Cuba linda Pretty Cuba

Cuba hermosa Beautiful Cuba

Cuba linda Pretty Cuba

Siempre te recordaré I will always remember you

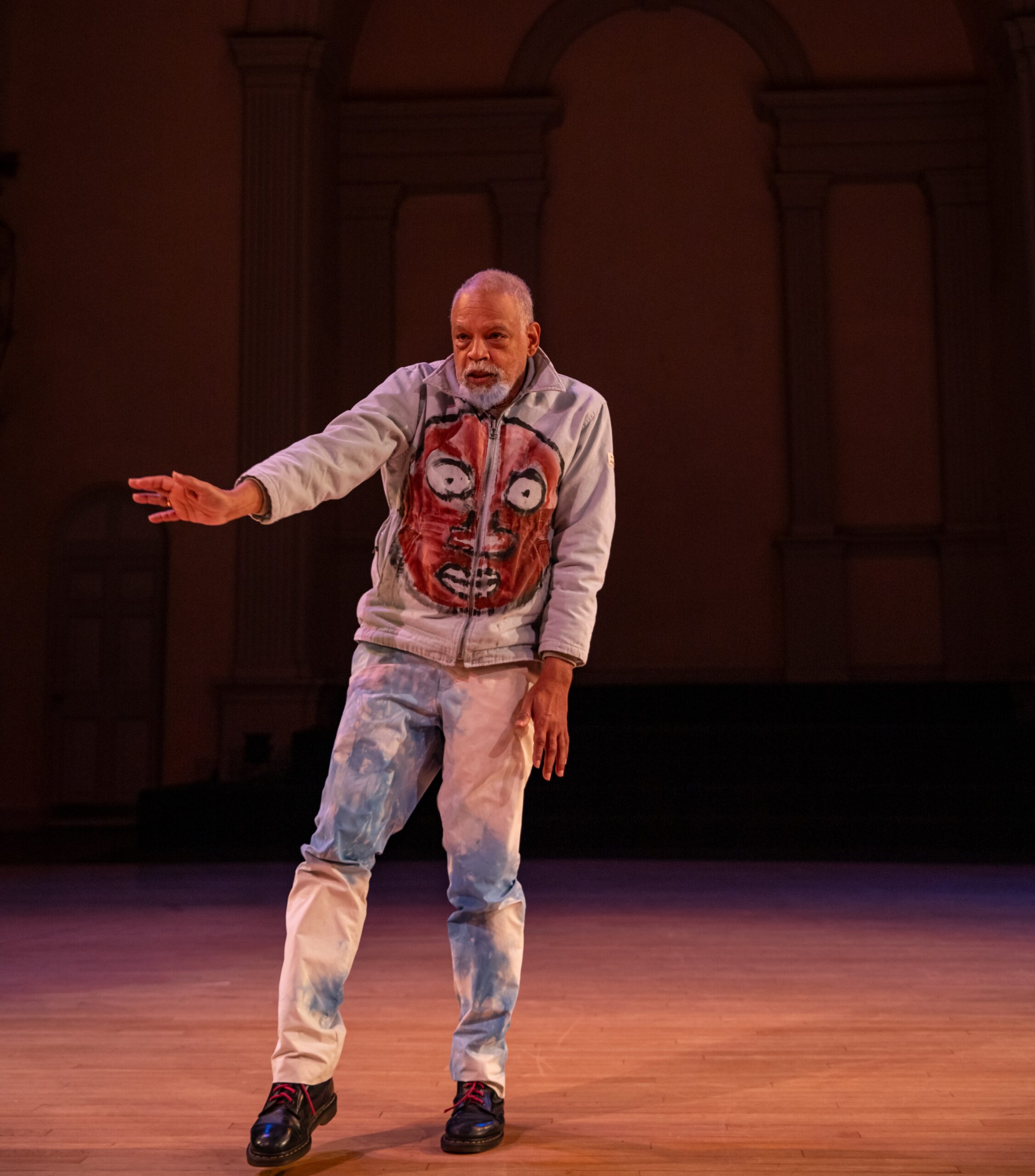

The world premiere of Malpaso Dance Company’s A Dancing Island, began with one dancer singing a slow and somber a capella version of “Cuba Linda” as the company slowly moved about the space. Choreographed by Osnel Delgado (co-founder, Artistic Director, and dancer), the piece transported the theater to the island of Cuba. Shifting in and out of son, conga, rumba, and mambo rhythms, the choreography masterfully mixed ensemble unison with partner dancing, attending to the music’s polyrhythm with accented hip, shoulder, and head isolations. At times the dancers held their arms in a fourth position. Rather than holding a presentational pose, however, the dancers energetically embraced the air as if moving in sync with an invisible partner.

Throughout the evening, I found myself contemplating, as tD’s Kalila Kingsford Smith did when she covered Malpaso in 2017, the legacy of modern and contemporary dance in Cuba. What is Cuban contemporary dance? And what is it about Malpaso’s movement and musicality that make the company distinctly Cuban? Dance scholar Elizabeth Schwall’s research addresses questions such as these in her analysis of Cuban modern dance during the country’s quinquenio gris (gray five years). Numerous works produced during this period of heavy censorship between 1971-1975 corporeally conveyed revolutionary ideas through boundary pushing performances that foregrounded the complexity of Cuban culture and identity*. Likewise, Malpaso’s repertoire showcased the dancers’ multifaceted embodied knowledge of the African diasporic elements of Cuban dance, classical ballet lines, and postmodern weight sharing.

The show’s opener, Aszure Barton’sIndomitable Waltz, was reproduced from 2016. Dressed in shades of black and gray, the dancers’ faces remained stern throughout the piece’s first section. Sharp turns and angular, staccato articulations of the limbs created a serious, almost militaristic, tone. Their mid-shin length black socks allowed them to slide across the stage. They performed intricate partnering work with a sense of silence