On the final stop of their 2024 season national tour, the Limón Dance Company captivates Philadelphia audiences with four exceptional pieces. Two of these works, choreographed by founders Doris Humphrey and José Limón in the 1950s, offer rare glimpses into modern dance history. For me, as someone whose passion for American modern dance brought me to the United States, the performance evokes a kinesthetic familiarity that resonates deeply with me as a transnational dance practitioner.

The evening opens with Humphrey’s Two Ecstatic Themes (1931), a solo reconstructed from Labanotation and performed by Mariah Gravelin whose half-up, half-down hairstyle, and flowing white dress evoke the quintessential early 20th-century femininity central to Humphrey’s aesthetic. In the first movement, Circular Descent, Gravelin’s curved arm gestures and soft torso spirals flow seamlessly with her transitions from standing to kneeling. In Pointed Ascent, the second section, her movements take on an angular and fragmented quality, resembling the jerky motion of a distorted video. She remains at center stage throughout. Gravelin’s nuanced contrasts between the sections of fluidity and angularity harmonize beautifully with the polyphonic piano score by Nikolai Medtner and Gian Malipiero, achieving a simple and rich performance. With the absence of video footage, the written language of dance notation ensures Humphrey’s legacy endures, giving new generations the opportunity to experience the timeless beauty of her work.

