Haram, a one-woman dance theater film by Chelsey Fawcett starring Keena Herman, is an eye-catching and poignant part of Philadelphia Fringe Festival 2024’s Digital Fringe. A project that took years to build, it creates a single narrative out of multiple women’s stories. It touches on themes of female rites of passage, womanhood, the feminine divine, cross-cultural exchange, music, sensuality, sexualization, agency, exploitation, and power. If that seems like a lot, that’s because it was a packed 40 minutes.

Candace, played by Keena Herman, is a dancer at a shisha club somewhere in Canada. She starts the piece off as though on stage talking to the club’s audience. Almost immediately, a kind of flashback clues you into some dark events ahead. From there, she travels to Egypt and back, grows within her dance circle, and then spirals into darkness at the hands of the new club owner. Herman’s performance was careful and physical, culminating in a one-woman depiction of violence that left me on edge.

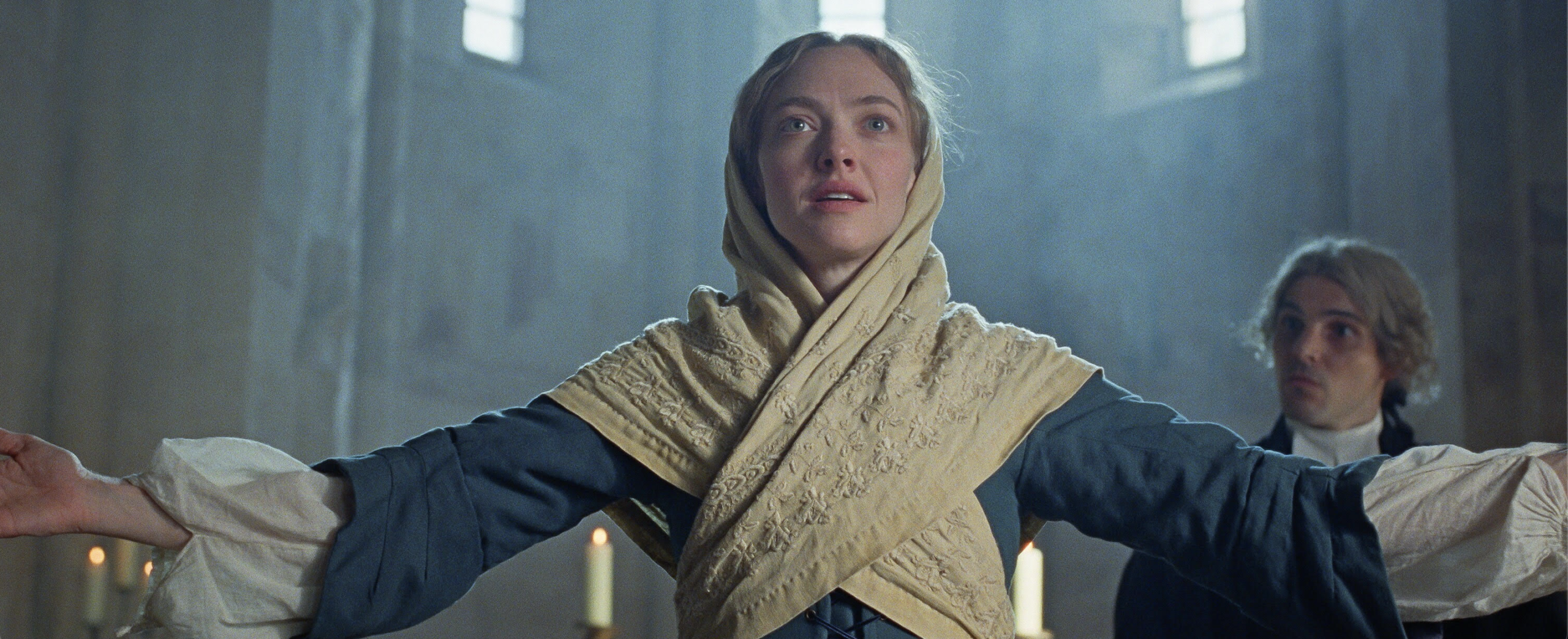

Haram is staged like a theater piece but filmed like a screendance. There is a set like a stage, twinkling lights, gauze, and pillows, with a great deal of camera work following Herman’s gestures, switching points of view, engaging with the material in a way an audience member can’t, sometimes framing her so tightly it was claustrophobic. Fawcett’s direction and the camera work seemed very clearly chosen at times; other times, the camera work seemed not forgotten but left alone, as though we needed to be put back in the club watching a woman on stage.

My only wish for this work was that there were more spaces for dance. Between a very short beginning and a demonstration of belly dance learning, and then a full-throttle angry deconstruction of the form later on, a long monologue left me needing more dance. The script speaks with such love for the form, but the work gives us so little of it in the end.

A few years ago I started colliding with men. That is to say, I started to refuse to step out of their way and began to have to physically withstand being walked into.

Why does this come to mind? At the end of this film, there’s no redemption, and, for me, the grim realization that in spite of my knowing better, I left the work questioning the women’s choices, not the abusers’, not the men’s. How deeply in our social structure is this ancient divine power of ours buried? What would it look like if these worlds collided? A woman’s power no longer being forced to step out of the way, or pushed out of the way? How long will it take to retrain ourselves to say, “he shouldn’t have done that,” and not, “she shouldn’t have been there?”

Haram, Chelsey Fawcett, Philadelphia Fringe Festival: Digital Fringe, September 1-30

Homepage Image Description: Yellow lights and gauzes of yellows and pinks set the stage. Seen from behind in silhouette, a belly dancer looks over her left shoulder and down. Her hands are raised slightly above her head.

Article Page Image Description: A black background and red arabic lettering in the middle to the left with the translation, haram, written underneath. On the right, a close up of a woman’s shoulders, neck, and the lower part of her face. There are dark smudges or bruises on her neck. In fine black lettering above these marks it reads, “You have no idea how much power I hold.”