The CINARS Biennale, an international performing arts festival and trade show in Montreal, ran from November 14 to 20, 2016. One thousand, five hundred and thirty-eight participants attending from 40 countries gathered to watch curated as well as “Off-CINARS” performances, to network, and to buy and sell shows.

At the exhibition hall, one of CINARS’ main features, agents and artists rent booths to exhibit their work to presenters who wander through the stalls, “shopping” for new work, collecting business cards, flyers, thumb drives, DVDs, press kits, and everything else you can imagine that might sell a show. Some countries’ and cities’ governments sponsor the cost of a booth and send delegations of artists to the conference, often covering airfare, lodging, and conference registration. This was not the case for any U.S. artists.

Beyond the booths, and between official CINARS showcases and Off-CINARS performances, there were more shows than anyone could attend.

I experienced the one official dance showcase at CINARS mostly as a political statement. Four companies performed over the course of two hours. During this time, 18 men and 2 women appeared on stage. This outpouring of testosterone was a visceral affront to my sensibilities as a feminist and as a female choreographer, especially when viewed in light of some of the numbers: the imbalance is not simply a coincidence of curation, but a systemic one.

Part One, Berceuse (Lullaby) by Panta Rei Danseteater (Canada/Norway)

Three men in dark suits deliver an onslaught of constant movement, either in isolation from each other or in outright competition. The movement is mostly in the upper body: far flung gestures, distally spoking arms. “Mwa-ha-ha-ha-ha….” laughs one performer, momentarily punctuating the live performance of pianist Sverre Indris Joner and Cellist Gustavo Tavares (both also men; no composer credit given). The laugh crystallizes the dance’s concept, fully acknowledged in the program: “Lullaby […] explores friendship, joshing, friction, needling, and aggressive behavior.” Ultimately, I read this work as the embodiment of the dominant media spectacle: white men’s ego-tripping and one-upmanship, with movement that is fast, aggressive, and competitive only for the sake of being so.

Part Two, Hasta Dónde…? by Compañía Sharon Fridman (Spain/Israel)

Two men enter the stage, one carrying the other upside down, sack-of-potatoes-style. When they part, the carried one performs a long solo that begins with staggering, walking on the outside blades of sickled feet. I have ample time to notice his low-crotch pants and part-mullet-part-undercut hairstyle, two aesthetic choices that seem to drive the movement at least as much as anything else that I can fix on. The floppy-scarecrow vibe grows tiresome quickly. While ultimately I find this work more aesthetically pleasing than the previous (the movement is derived from a somewhat somatic origin—contact improvisation), it frustrates me that the form is usurped to forward yet another aggressive, competitive agenda. Again, according to program notes, “It’s a struggle between two sides.”

Part Three, Moi&lesAutres by La Otra Orilla (Canada)

Finally, a woman (Caroline Planté) is on stage, and she is an excellent guitarist. Two men wield microphone booms like toreadors with their spears. Classic flamenco iconography is totally deconstructed (female soloist and choreographer Myriam Allard wears red tights and a plaid mini-dress; the two male performers wheel the guitarist, in a desk chair, around the stage). Allard’s presence is playful and direct. When she covers her face with a fan, her body assumes a puppet-like posture, knees poking out as if connected to marionette strings, pulled by the music’s regular pulse. When revealed, Allard’s gaze is regularly fixed on the audience: not challenging, but noticing us and smiling back as we watch her pull apart the classic flamenco form. Her male dancing partner is less remarkable to me, perhaps because my eyes have been starved for a feminine presence.

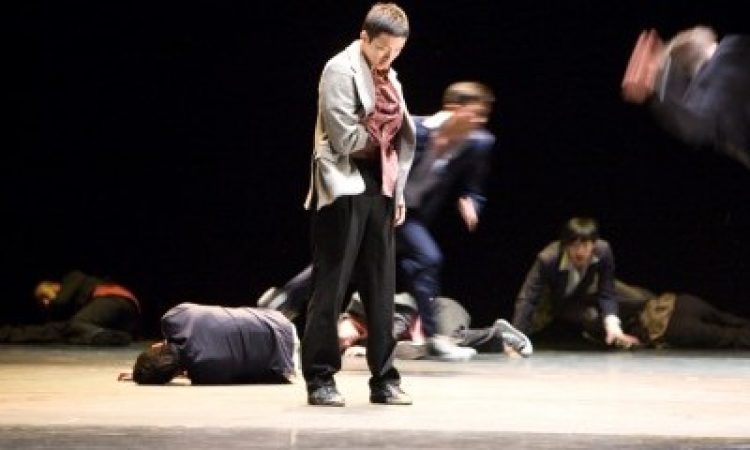

Part Four, No Comment by Laboratory Dance Project (South Korea)

A man begins onstage; we see his murky figure revealed gradually in dim lighting, his presence made audible as he repeatedly slaps himself on the chest. Another man falls repeatedly, but it’s not uncontrolled: more aggression, but this time characterized by grace. The two are joined by another, and another, and another, until there are nine men on stage. They cartwheel, skittering upside-down on their hands to traverse the space. Eventually, they accumulate in two diagonal lines that move forward gradually, the men performing a (literally) heart-pounding gesture. While the performers entered with dark suits and untucked shirts, each subsequent section is marked by a phase of further undress (removing blazers, unbuttoning shirts to reveal bare chests). I am self-aware of my (exoticizing, othering) admiration of this gorgeous group of Korean men who rush the downstage line, breaking past the proscenium and pouring out into the house as they exuberantly exit, punctuating the afternoon’s showcase with a final gush of testosterone that flows out of the theater on their heels.

CINARS International Exchange for the Performing Arts, November 14-16, 2016, Montreal, Quebec: multiple performances and venues; http://cinars.org/fr/biennale-2016/programmation/accueil.html