Twenty years.

Twenty tons.

Three stories high.

Assembled with remnants of abandoned homes.

An ark was built in Newark, New Jersey.

Kea Tawana relocated from Japan to New Jersey where she would eventually assemble her ark, built from the remains of demolished, redlined buildings, gentrification fodder. Newark was a reminder of a familiar displacement; the tumultuous fracture in her childhood created by World War II, which had forced her family story into one of fatal goodbyes, immigration, and resettling.

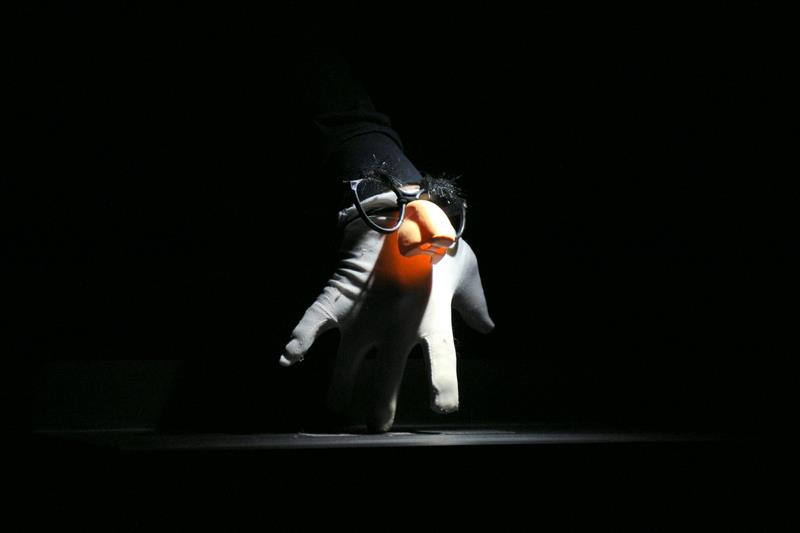

A giant black spider sits at the foot of the narrator’s stool near an even larger muskrat which is 90% skeleton with a mammalian head. A miniature cardboard model of a ship, a 1900s baby carriage, a giant coat and pants with no figure to fill it- intentional, if not quirky placements and curations that summon the inventive nature Kea demonstrated on her life’s journey. Kea and the Ark’s narrative of adversity contrasts with the charming wonderland Sebastienne Mundheim and collaborators create with puppetry, live soundscape, sculpture and shadow projection.

