The opportunity to personally experience a sampling of Trisha Brown’s early works twice—once in the mid-seventies when they were created and then again recently at the Barnes Foundation—presents an occasion for thoughtful reflection through a wide-angle lens. At 20, when I first saw Brown’s work in New York, my personal physical artistry, along with a sense of qualitative discernment regarding dance in general, were in the early phases of gestation—nuance was to small as “ta-dah!” was to spectacular, and I held minimal regard for anything in between. Much of Brown’s work in the early years (and ever afterwards) embraced the engagement of the mind, with little attention— or so I thought—to big, physical manifestations thereof. I have lived long and deeply enough inside and outside of dance to admit (and embrace) my error in judgment. Then again, I’ve always been a late bloomer….

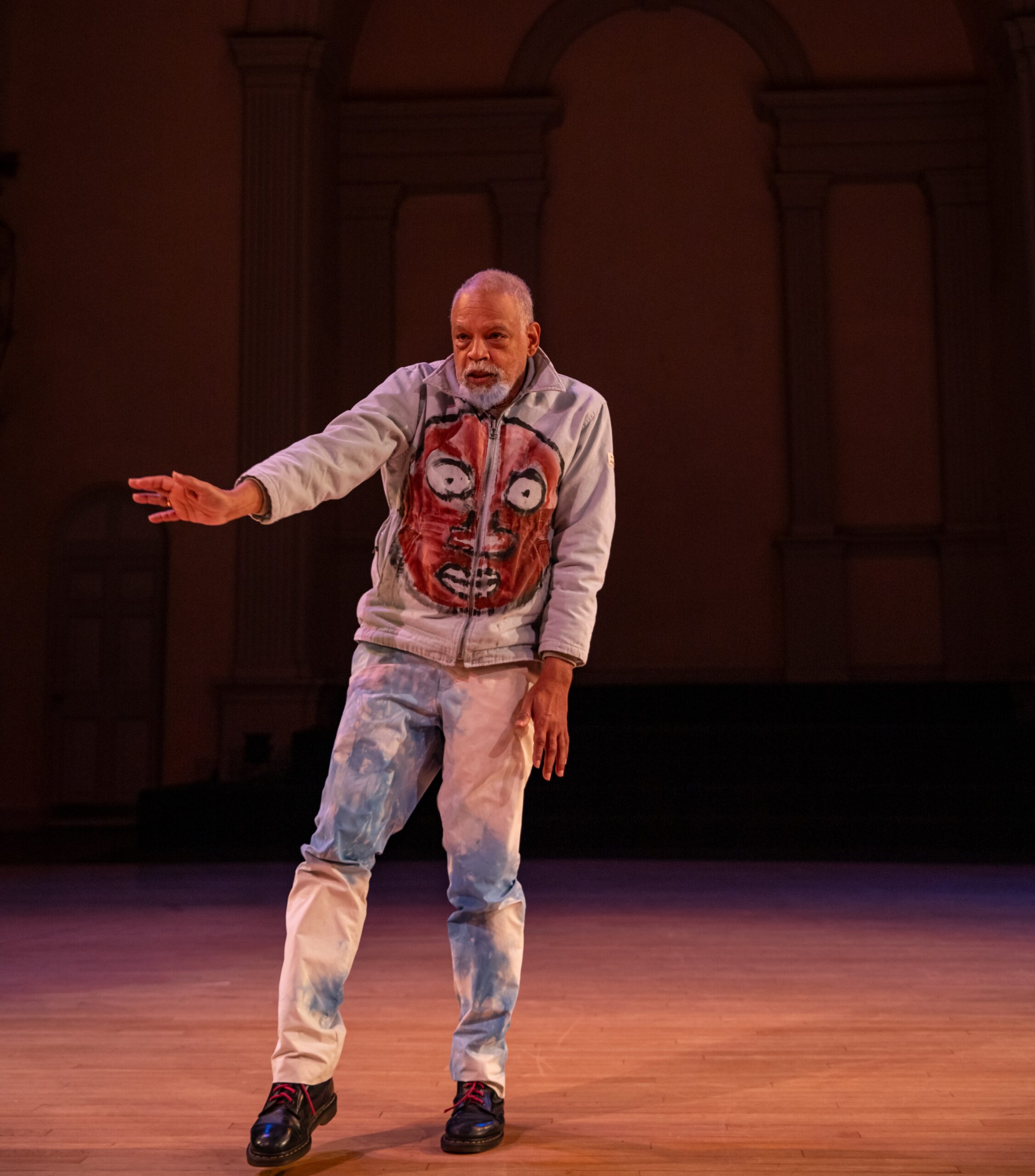

Nearly a half century later, seeing Brown’s early works help us understand and appreciate the visionary nature of her mindset. Brown’s appetite for asking questions in an endless search for multiple possible solutions remains voracious as ever. This investigative bent, combined with her tongue-in-cheek humor, keep Brown and her company relevant and present in the dance scene. At the Barnes I witnessed the product of a sharp mind and body of the ’70s executed by young, vibrant, eager, receptive today bodies. I saw all the nuance, abandon, ownership, focus, virtuosity—all the fervor and “ta-dah,” if you will—I so cavalierly (dis)missed in my youth.

The early ’70s pieces remain stridently current, thanks to the timeless quality of Brown’s work. They display her study of formations and geometrically tight or loose use of the space, while her insistence on natural yet precise and honest movement underlines the the works’ sharp intellectual bent. Dancers lined up to execute simple and mesmerizing arm movements in Figure 8 are in perfect synchrony yet seem to be soloists. Walking on the Wall and Leaning Duets are inquiries about space, time, and relationship. Like her more recent creations, Brown’s early works stand as testimony to great study and practice, to great belief in self.

