Image: Alexander Iziliaev

It’s opening night at the Academy of Music and the audience for Evening of Horror arrives in style: Gothic haute couture—velvet, lace, and dramatic silhouettes whispering of dark romance—peppers the theater. At first glance, Evening of Horror may seem like a seasonal thrill—a night to revel in the macabre—but beneath the surface lie two ballets that dare to explore the darkest corners of the human psyche: Agnes de Mille’s Fall River Legend, and Valley of Death, a world premiere by Philadelphia Ballet Artist in Residence, Juliano Nunes.

Through this double bill, Philadelphia Ballet shows that ballet, at its most daring, is about truth— allowing beauty to emerge from a full and unapologetic embrace of darkness, and finding the courage to face what lies beneath.

Fall River Legend recounts the infamous 1892 story of Lizzie Borden, accused—and later acquitted—of murdering her father and stepmother with an axe in Fall River, Massachusetts.The case became legend—blurring fact, myth, and moral panic in a town known for its lingering puritanical sensibilities.

Image: Alexander Iziliaev

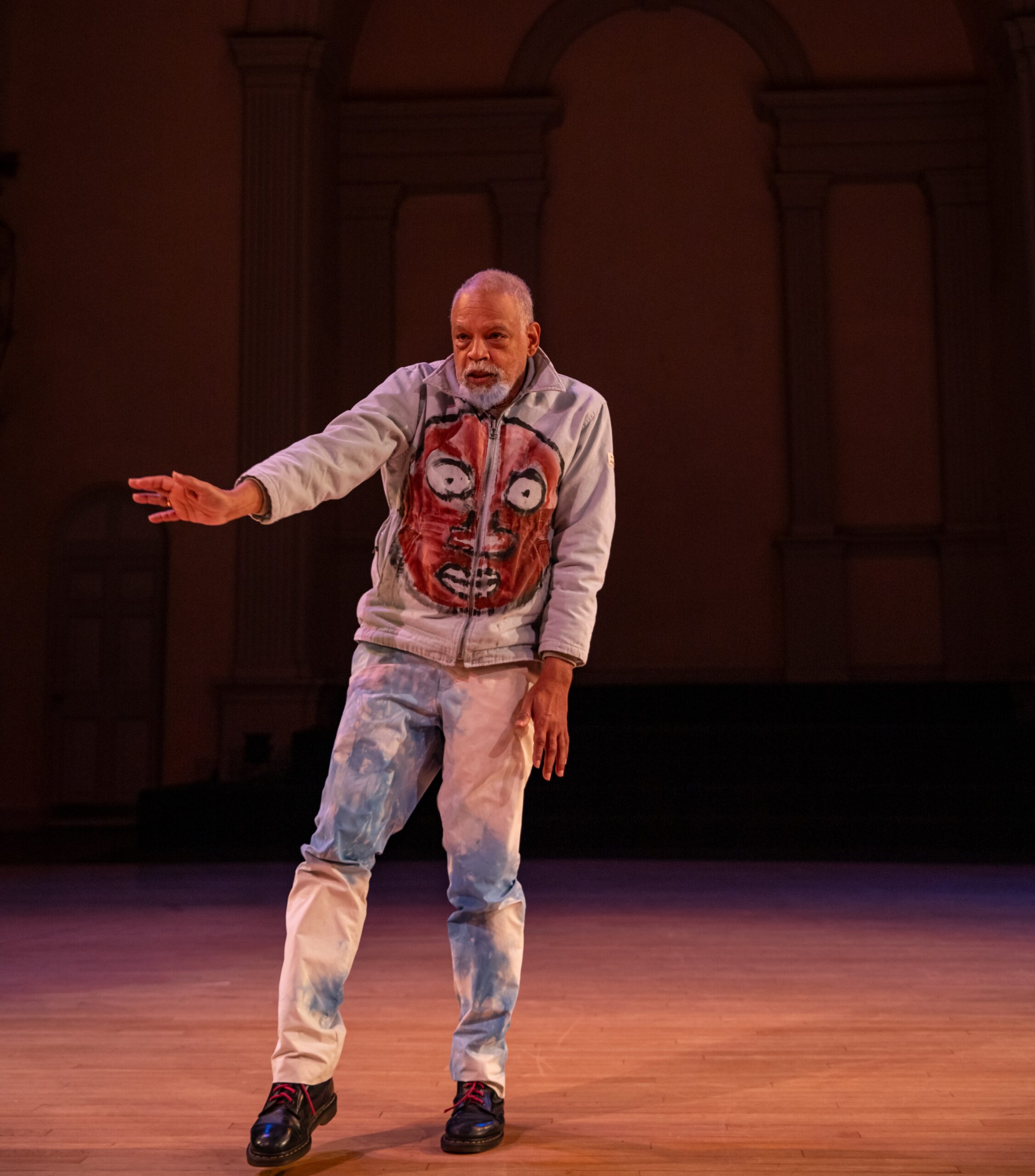

North Carolina native Sydney Dolan embodies Lizzie with a thousand-yard stare, balancing restraint, defiance, and a psychological unraveling, brought to life through the orchestra’s trembling strings and dissonant runs. Morton Gould’s score shapes the pacing as Lizzie stands before the gallows. Russell Ducker, a master of physical story telling, reads Lizzie’s haunting indictment.