and lightness, which allowed the rich string quartet sound score to envelope the space. Of the three pieces performed, Indomitable Waltz adhered the most to classical ballet and Graham traditions, but I was struck to also witness the way the dancers dropped their weight. Their lowered centers of gravity during a repeated bent-leg, hip-swaying walk with the hands on the hips and a contracted upper body kept the movement in conversation with African-diasporic elements of Cuban vernacular dance.

The second piece in the show, La Última Canción (2022), paid homage to the music of Cuban singer Bola de Nieve and featured moments of whimsy mixed with feelings of loss and uncertainty. Choreographed by Malpaso’s Associate Artistic Director, Daile Carrazana, the piece began in silence, setting the stage for a female dancer in a silky red jumpsuit to serve as the protagonist. Positioned a bit left of center, she slowly shifted her weight from one hip to the other. Caressing her left cheek with her right hand, she hinged at the hip before relaxing her torso over her legs. As the music began and more dancers emerged from the wings, the stage filled with shades of yellow, red, green, and deep purple in rich textures and silhouettes. The dancers played with the early twentieth century Cuban son sound score, at times accenting small pulses throughout their bodies to the sound of twinkling piano keys.

The three works Malpaso performed created a uniquely Cuban aesthetic that corporeally, sonically, and thematically foregrounded Cuban cultural pride. The company’s work seamlessly fuses polyrhythmic exactness, lowered centers of gravity, and sweeping circular arm motions of the African and Latin diasporas, with elongated balletic lines, modern dance philosophies of tension and release, and the energy of Latin jazz. After the performance, Malpaso received a standing ovation, and I left the theater with the clave rhythm reverberating through my body.

Malpaso Dance Company, Penn Live Arts, Zellerbach Theatre, October 6-7.

* Schwall, E. (2020). Cuban Modern Dance after Censorship: A Colorful Gray, 1971-1974. In R. Schneider, J. Ross, & S. Manning (Eds.), Futures of Dance Studies (pp. 303-320). University of Wisconsin Press.