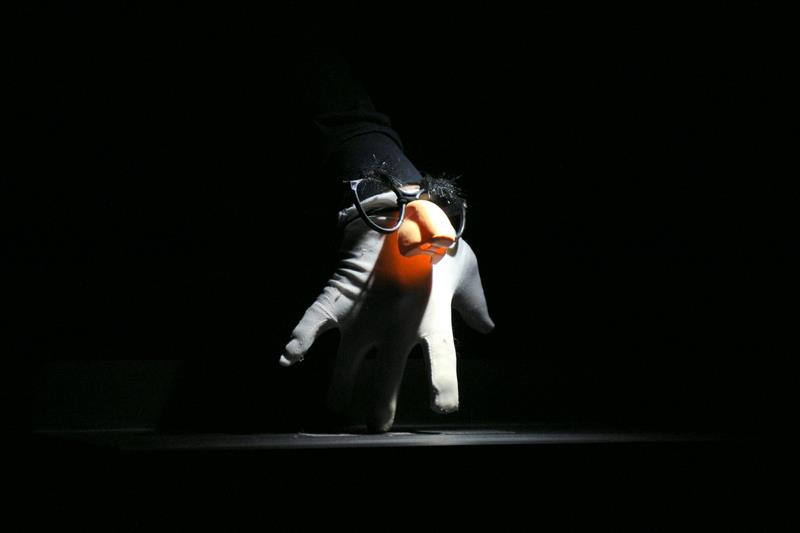

Brown’s understanding and use of space begins with her fascination with the falling and rising body and its intersection with space. At times, her movements seem to emerge from the space itself, the full frame stretching as body parts extend, then succumb to impetus from the smallest gesture, ultimately influencing the architecture of both the movement and the space. The dancers seem to paint their environment, utilizing arms, legs, and full body as brushes. Clear movement execution nudges nuance to the surface, freeing us to enjoy gesture in its most abstract sense. Petite and quirky personal movements and pedestrian postures infiltrate even the simplest of phrases, and the repetition and accumulation of movement sequences can be mesmerizing, like repeating the same word over and over until it acquires another sense. Sooner or later you may be sucked in as I was, heady at the complexity born of unadorned straightforwardness.

The unabashed bareness of Brown’s earliest creations lets us follow her journey of questioning. Straightforward subtlety and understatement populate well thought-out structures. In Group Primary Accumulation, dancers move or are moved either nearer or farther from one another, sometimes overlapping bodies to create layers of relational meaning based on proximity as narrative. Changes in levels and planes play with one’s mental and physical perception of space, place, and motive; the audience is invited to think. Leaning Duets investigates gravity, leverage, and suspension, while Spanish Dance walks five lined-up women into a compressed space (human zip file?) confining enough to press pelvis to buttock, breast to back, cheek to hair. Nothing new? Well, remember the timeline.

The consummate take-away? Monday morning’s subway commute, where I saw passenger-dancers shifting seats, bending elbows, reaching up, passing through, pushing towards and shoving back. Dance every minute, always, everywhere—even in the stillness. Wow. Thank you, Trisha Brown.

Early Works, Trisha Brown Dance Company, the Barnes Foundation, October 18.