Lindsay Browning took her inspiration for Lincoln Luck from fertile ground: her childhood exposure to performance, the imagined life of Abraham Lincoln had he not been assassinated and/or had a daughter, and the general idea of “what if’s” and the role of luck in life. Not to mention her relationship with her father, her time in a foreign country preparing her first evening length work, and plenty of collaborative artists (listed on the show’s blog as “a creator, an actor, three dancers, a musician, a video artist, and a young boy 7 years young.”) Perhaps the ground was too fertile.

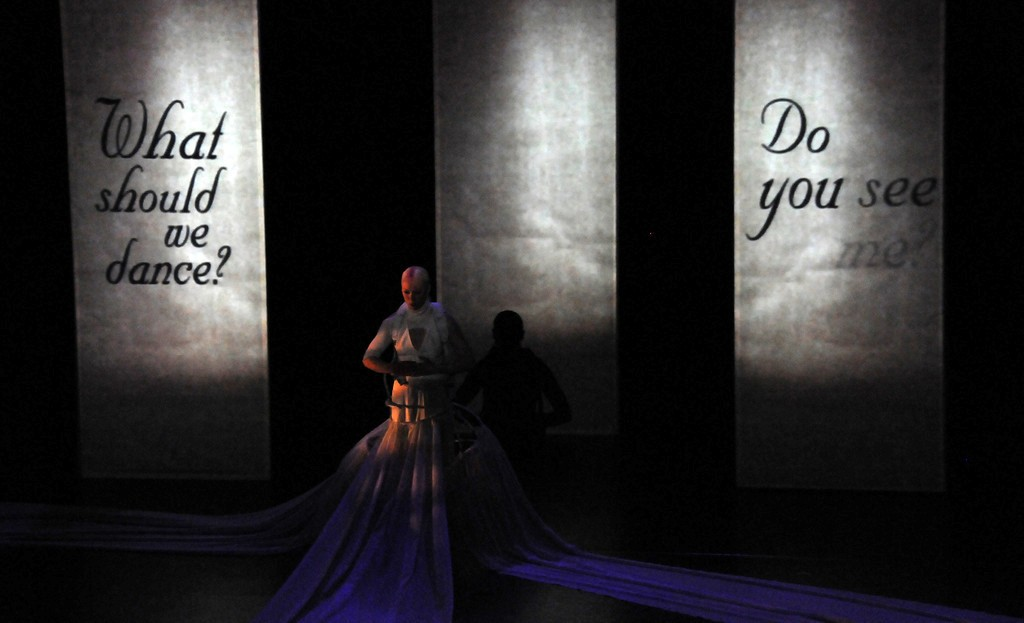

After a brief introduction to David Browning’s Lincoln character in the Painted Bride’s café, we follow him into the theatre to find the stage masked with fog and enveloped by Lindsay Browning and her costume, which includes three white panels that extend to the edges of the stage. Another three white panels hang behind her.

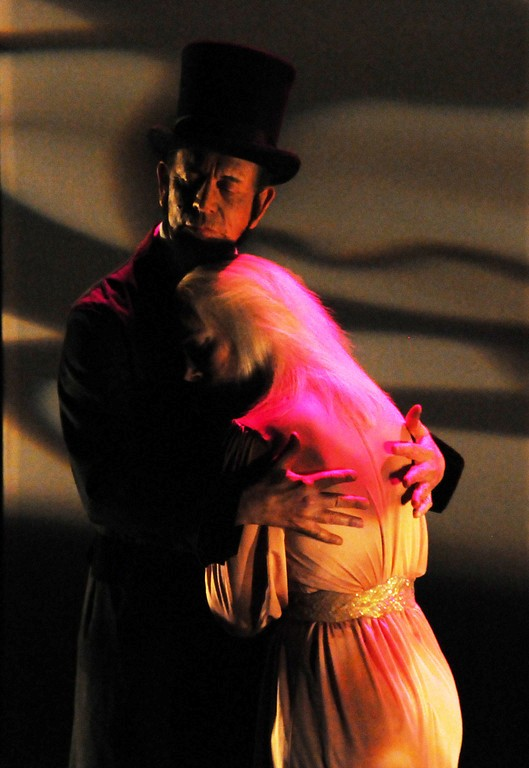

As David Browning looks at his pocket watch, she begins tiny snake-like arm movements, revealing one hot pink glove, until he puts the watch back in his pocket. The contrast between her alternating stillness and sharp movements is breathtaking and curious.

It’s clear she’s closely tied to Lincoln, but how? Who – or what – is she?

She crawls raptor-like out of her contraption, the visceral tension in her body captivating. Now alone and free, she sinks deep into squats, reaches up with stretched hands grasping, and frantically wipes at her arms, torso, legs. Her costume is distracting. Part ladies suit vest, part torn turtleneck, part pirate wench skirt, it seems significant, perhaps symbolic, but the disparate components are confusing.

Later, Lindsay Browning and John Luna execute a meticulous dance with pocket watches, spinning them in circles with graceful halts or like nunchaku. Then in a gorgeous but perplexing set of video projections, we see child Lincoln (Tommy Burkel) and young adult Lincoln (Luna) in a series of scenes walking off in silence and bright light, taking hats on and off, removing and dropping notes. Again, these seem symbolic, but as they’re not picked up elsewhere in the piece, it’s hard to discern where they might point.

Then the stage goes dark, and a hesitant young voice reads Thomas Gray’s “Elegy Written in a Country Church-Yard,” a lovely but long and unrelated meditation on death and remembrance. “Elegy” makes some references to fate, but is not significantly tied to Lincoln or “luck” – a more conspicuous use of the poem throughout the piece could have given a clearer sense of its purpose. Suddenly, the panels fill with choppy brightness and a video of the crouched, shrouded figure of Myra Bazell, accompanied by guitar and splashing sounds. We see close-ups of her laughing, her hands – she seems otherworldly and trapped in the projections. It’s a stunning image, but also perplexing and disconnected.

Lindsay Browning returns in a cocktail dress, and David Browning follows. Her dancing plays off his spot- on Lincoln gestures in a moment of pure bliss. Luna replaces them and leaves a pie and a watch front and center to perform a brief tumble-y solo that recalls Lindsay’s earlier squats and stretches. Then he picks up Lindsay’s earlier-discarded vest and leaves his own. It’s not clear if this is a comment on a change for Lincoln, a change for Lindsay Browning, or something being exchanged between them.

Finally, Lindsay Browning returns in her own Lincoln attire. She lights the pie’s candles as David Browning enters with the white balloon and pink glove from the café. Standing next to each other and facing us, they exchange – she puts on her matching glove, and he blows out the candles.

Setting aside a baffling letter read in Italian, each component of the piece was rich and lovely, but without a clear thread to link them, it often felt like a barrage of compartmentalized symbolism. Lindsay Browning has convened many talented collaborators, but the discerning outside eye of a director or dramaturg might better pull together their stunning yet disconnected visions.

Lindsay Browning’s Lincoln Luck, Jonesy Dance Theatre, Painted Bride Art Center, Feb 10-11. No further performances.