Christy Funsch and Julie Mayo, choreographic instigators and artistic sounding boards for each other over thirty years, thank us for being there – “there” being Kestrels, a small studio in Brooklyn – and take their seats as the lights go out. As pure darkness overwhelms the windowless studio, a static-filled soundscore starts to blare. Over the course of the next twenty or so minutes, SetList unfolds –a searing slow burn of movement.

Funsch plays with notions of space and spacing as we see the four performers (Jordan Patt, Emily Hansel, Phoenicia Pettyjohn, and Cam Moreno) weave closer and further apart, breaking down the notion of “relationship” into a moment simply determined by space and time. The idea of the trio and the loner is crafted and deconstructed. Many times, Moreno repeats his limb-forward exploration on the outskirts of the playing space as Hansel, Patt, and Pettyjohn develop vignettes: Hansel carefully walks on an invisible tightrope held in place by the shaking fists of Pettyjohn and Patt, then quickly abandons the imagery halfway through; the three gently lop across the stage, arms held aloft like they’re holding large balloons as vaudevillian music spurts through the speakers; they face each other in a small circle as they perform fast, sharp gestural movements.

The four finally are facing each other, their sharp gestures are like straightening out wrinkles on shorts, with arms in the air followed by quick glances downwards, firm feet marking time — but this time with Moreno joining in. It’s a breath towards convergence that gets held temporarily, only to be released in the final image when Hansel pauses, hands like horse blinders for the eyes, as Pettyjohn, Patt, and Moreno crowd around them. They place and replace hands, renegotiating this relationship’s timbre, as Hansel’s eyes dart curiously around, never settling.

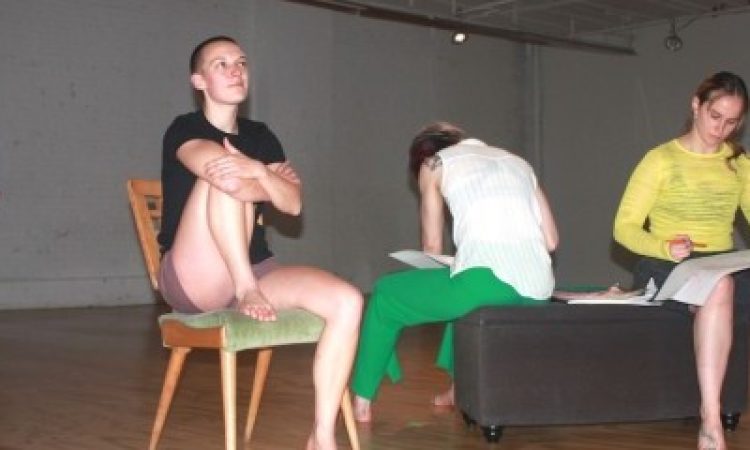

Mayo’s Waterfall begins abruptly: Julian Barnett, seated next to me in an aisle, begins to put sounds to gestures as he moves towards the far wall, jumping and kicking and blubbering all the way. He slices through the air, making quick turns then just as quickly rolling forward towards the ground; Mia Martelli approximates a response. She, too, carves space throughout the stage as she gurgles and flits across the floor, exploring the capabilities of matching and masking sound with movement. After a pause, Glenn Potter-Takata begins to groan and lean over, beginning his own solo investigation of sound and movement. He bear crawls backwards towards the audience, sticking an arm between two patrons as the opposite leg extends into the air. It’s exciting to see this relatively simple score playing out so differently across bodies, across time, and across space.

The three begin to fill the space together, sounding gone, their breath and the thud of feet the only noise in the room. As the dancers exhaust themselves with attitude turns and arms circling, they play with movements each has explored, mapping it onto their own bodies: a horse gallop looks different between Barnett and Potter-Takata as the latter focuses on the flapping of the folded hands behind the back, in a mimicry of a tail, whereas the former prioritizes speed and verticality of the leap; a deep plie run with exaggerated jazz hands becomes a recurring motif between all three performers. Space becomes negotiable as the dancers weave in and out of one another, eyes tracking other bodies for potential sites of repetition. “Blending, blend it,” shouts Barnett as he folds his hands together, fingers weaving through each other much like the three bodies on stage.

The three dancers, breathing together in a lull of movement, hold hands to form a circle. In a deep second position plie, they traverse the stage with stuttered steps, conjoining around a purple yoga block placed on the edge of the stage; they shift the block to a new home, stare at it, contemplating their relationship to this new spatial orientation. Martelli offers a thought: “the horse is blonde.” Barnett repeats, twice. A brief pause. Potter-Takata agrees– “the horse is blonde.” The lights dim.

Here, A Wife in Dance asks us to reflect on our own notions of how spatiality controls and contorts relationship-building. For thirty years Funsch and Mayo have been bound together by creativity, connection, and conversation. What does the space between them look like? These works weave and inform the other without even meaning to. Gestures and images (manipulation and touch/lack of, particularly) reverberate and repeat across the hour. We’re left with a sense of possibilities and the hope of connection.

Christy Funsch + Julie Mayo: A Wife in Dance, Kestrels (Brooklyn), March 21-22.