In contrast to Lizzie’s descent into madness, the characters swirling around her embody a world of Christian restraint, modesty, and decorum—a brightness that feels both sincere and suffocating. Charles Askegard, as Father, holds a quiet authority through stillness and control, while Pau Pujol’s Pastor balances faith and discipline with the same physical piousness.

Fall River Legend moves with a doll-like folk quality—linear, precise, and just eerie enough to unsettle.

Lively square dances and uptempo waltzes take on a haunting edge, the corps de ballet’s buoyant energy heightening the suspense as Lucia Erickson’s young Lizzie drifts through memories of an idyllic, pastoral childhood.

Charlotte Erickson’s performance as the Mother offers fleeting moments of levity through softer, gentler lines, until a tender pas de deux with Lizzie’s father fractures upon her tragic collapse.

Gabriela Mesa embodies the stepmother, her gestures darkening with each harmonic shift. If her aim is to convince us that Borden’s stepmother was an unyielding ice queen, she succeeds, reveling in every villainous movement.

Enter Lizzie’s beautifully choreographed unraveling: grief embodied in her mother’s shawl, deepening as the Stepmother’s bone-chilling presence takes hold. Two pastoral rocking chairs—unnerving in any context—foreshadow Lizzie’s fall from grace.

Beatrice Jona Affron, the Louise and Alan Reed Music Director & Conductor, leads the Philadelphia Ballet’s Orchestra with cinematic tension and suspense—resonant, and edged with horror. Gould’s score shifts between light and dark, blending sweet, childlike passages with menacing undercurrents.

Dancers switch between theatrical stillness and sudden sharpness, their plastic smiles and rigid postures hinting at something sinister beneath the surface. The movement is unsettling, amplified further by Lizzie’s costume change: a dream sequence, a blood-spattered dress.

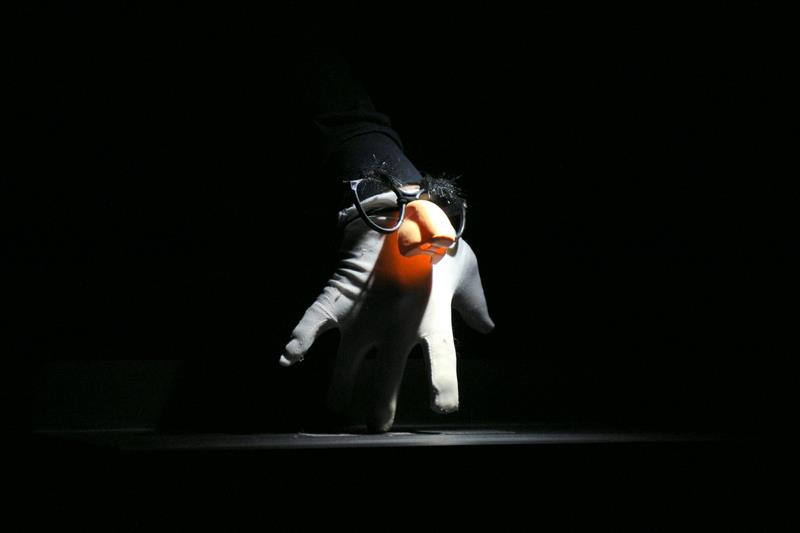

Cloaked, masked, and psychological, Juliano Nunes’s Valley of Death unfolds in rich imagery: chandeliers, lavishly draped fabrics, and a cast shrouded in secrets. Nunes once again establishes himself as a choreographic visionary capable of delving deep into the recesses of the human mind.

Image: Alexander Iziliaev

Costumes by Youssef Hotait, in collaboration with the Philadelphia Ballet costume department, fuse grotesque theatricality with haute couture —taffetas and pannier-inspired hip lines exaggerate silhouettes, while phantom-like masks elevate deliciously rich choreography.

The plot unfolds at a sumptuous masquerade ball. Principal dancer Zheng Liang embodies Oscar. Larger than life yet deeply human, Liang follows his recent turn as Don José in Carmen, moving through waves of both despair and transformation. Thays Golz shines as the merciless and sinister Agatha while Jacqueline Callahan’s Beth radiates emotional breadth; her expansive port de bras capturing the opulence of the moment.

The corps mirrors Oscar’s suffocating torment, while Agatha and her masked minions conjure a waltz of agony and transcendence. Virtuosic lifts, romantic partnering, rapid turns, and sweeping ensemble patterns explore love, deception, and the struggle between light and darkness.

Image: Alexander Iziliaev

By Part II of Valley of Death, everything changes. Dancing an underworld scene is always a risk—masked and costumed, the minions move in ghastly shapes, yet the corps delivers with nightmarish commitment.

For the second time in a week, the Academy watches Liang’s character die on stage—few do it with such conviction, proving tragedy can be beautiful and hauntingly human. In the end, he emerges irrevocably transformed, disappearing into a portal of light—a vivid reminder that from darkness, light and beauty can absolutely emerge.

Evening of Horror, Philadelphia Ballet, Academy of Music, October 16-19.