Up is down. Black is white. True is false. Myth is science. What better moment to anticipate carnaval, consummate ritual of inversion, than a month into the bizarro reality of a Trump presidency? In their recent concert, Balé Folclórico da Bahia brought the packed Merriam Theater to its feet with a heart-stopping extravaganza of Brazilian dance and music, showcasing bona fide “alternative facts”—dance is sacred, black is beautiful, heaven is on Earth, gravity is fickle at best.

The region where most African slaves entered Brazil, Bahia is the center of Afro-Brazilian culture and history. Since its founding in 1988, the 32-member dance company has been celebrated at home and abroad, receiving the “Best Dance Company in Brazil” award four times from the Brazilian Ministry of Culture.

Swirling confections under their oversized petticoats, women in white bend and twirl through the space like giant wedding-cake tilt-a-whirls. Practitioners of Candomblé—a syncretic religion derived from the merging of African traditions brought by slaves, Roman Catholicism, and indigenous practices—they dance the spirits onto Earth in “Origin Dance.” They pepper a rake-thin man with white paint, each cross, polka-dot, and circle on the brown canvas of his skin hinting at Brazil’s particular racial ideal of café com leite. Prone on the floor, he rises to salabhasana, shudders profoundly as the orixá shimmies in through his shoulders. His eyes roll back, white on white, like blanks on a slot machine. Possession.

This interpretation of a Candomblé origin tale opens the two hour-production that also features samba, capoeira, samba reggae, and Bahian folk dances, presented by a stunning cast of 16 dancers, three singers, and five musicians. With no intermission, the music is a near constant presence. While percussion is key to the polyrhythmic heart of the raucous, high-energy affair, transitions between pieces allow moments of reprieve where soloists shine. Bedecked in magnificent floor-length robes and towering geles, singers Dora Santana and Miralva Couto evoke African queens, their booming voices permeating every inch of the theater. Musician Fábio Santos dazzles in a slow-building berimbau solo that echoes capoeira’s loose form.

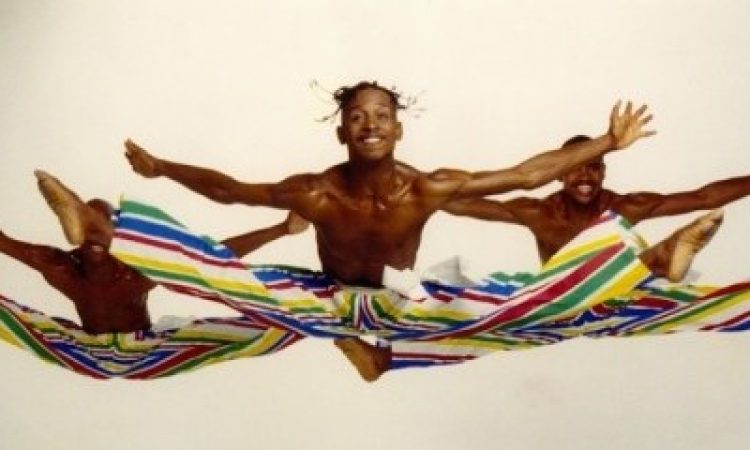

“Capoeira” evolves from playful sparring to full-on battle with gravity. One after another ripped male dancer flips front, side, and backwards clear across the stage, their colorful Adidas-clad legs seemingly propelled by rocket jets. Aloma Silva enchants as sea goddess lemanjá in “Puxada de Rede” (Fisherman’s Dance), her face obscured by beads that quiver with each wave rippling out her arms. Villagers swoop straw hats to the earth, supplicating their catch into being as Silva envelops them beneath the sheer net of her giant hoop skirt. In “Afixire” (Dance of Happiness), an homage to Brazil’s African heritage, the women are topless under brilliant floral collars, and they soar joyfully amidst the loose strips of red, yellow, blue, and green fabric in their flyaway skirts.

As the night progresses, the concert becomes more of a party, the line between witness and performer less rigid. An audience member is plucked from the crowd in “Samba Reggae,” and the singers fête her quick-fire moves with high-pitched shrieks. The dancers descend from the stage and the cast invites the room into a call and response. We groove at our seats and down the aisles, clap and sing along, then explode in praise as the drummers toss their sticks into the air with the last drumbeat.

______________

Reverence and government support for cultural expressions of the country’s African heritage are noteworthy and laudable. Despite Brazil’s historical approach to race relations—records of the slave trade were burned and miscegenation was embraced as a national policy that would “whiten the population” and “erase race”—the country remains ravaged by inequalities that break down largely along color lines.

What is the meaning of carnaval in such a world? Is there value in flipping reality on its head, even if the celebration is short-lived, if nothing changes in the end? What will Brazilians miss in 2017, now that 48 cities may cancel carnaval festivities due to severe economic constraints? Will it live on in staged events like those of the Balé? What does it mean for audiences like us, in the U.S., at this moment of stunning national ambivalence toward other cultures?

For all my enthusiasm, much of the night, I’m not entirely sure what it is I’m watching. Likewise, when I tune in for yet another Trump press conference, I see his mouth moving, I hear the words come out, but I can’t seem to piece them together into any sort of coherent whole. Both are spectacles of a sort, each celebrating a particular carnaval.

The only difference I can see is that one is terrifying, the other gorgeous, true.

Balé Folclórico da Bahia, Merriam Theater, Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts, Feb. 17.