A group of men, draped in burnt-orange garb, slowly tapped their palms against their bare chests. Polyrhythms spread into their strong, muscular legs. Responding to the depth of each breath, each sung word, each stomp, I got chills as the speed and complexity of the rhythms intensified. I had to double-check my program. Had I gone into the wrong theater? These dancers resembled a hybrid of steppers and chanting monks. As their Fa’ataupati, or Samoan slap dance, progressed, I began to see the richness of Black Grace’s cultural identities emerge. I was in the right seat.

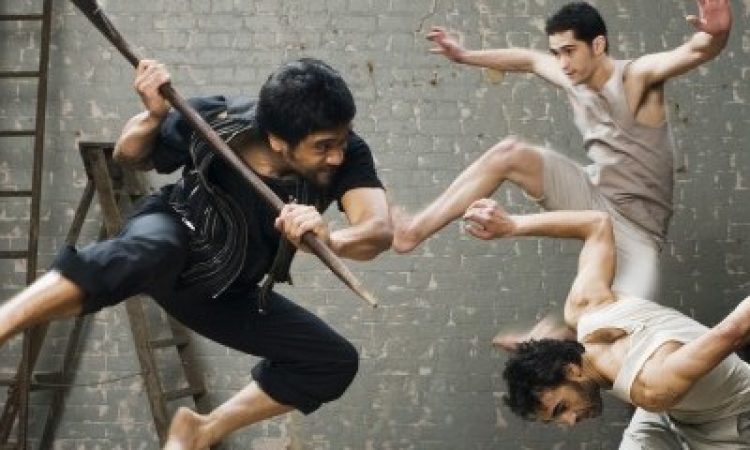

Director and choreographer Neil Ieremia’s use of simple movement allowed me to enjoy the elaborate intricacies of overlapping rhythms as well as the control and ease the Black Grace dancers maintained in moments of hyper-speed.

Ieremia, a first-generation New Zealander born to Samoan immigrants, began dance training at age 19, graduating in a few years from the Auckland Performing Arts School and dancing with the Douglas Wright Dance Company until 1996. His work with Black Grace intertwines storytelling, varied cultural perspectives, and contemporary dance. The company, established in 1995, consists today of seven men and three women of varying national heritages. Ieremia’s Pacific Island roots continue to inspire his internationally acclaimed work.

Gathering Clouds (2009), the 60-minute work that comprised the entire second half of the show, spoke to the director’s cultural and personal history. Each of the three sections used culture-specific images, costuming, sets, and sound accompaniment (created by body percussion, spoken word, or music drawn from Bach, hymns, or Elvis). The piece harbored themes central to Pacific Island migration, taking as its inspiration xenophobic claims about Samoan immigrants’ laziness and their subsequent drain on New Zealand’s economy, as presented in worldwide media. In addition to drawing on contemporary-infused, traditional Samoan movement, Ieremia pulled from his own life experiences as well as from Bruce Lee’s struggles as an Asian actor in America. His crossbred movement repertoire highlighted both his national pride and his concerns over the politics of immigration and citizenship, issues that remain alive today, in New Zealand and elsewhere.

Larger-than-life puzzle pieces, each bearing the partial image of a group of unknown children, floated across the stage, carried by company members. A later scene showed Ieremia as a school teacher before rows of students who, in a matter of seconds, were running from danger, victims of the dawn raids of the 1970s. In these terrifying midnight raids, police seized Pacific migrants who stayed past their work permits, and thus became scapegoats for the country’s high jobless rates. In the dance, a woman in a traditional costume gently articulated her hands, like sign language in water. Silently, she swayed her body behind Ieremia, standing in a black button-down shirt and dress pants. He barely moved until, with the stage lights closing in on him, he began running in place, the small spotlight in the darkness making his journey feel endless, with no clear destination. For Ieremia, the running symbolized moving forward in life regardless of setbacks. As he ran, he announced, “I am proud to be a Pacific Islander, a Samoan. Equally, I am proud to be a New Zealander, a Kiwi. I am blessed to be able to raise my children here, and there is nowhere else in the world that I would rather call home. Despite our struggles, it is in this land and under these Gathering Clouds where I will learn, live, and love.”

The puzzle pieces connected and the stage-wide image materialized: a group of native children in front of a schoolhouse. The audience responded with applause, some with tears. Black Grace enlightened me about South Pacific Islanders’ struggles, while also reminding me that the policing of “alien” bodies is a contemporary, global problem. In that one running instance, I felt his struggle, pride, and determination, and I was with him.Black Grace, Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts, February 12-14.