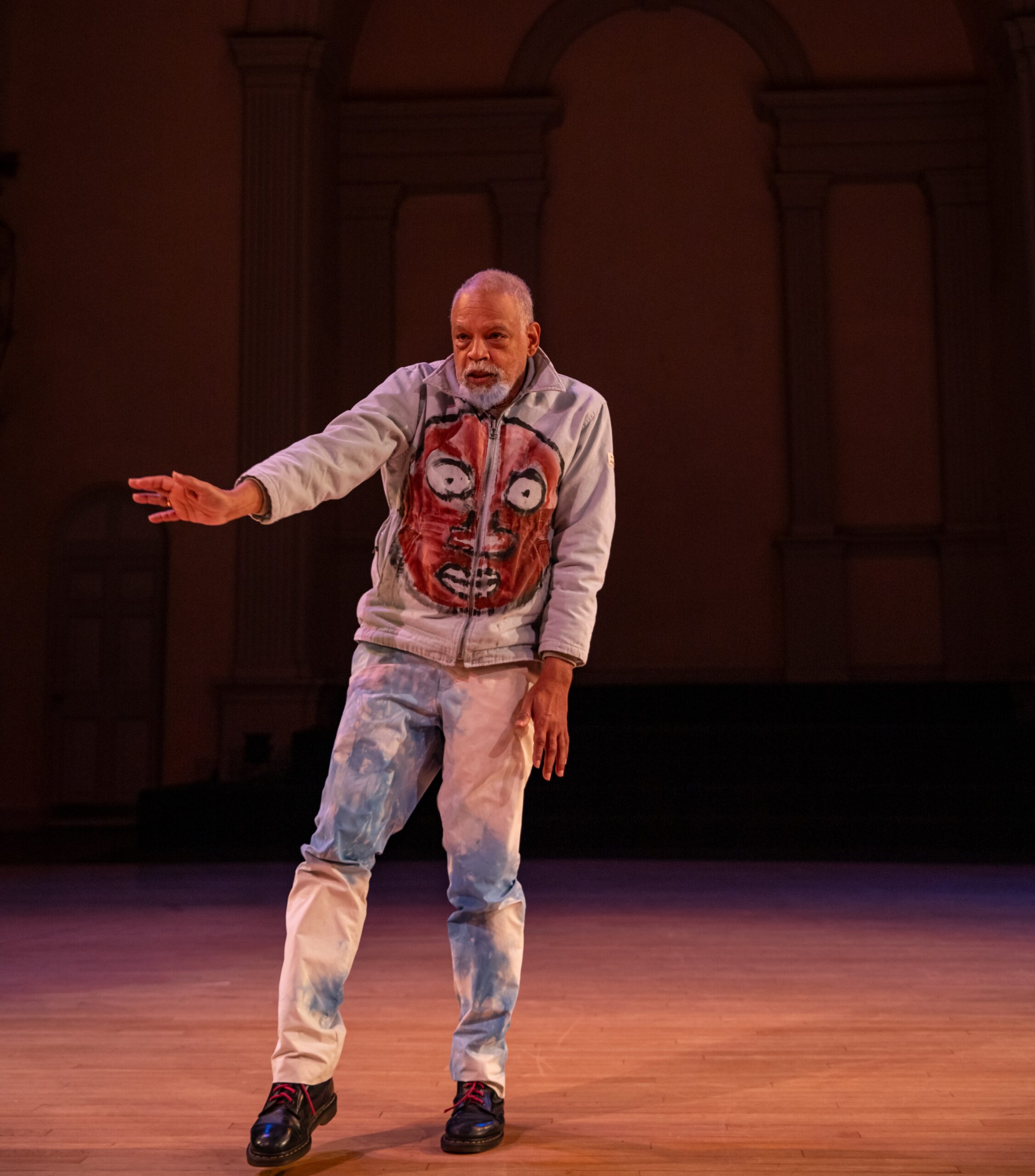

Created during the height of the anti-communist McCarthy era, Limón’s The Traitor (1954) is a story of betrayal inspired by the biblical story of Judas. In this Philadelphia restaging, a mixed-gender cast of eight dancers replaces the original all-male ensemble. The uneven arches in the background, reminiscent of the Roman Colosseum, enhance the dancers’ diverse use of space and provide a modernist abstraction to Limón’s narrative. Set to discordant brass music, the dancers move with suspicion, glancing around as they circle each other conspiratorially. The choreography conjures an atmosphere of mistrust through sharp entries and exits, groupings of duets and trios, and aggressive disruptions of the circle.

A white cloth becomes central to the storytelling: stretched between dancers, it mimics the table at the Last Supper; when draped over a performer, it sanctifies him as Jesus. Limón’s group lifts effectively emphasize the contrast in reactions to betrayal and reverence— Jesus ascends a “staircase” of dancers’ backs while the traitor is harshly lifted and dropped. These moments underscore the tension between power and vulnerability, central to Limón’s poignant choreography.

The evening lightens with Limón’s Scherzo (1955), a playful and rhythmic quartet performed by an all male ensemble. Clad in simple white pants, the dancers use their bodies as percussion instruments, beating their knees, hands, chests, and pelvises in rhythmic syncopation. The performers’ rapid, passionate foot stomps and rhythmic beats create a dialogue with the steady drum accompaniment. The choreography seamlessly combines technical jumps and turns with pedestrian walks and skips, as dancers exchange a hand drum in a lively game of rhythm and motion. The result is an exuberant celebration of movement and sound.

The final piece, The Quake that Held Them All (2024), choreographed by Kayla Farrish, draws inspiration from Limón’s Redes (1951) and El Grito (1952), exploring his Mexican heritage. Set on a smoky, dimly lit stage, dancers clad in olive and gray pants and sleeveless tops move with unified, cautious steps. The choreography is driven by shifting rhythms, from jazzy melodies to electric drum beats, and plays with recurring circular motifs. Stomps, quick torso bends, and dynamic group lifts evoke a ritualistic, almost mystic quality, enhanced by the dancers’ fluid exchanges between tentative and vigorous energy.

While the piece offers powerful and visually arresting moments, it suffers from overused contemporary dance conventions, such as repetitive running sequences and group formations that gather and scatter. These predictable patterns dilute the work’s originality, making it feel less distinct within the broader landscape of contemporary dance. Although I found the movement choices to be average, The Quake succeeds in delivering bursts of raw power and captivating rhythm.

The Limón Dance Company’s stunning performance highlights the enduring artistry of mid-20th-century modern dance choreography. While many contemporary works rely on spectacle, the elegance of Limón and Humphrey’s choreography reaffirms the value of “less is more.”

Limón Dance Company, Zellerbach Theatre, November 22 to 23, 2024.