“Mano po” is a gesture of respect and gratitude. It starts with hands: the back of an elder’s fingers pressed gently to the forehead of the younger. KULARTS’s dance film, Man@ng is Deity, offers a “mano po” to the manongs and manangs of the Great Depression.

This generation composed “the first wave of cheap imported Pilipinx laborers who powered the ever-expanding needs of the developing United States empire.” While manongs have historically been depicted as the suave Filipino bachelors of the 1920s, the film reveals their history of organizing, resistance, and queer sociality.

The film unfolds in seven parts, paying homage to the legacy of the manongs. In the fields, they kick up dust and spar with eskrima sticks, practicing martial arts. They straighten their hats and march together, their actions swift, gliding with Astaire-like lilt down sunlit streets.

Their hands labor heavily: farm hands, hired hands. Cut, gather, tie, repeat. They punctuate—“WELGA!” pumping fists like iron pistons to the sky. At night, in the taxi dance hall, the manongs drink, play, and fight. Cajoling, exclaiming, casting dice, hands tip hats over knowing smiles.

Man@ng is

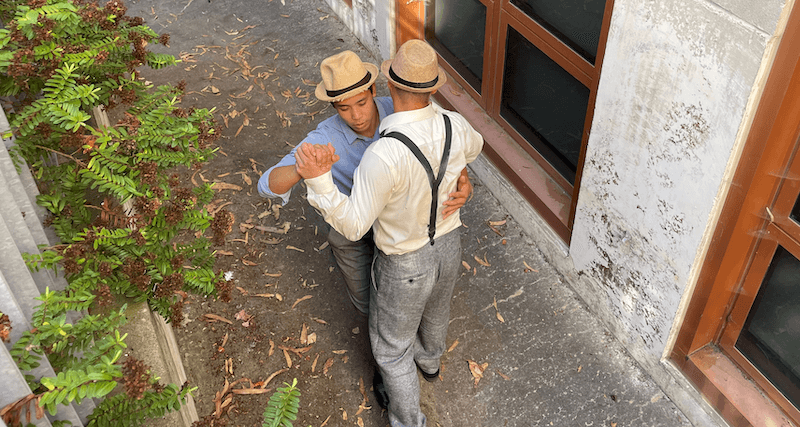

After the shiny exuberance of the taxi dance hall, “Benito and Antonio” surprises me, presenting a queer Filipino American relationship in the 1920s/’30s with a dreamy and artful eye. The duet is presented twice, first in proscenium and second in location: a leaf-strewn space between the buildings of a downtown district.

The men lift and partner each other, approaching, slowing, yet never stopping. They are cloudlike, drifting, while cement walls bookend their bodies. Viewed from above, two fedoras float down a narrow path, their wearers pressed cheek to cheek.

I appreciate the way this dance unfolds like weather: thunderheads and fog arrive but never stay. The secretive nature of this relationship does not seem to define it—the partners create their own clear sky, a floating world.

Deity

Buoyed by inner tides

Circularity and wavelike logic abound; despite the strictures of heteronormative relationships and hard agricultural labor, the dancers seem buoyed by inner tides and a deep connection to land. In “Laboring Bodies,” the manongs trace circles in the soil, mounds emptied on the stage in coffee-like hues. Informing their bodies: a retreat in Hawaii, where the dance artists learned to plant and weed on a Filipino-owned farm prior to filming.

Man@ng is Deity is an elegant gesture of respect: a tender hand, a tipped hat, a deep genuflection to this generation of lovers, laborers, and leaders of the 20th century.

In the final tableau, two men stand at the shore’s edge, trousers flapping in the wind. As credits roll, they step slowly forward, advancing side by side.

Man@ng is Deity, KULARTS, San Francisco, streaming on demand until February 28, 2022.