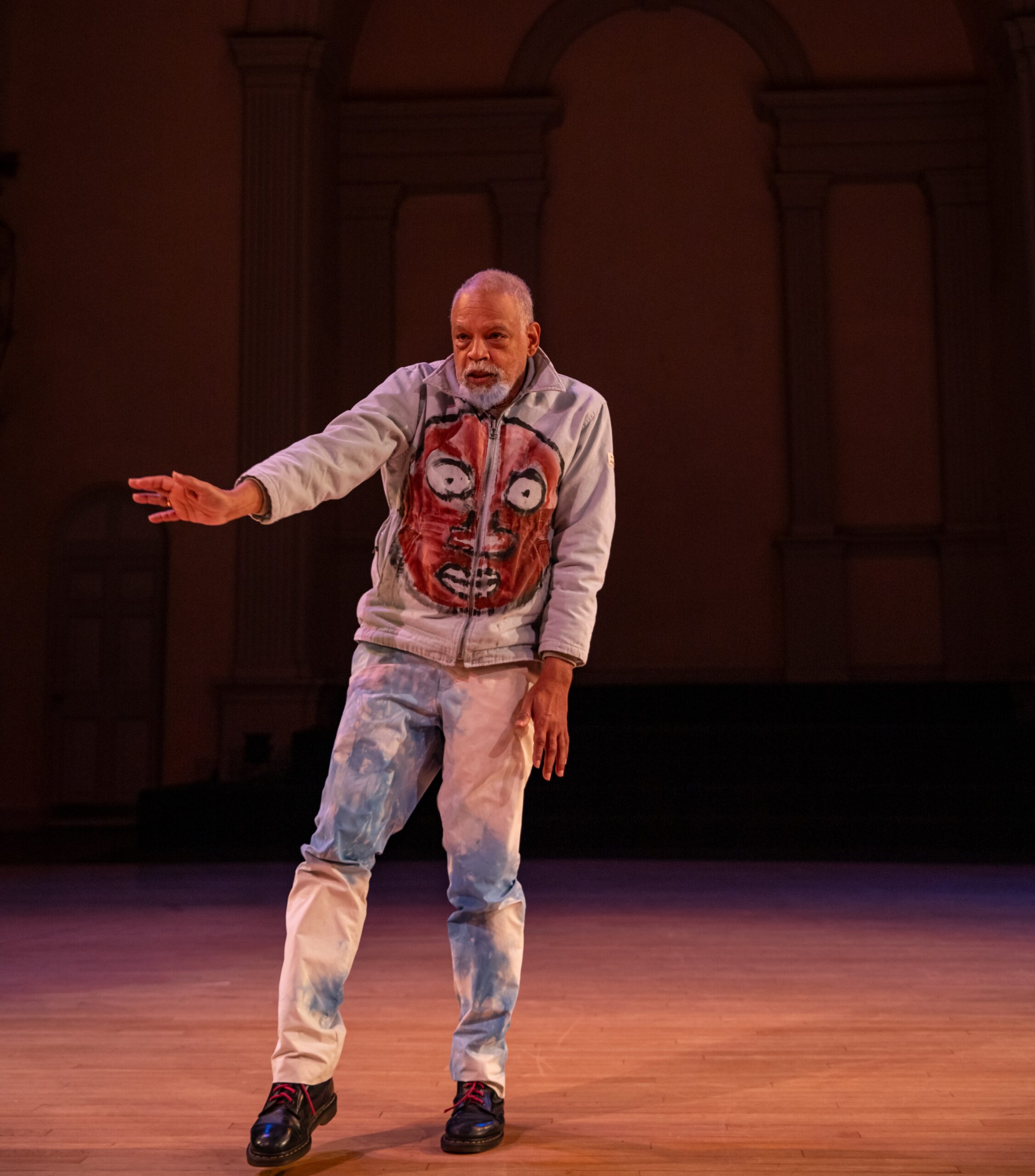

Six dancers scatter across the wooden floor, frozen in distinct poses: one kneels in a cat stretch, another’s arms resist the air, a body spirals, and another arches back like a cobra. Seated on a soft cushion against the side wall of the stage, I can clearly observe the dancers’ subtle eye blinks and the gentle rise and fall of their bellies as they breathe. Directly before me is Meghan Frederick, dressed in a cropped tank top adorned with yin-yang symbols and a short wrap skirt featuring an unmistakable American flag. As David Bowie’s rendition of the Beatles’ “Across the Universe” plays, I contemplate how the dancers’ movements, the music, and the costumes will interplay to reflect the concept of the “body as archive.”

My initial curiosity about After Yes stems from its ambitious program notes, which reference prominent critical theories, such as Michel Foucault’s disciplined body, André Lepecki’s body as archive, and José Munoz’s ephemera as evidence. The notes also position the show as a rejection of traditional meaning-making in Western theater and improvisation. With Frederick’s dramaturgical vision and the production’s bold theatrical claims in mind, I am curious to whom the performance says “Yes” and what history the bodies are re-enacting to become an archive.

After the other five dancers exit the stage, Frederick slowly extends her kneeling posture into distorted, grotesque movements. At times, her long leg sweeps across the floor, causing her flag-patterned skirt to ruffle, revealing glimmers of shiny blue underwear. As the song “The End of the World” plays melodiously, Frederick’s improvisation reaches its crescendo. She leaps across the floor, her swinging torso in rhythm with the song’s triple meter.

Following Frederick’s solo, two dancers return and mark out a rough three-square-foot space in a corner of the stage using tape. They resume their earlier gestures from the opening sequence, gradually evolving them into improvised movements. Despite negotiating within this confined space, their limbs continue to stretch fully, their disciplined bodies rising and falling alternately without conflict.

In the background of cheerful bird songs, the remaining dancers gradually re-enter the stage, expanding their initial gestures into individualized phrases, such as angular arm shifts, smooth floor work, or gestural alternations. As they move across the stage and interact with one another, their smiles and spontaneous movements signal the transition from solo work into a more cohesive group dynamic.

The performance concludes with an energized solo set to Britney Spears’ “Dancing Till the World Ends,” as the other dancers sit on stage as an audience. Frederick’s hour-long performance disrupts many traditional proscenium stage conventions, including the clear separation between audience and performer, the dancer’s obligation to create meaning, and the geometric precision often associated with group choreography. However, while the performance references Foucault and Lepecki, neither the movements themselves nor the added theatrical elements provide a compelling reenactment that effectively bridges the past and present, as one might expect from the concept of “body as archive.”

If I were to justify this lack of overt theoretical or historical linkage, I might invoke Muñoz’s idea that the ephemeral nature of live performance vanishes only at the moment, but endures in another form. Perhaps the connection between past and present is not in the performance’s explicit content but rather embedded in the dancers’ embodied sensitivities and the transient beauty of live performance.

After Yes, Meghan Frederick/Practice Project, Studio 34, Fringe Festival, Sept. 21, 22, and 29.

Homepage Image Description: Meghan Frederick in a kneeling, twisted pose, wearing a tank top covered in yin-yang symbols and a skirt patterned with the American flag, performing on a stage with abstract drawings taped to the wall behind.

Article Image Description: Three dancers in a performance space. The dancer, Esmeralda Luciano, lies on the floor while two others are standing and moving dynamically. Meghan Frederick, on the left, wears a yin-yang tank top and American flag shorts, while Ella-Gabe Mason on the right, dressed in a red sweater vest, raises an arm with a focused expression. The background features abstract drawings taped to the walls.