Jane Comfort’s new, untitled work-in-progress makes for glorious people-watching. Continuing her departure from narrative-based dance theater, the piece abstracts the experience of urban living, with its persistent spatial negotiations and blurring of public and private realms. The work is minimalist and formal at the outset, and this simplicity allows for close looking. Unlike meeting strangers in the street or on a crowded subway, staring is invited here, thanks to darkened house lights at the American Dance Institute. Comfort’s work centers itself around the way we look at people, particularly strangers. She highlights humanity on a collective scale, showing individuals living in close quarters in urban spaces, navigating shared terrain.

The work begins starkly, in silence, with dancers accumulating onstage. They walk simply, traveling in right angles, tracing grid formations on a white Marley floor. Their steps are highly choreographed, and structure seems intentionally exposed. Performers narrowly miss colliding with one another due to careful calibrations. Spaces between bodies are sized just right. These smooth relationships eventually falter and are interrupted by occasional awkward hiccups—also choreographed and intentional, but representative of spatial miscalculations familiar to most city-dwellers. The performers throw agitated looks at each other. How inconvenient, how embarrassing, to have to negotiate space with another human. Then the bumps and stutters dissolve into unison, dancers simultaneously tracing elegant loops and circles with their steps. It’s a lesson in emergence, the harmonious patterns arising out of disorder the way flocks of birds organize out of chaos, consolidate, and lift off to traverse the same path.

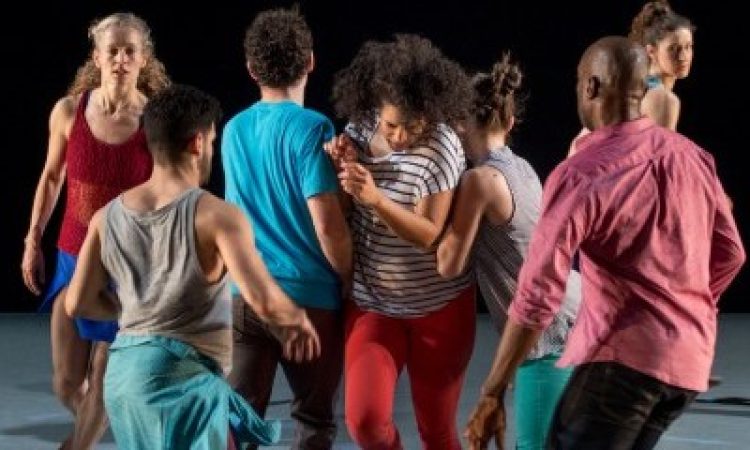

Comfort highlights relationships, and the performers are always tuned into each other’s presence, whether they are collectively internal, moving in slow motion and immersed in their own inner worlds, or playfully jostling, poking, and flirting with each other. When they are not interacting with each other directly—clustering into duets and trios and intertwining limbs—they are linked together by their shared environment. Intermittent video (by Lianne Arnold) appears on the back wall of the theater in whirring and flickering cityscapes. An animation of a subway car arriving at a station and then leaving again gives me a brief sense of melancholy, as I’m reminded of the loneliness sometimes present in urban living. Surrounded by humans and potential connections, temporal realities can make it feel like missed opportunities abound.

However, Comfort focuses more on the potential of human connection in all of its beauty, as well as absurdity and fallibility. A score by Brandon Wolcott, which for the majority of the work consists of sparse electronic layering, opens up towards the end into full-on dance-party mode. Dancers line up to bust a move, awaiting judgment by dancer Javier Perez. Each passes with flying colors, unbearably cool and powerful, save a hilariously awkward, gangly Gabrielle Revlock. A club scene ensues, six performers glowing with sexiness, while Revlock flails joyously and unselfconsciously, twerking and bopping around the outskirts of the stage. It is terrific to be able to witness these human connections and misconnections, with my seat in the audience providing me an almost ethnographical distance from the scene. How strange, funny, creative, and beautiful we humans are.

The distance also feels cinematic. Like camera lenses zooming in or out, panning right and left, Comfort’s work offers a sense of micro and macro to the urban environment crafted onstage. Individuality is celebrated, and yet we can never be isolated, or truly alone. As the music fades, and dancers leave one-by-one, the New York City skyline appears with the sun rising behind it. My usually sensitive “sentimentality alert” button doesn’t go off—instead, I bask in the warm glow of the image, hardly able to keep from smiling.

Untitled Work-in-Progress, Jane Comfort and Company, American Dance Institute, March 18-19.