In the world of Tere O’Connor, choreography becomes collage: the movement vocabulary seems assembled from multiple sources, from pieces that don’t quite fit together. Instead of coherent images drawn in clear lines by a single hand, O’Connor’s dances feel jagged, referential, complex. Here, flow is forsaken in favor of the unexpected.

For his recent program at New York Live Arts, O’Connor presented two pieces, Construct-a-Guy (1985) and The Lace (world premiere). Though created forty years apart, each illustrates his distinctive approach to creation, and both contain movement sequences that challenge predictability–of what we think a contemporary dance can (or should) do, of how a gesture or a somatic idea can resolve.

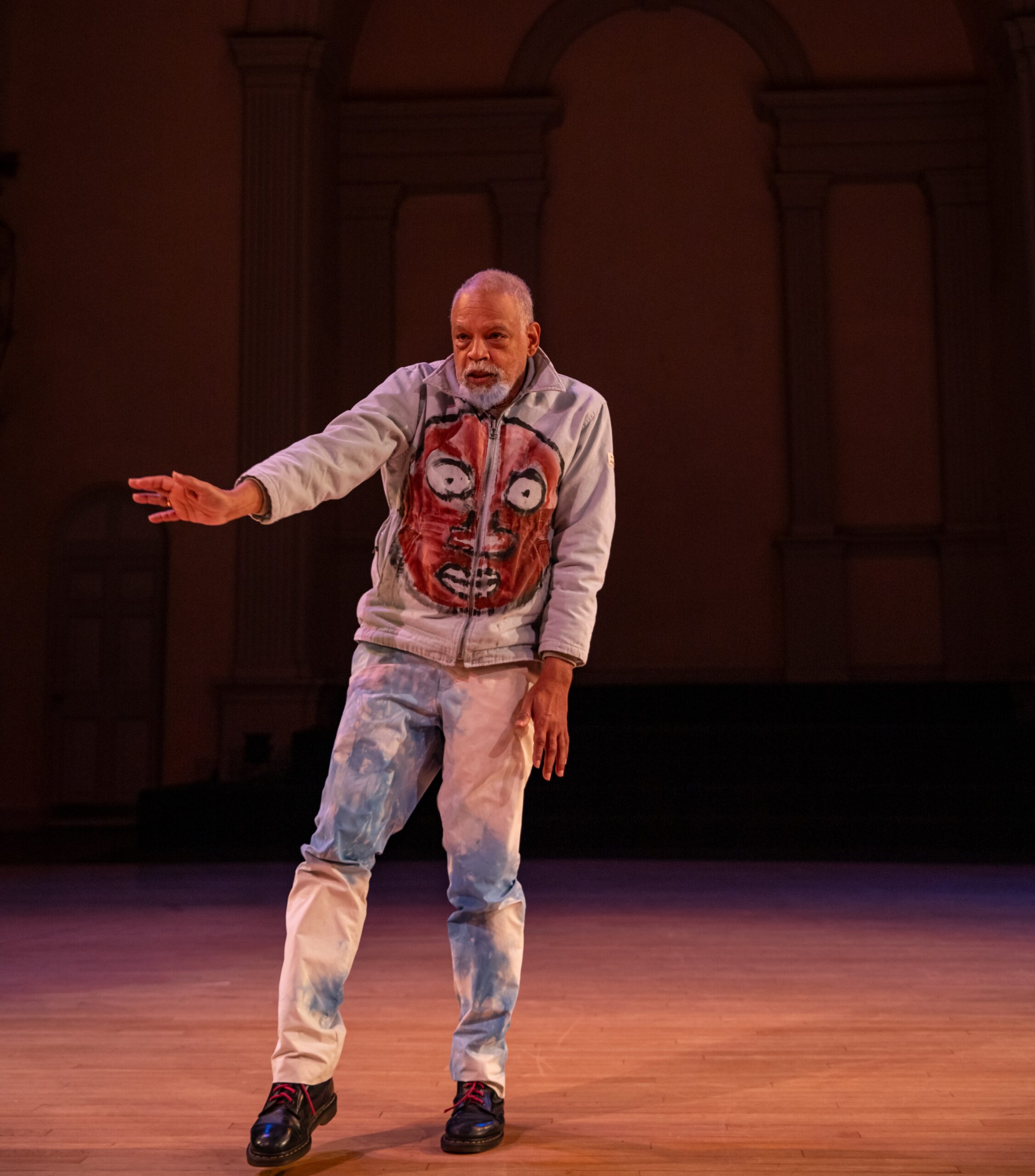

O’Connor’s restaging of his 1985 solo Construct-A-Guy has dancer Tim Bendernagel strolling, slipping, and subverting multiple states of motion. Over fifteen minutes, he inhabits a rich array of textures and qualities, performing each sequence with both technical precision and assured artistic flair. A simple, seemingly ordinary walk suddenly shifts into social dancing at an imaginary club, then bursts into a dynamic leap before landing in complete stillness in a new direction. Bendernagel primps and preens, gazes at the audience with disdain but then later with approval, his hands cover his face in shame then briefly rest on his hips while he waits for the next unspoken cue. Performed largely in silence–save for the occasional bite of rock music courtesy of Diane Martel (who passed away earlier this year)–each phrase of Construct-a-Guy is a puzzle piece pulled from a different box. The sequences are interrupted before ever reaching an identifiable completion, and transitions are often broken. These and other frictions are a large part of the pleasure of experiencing the piece.

During the brief interlude before his world premiere begins, O’Connor surprises the audience again, this time by coming onstage and spending a few moments explaining his work. “I want to pierce that cellophane between you and the dance,” he tells us, “to demystify what I’m doing.” He likens this ambition to the contextual information which accompanies a painting at a museum. “Sometimes, just a couple of sentences can really open up a work for people.” Why aren’t such explicit articulations of our work more frequent in dance?

