Reflections from the Philadelphia Museum of Dance

by Bridge, Coppersmith, Graham, Kingsford Smith, Kraus, Stoyanova

Our correspondents describe what stuck with them most during the massive Philadelphia Museum of Dance at the Barnes Museum.

Start with photographer JJ Tiziou’s animated recap of the day-long event to get a sense of the action here and then dive into words that capture the experience of six thINKingDANCE writers.

Strolling through the Solo Forest with Kalila Kingsford Smith

I follow streams of people first into a room where Sophie Sucré saunters in her green form-fitting gown. We lock eyes. As Sucré spins out of her dress, I wonder if the other audience members feel exposed watching this striptease in full daylight. I don’t. Her eye contact is engaging, intimate, and empowering.

Outside, I catch Lisa Kraus as she leans off balance, explaining how Trisha Brown asked her performers to test the limits of suspension. Her body and her voice is an embodied archive.

I spot Raphael Xavier frozen on his hands, feet in the air. Rolling over his forehead, he releases one hand, drawing a circle along the cracks in the concrete. He suspends the speed that typically accompanies breakdance, and I hold my breath, captivated by his detailed focus.

Between two trees, a collection of twelve-year-old students from Gwendolyn Bye Dance Center each await their turn in Lori Belilove’s staging of Isadora Duncan's Revolutionary Etude. Struck by these committed girls performing this powerful solo barefoot in the grass, I relish the idea that this is where Duncan wanted her dances: outside where one can reach, run, and dance without limits.

Rebecca Arends tries to go solo. Paul Lazar lectures. Miryam Coppersmith reports.

We're in the Annenberg Court when Paul Lazar grabs the mic. He launches into dense analytical text and the room clears out, except for a group clustered around a window. Behind the cool glass, Rebecca Arends demands our attention. Her precise movements punctuate the words of civil rights activists pouring from a small speaker nearby. She kneels with her hands crossed behind her back, paces the hallway, confronts us directly with her gaze. Lazar's voice (backed by a much better sound system) drowns out the activists' words in his Palace in Plunderland, adopted from Claire Bishop’s text. What is the use of this "alternative possibility for exhibiting dance performance" when the resulting effort is more people of color's voices drowned out by white lecturers?

A point of pride for Megan Bridge

My favorite thing about the Philadelphia Museum of Dance was the aptly and evocatively named “Solo Forest,” where multiple soloists, from Philadelphia and beyond, performed simultaneously at scattered locations throughout the Barnes campus. What struck me, with a shiver of pride, was that every single performer that I encountered from Philly looked their audience in the eye. They were humans, themselves, performing inside varied dancing personas. The one French dancer that I spent a significant amount of time with, while beautiful as a mover, held a frozen gaze that landed somewhere above my head in the middle distance. It was an afternoon that told me much about Philadelphia being a “city that loves you back.”

Zornitsa Stoyanova meets with the curators

Lois Welk, Simon Dove, and Manfred Fischbeck (three of eight curators) shared that the Philadelphia Museum of Dance at the Barnes was only possible because of the participation of French choreographer Boris Charmatz. Two years in the making and administered by Drexel University, the project created incredible partnerships between the Barnes Foundation, FringeArts, four local universities, and over 200 dancers from Philadelphia and its suburbs. The curators’ disclosure revealed that the European import was the only reason The Pew Center for the Arts and Heritage was interested in funding the day of dance.

So, what’s next? With “The Center” funding internationally famous artists, does it mean that Philadelphia will forever be activated only by guests? Could these newly established partnerships create a project together and diversify funding, so a similarly grand and exciting event could happen again? What would an authentic Philadelphia Museum of Dance look like without funders dictating curatorial process?

To truly support the incredible Philadelphia dance community, I hope future versions of the Philadelphia Museum of Dance, through keeping it local and honoring the living and past histories of our city, create an even more impactful and important event in the years to come.

Patricia Graham rides the tide.

The Philadelphia Museum of Dance put me in a mind of water as we flowed, pooled and collected along the spaces as spectators, participating in a fluid viewing experience. I was of a mood to completely ignore my program book and explore naively.

And so, finding myself pretty quickly entering the pool of interest around Lisa Kraus, very close to the front gate, I settled down there and once in, compulsively watched all of her sets. It was a deep dive into Kraus’ ocean of experience, which she carries for a generation and a movement in modern dance. Stillness, falling, folding, un-folding, jumps and turns - even a half-interested observer can be taken into the undertow of these waves, especially in this proximity.

I heard a colleague describing Kraus as holding an archive within her body. I would add that Kraus’ precise verbal analysis of this archive is fun and illuminating for the audience, but never detracts from our sensibilities. I feel the mysterious pull of the ocean when she moves.

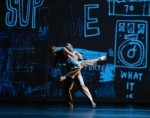

Lisa Kraus sees a Mass Movement

Boris Charmatz’s preferred number was 200 student performers for his dance 1973. The 115 or so who swept into the vast atrium space to execute a series of disconnected gestures still became an impressively seething mass, like a forest, or a school of fish, but each with its own will and direction—a human organism built of multiple human organisms. We have arms, legs, sight; we have the ability to run and plunge; we can feel each other. The space cleared and filled again, the tempo slowed or got raucous, the celebration of being and energy and physical capacity roared a proclamation: here we all are.

Philadelphia Museum of Dance, presented by Drexel Dance at the Barnes Museum. October 6.

By Kalila Kingsford Smith

November 14, 2018

.png)