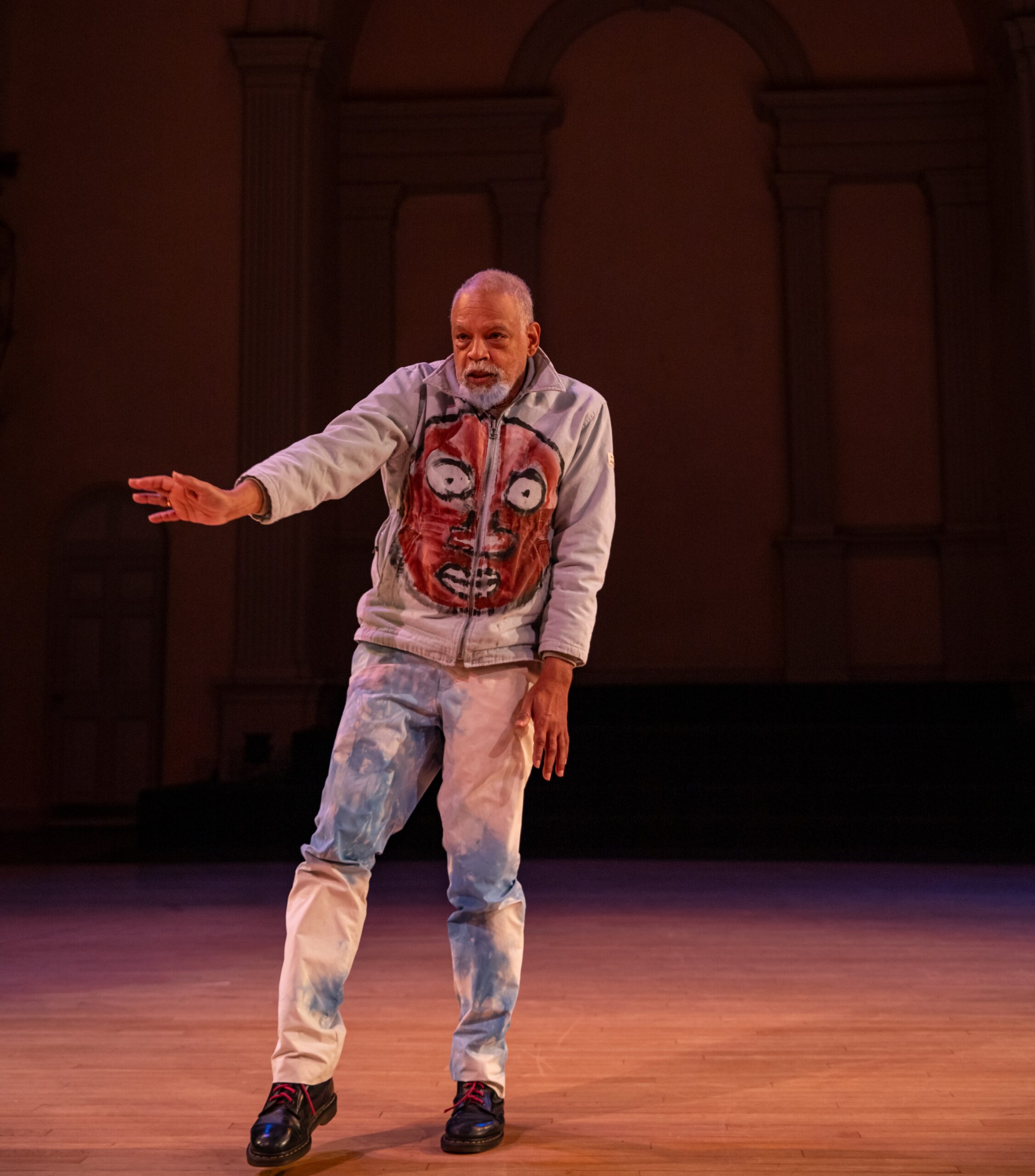

On stage, puppeteers Harlee Trautman, Payton Smith, and Candra Kennedy co-conspire to maneuver the puppets and props, seamlessly delivering the visual narrative. Their joint choreography eloquently animates the materials, giving each of the characters lifelike mannerisms. Smith, Trautman and Kennedy work together to make Kea’s puppet human; one person controlling the head, another positioning the legs and feet, the third working Kea’s arms and trunk. The intricate and sensitive synchrony to one another’s roles helps them transform puppet into person. The trio engages in careful guidance of one another and the tools that tell the story, listening, seeing, sensing, in time with the voiceover. Sculpted trees and their tangled branches intertwine with the limbs of the humans who carry them – they plant themselves beneath the roots momentarily lying down before the tree is forcibly plucked and replaced somewhere new. Grabbing cardboard toolbelts, puppeteers set up a sculpture of aJapanese style home. They are accompanied by Daniel de Jesus, who delivers the live soundscape via electric cello, synthesizers and vocals, and poetic storytelling read by Mundheim.

“And then the war began. Americans dropped bombs on Kea’s house.”

The story narrates Kea and her siblings’ migration to Newark; a turbulent and grief-stricken quest for stability and home.The family suffered several martyrs from the war along their migration journey before Kea and her brother made it to New Jersey safely. As Mundheim describes the unpredictable fate of travel by boat in an unruly ocean, Smith balances a tiny boat on the back of their hand. Using careful, full-bodied concentration, Smith embodies the potential for instability. Each step forward is a calculation that risks the possibility of imbalance. Her movement portrays the uncertainty of the anticipated arrival back to land referenced in the narration of Kea’s migration.

After some detail of Kea’s adjustment to life in her new home town, Mundheim narrates, “One day the developers said ‘we’re gonna fix this place up’…Puppeteers use a red fabric to measure a figure made of sticks that replicates the frame of a house. They model the redlining that often precedes gentrification and justifies the promise of economic enhancement in exchange for the livelihood of those discarded in the process. “And the buildings came down.” The stick house hangs from string which suspends the structure about waist height. Later, Kennedy, Smith and Trautman begin to disassemble it, then reconfigure the fragile frame into that of an ark, situating each part into place, piece by piece. The act represents Kea’s project. It symbolizes the resourcefulness and transformation exhibited through Kea’s journey and resettling, adding to the story’s themes of displacement and reclamation.

Kea and the Ark associates the imminent harm that war induces with the surreptitious violence of displacement caused by gentrification. Whether in the form of bombs or developers, by force or coercion, these acts of oppression are cut from the same cloth. Kea witnessed both, then built her ark out of collected items from the demolition. The narrative enlivens the essence of destruction and creation, artfully elevating the endearing moments and creative achievements that can exist in the seams of these inevitable cycles.

You can see upcoming showings of Kea and the Ark on March 1st and 2nd at the Don Evans Black Box Theatre in The College of New Jersey.

Kea and the Ark, Whitebox Theatre, Theatre Exile, Dec. 20-23.