Though often described as “experimental” or “avant-garde,” O’Connor emphasizes he never uses these terms to describe his work; he believes the terms are meaningless anachronisms from the twentieth century. He sees each of his dances as an “artifact of thought”–a series of decisions, impulses, and choices which arise from his “closeted mind.” He explains how Construct-a-Guy was created around the same time he was coming out of the closet, and thus the enactment of making became an ideological project. “Each one of my pieces are aspirational,” he says, “an oasis, a queer space of safety.” In choosing to put these two dances together, he found himself realizing that all of his ideas, all of his creative strategies were present from the very beginning.

We can see that, too, in The Lace (performed by Bendernagel, Leony Garcia, Gabriel Bruno Eng Gonzalez, Natalie Green, Aaron Loux, and Heather Oslon), especially after O’Connor’s eloquent description of his artistic origins and ambitions. There is a lot of playfulness between these dancers, these curious animals gazing at each other’s flesh inside the elegant costumes designed by Reid Bartelme and Harriet Jung, and even turning their eyes to us with an inviting sort of guile. I was struck at one point by how they used their arms and hands to arc through their entire torso with aching angularity to the sound of plucking strings; later, all six strut through the space like poised birds unable to soar. Visually framed with a lattice on either side of the stage by lighting designer Michael O’Connor, The Lace deepens the range of formal and thematic possibilities introduced in Construct-a-Guy: a woman dances solo while the others look on, but then the others shatter its conclusion by forming a quartet, or a duet. Physically, the dancers weave through stage-pictures that appear dramatic and then humorous; their limbs may clear the air around their bodies before hopping, sliding, or leaning into one another.

In his talk, O’Connor explains how much he loathes the words “abstract” or “non-sequitur” to describe his choreographic language, and after seeing this double-bill I can better understand why. Such descriptors imply something general, untethered to a real person making actual choices with intention in space and time. Seeing Construct-a-Guy and The Lace together in the same evening, especially with O’Connor’s comments in the middle, feels like visiting someone else’s personal utopia. The landscapes of both are not intended to depict anything in the so-called “real world,” but instead offer a lingering glimpse inside the workings of an inventive mind.

Tere O’Connor, Construct-A-Guy (1984)/The Lace (World Premiere). New York Live Arts, Dec. 3-6 & 10-13, 2025.