to answer. If someone asks a question with a very straightforward curiosity, I actually try to talk about it. I’m actually learning about them, their different backgrounds. But it’s good to know what other people think. You can’t really be alone. You are responsible for what happens. We aren’t responsible for what people think, but what happens is a part of how people think various different things. So I’m curious about that, and I think curiosity is okay, we don’t have to solve it tomorrow.

Zvi Gotheiner: The world changed. Something is different. For me, I feel like if I have any direction for myself, it is to go back to the body, to find consciousness in the way you live your life, and for us to find a way to tell the human story more accurately. This election process was so unbelievably ugly that you want to duck underneath the table and not show your face. But we should be clear, look at the big picture, look at inefficiency in the way we respond to it, in the way that we don’t waste energy on inner fighting, make sure that progress is progress, that we’re not going backward and when it is necessary to get mobilized, we get together and mobilize.

Identities Self-Defined and Imposed

Audience 2: Has there actually been a solid point when you said, “this is my cultural identity”? Or maybe you look back: “that was when I started to form my definition of my identity.” Do you feel like that’s something that’s always evolving? Do you feel like that’s something you discover through your dancing and creative work? Have you found one or a few identities that stick with you?

Wendy Perron: I just want to say that I think when it’s printed like this—cultural identity and creative process—it does seem like cultural identity is a fixed thing, but it’s not. Eiko was saying that she has a different cultural identity from her mother, so I think these things change all the time.

Patricia Hoffbauer: Yeah, when I speak about Whiteness or when I speak about Brazilian-ness or Latin American-ness, all of that is an antagonistic definition. It is a definition that exists because I’ve been seen or called that. There’s that, and then there’s also racism and real misogyny. So you have to know for yourself. When do you have a clear identity—either to the world or to yourself? But it should never be a straitjacket to you. You should never allow anybody to define you.

Reggie and I have been in many situations in the “multi-culti” years where we were defined, and we were asked to be in showcases because “you’re a woman in this, or a person in that.” It was coming from a cultural policy that was asking artists to fulfill certain kinds of roles. Looking back, I actually think there were some good things [that came from assuming] the identities that were given to me and then to go against that, criticize it, be sarcastic, and parody it. It’s important to know how you are being perceived. I don’t mean that you have to interview your audience, but you should know if your work is totally hermetic, nobody gets it, nobody understands it. And that’s ok, if that’s what you want, but if you’re trying to make something clear, and it’s not [then you should know].

Artists Engaged in Listening and Disagreeing

Audience 3: I’ve found myself in the past few days thinking about how to deal with people who I disagree with. Right after the election, my instinct was to go out there and talk to people I disagree with. So I just wanted to ask: how do you deal with disagreement, whether it’s about your art, or your citizenship, or people who you disagree with?

PH: I do think it’s hard, but I think the important thing is to listen, and I think that’s the only way forward, to not pretend that we all agree. I think that I’ve learned so much in the last ten years in my classroom—I’ve had Palestinian and Israeli, I’ve had black and white—completely different positions, not just nationalities, but politically they’re different. There’s an understanding that you’re supposed to speak in a certain way [when you disagree], so the classroom is a good environment to have those conversations in.

EO: In my first ten days here I met about eight people who vocally said, “I disagree with you.” I was so impressed because in Japan, people don’t say they disagree. So this is a great asset [to have as an American]. You can actually say, “I disagree.” [Someone helped me by telling me that] when you say, “I disagree,” you should make sure that your face muscles aren’t too tight. This is the body language that I learned and it makes a big difference. Instead of saying, “I disagree” [Eiko leans back crossing her arms, tightening her face], say “I disagree” [Eiko leans forward, opens her face]. Then you are already allowing for the conversation to happen. This is something I’ve been working on myself.

To read Part 1, click here.

New York Foundation for the Arts: Cultural Identity and Creative Process Panel, moderated by Wendy Perron, panelists: Reggie Wilson, Eiko Otake, Patricia Hoffbauer and Zvi Gotheiner, Gibney Dance Center, Nov. 14, 2016.

By Kalila Kingsford Smith

March 26, 2017

.png)