I’m often caught having that nostalgic conversation about storytelling—the one about the loss of linguistic nuance, the dilution of descriptive power, and the way attention frays as technology accelerates. It’s a soapbox I stand on willingly. I believe, maybe stubbornly, that we can reconcile ourselves to one another and begin to create real change and reconnection in the world if we return to the practice of storytelling—and by extension, the deep practice of listening. Or, in the case of physical theater, an attentive seeing.

PhysFestNYC, an all-things physical theater festival now in its third winter offering, presented a triple-bill evening at the Susan Adler Center for the Arts that didn’t disappoint my soapbox self. The featured three works in progress were Leila Ghaznavi’s Beyond the Light, Danielle Strader’s Monologue Duets, and Edu Diaz’s PETRUS. Each piece was imbued with a quality of physical presence that uplifted the storytelling and generated a range of audience responses: crackles of laughter, puzzled faces, quiet pockets of awe, and subtle head nods as we followed along with these mostly unspoken conversations. After the show, I overheard a cast member mentioning that they had added a scene at the last minute. I didn’t catch what or where—but that, too, felt like part of the evening: process still warm, still breathing.

Ghaznavi’s Beyond the Light, a series of episodic stories about love told through multiple forms of puppetry, began quietly—mesmerizing, like watching lightning bugs on a summer evening. A cast of puppeteers dressed in black bodysuits, faces covered, maneuvered blinking lights and delicate forms. You see them clearly, yet instinctively understand they are supports, not subjects. Some puppets shift and rearrange themselves; others are created from the performers’ own hands, dressed in gloves and eyeglasses. At moments, the black bodysuits are peeled away to reveal two human dancing characters in white, their bodies stark and luminous against the surrounding darkness.

The opening imagery suggests a primordial being splitting in two, a twin flame sent out into the world to be searched for. What follows is a series of scenes—some funny, some tender, some blending dancing humans with their puppet dates—that explore the ways we look for love, and eventually, what it might mean to find it. The pacing and flow of the sections are expertly crafted; I was never left wondering what something meant or where a thread was taking me. Everything was so clearly embodied, rendering words unnecessary. The sound design was the only disappointing element. The piece was described as a response to poetry by Walt Whitman and Rumi, yet that poetry and its language were absent, and I found myself either missing it, or maybe not needing to know that was the root of the artists’ exploration.

Strader’s Monologue Duets offered a very different atmosphere. Lights up. No theatrical artifice. A simple row of dancers and musicians upstage, taking turns stepping forward in pairs for short duets. Some pairings appeared fully merged, playful, as if inhabiting a shared internal logic. Others felt set or repeated, not as yet internalized. The range of instruments was wide, but the range of movement styles was noticeably narrower, which raised questions for me about how the pairings were determined and why.

Each new pairing was initially a delight—the constant switch-up of sounds and performers kept things fresh—but the transitions between duets halted the momentum, inviting applause that broke the flow. I found myself curious about the underlying form and process, which didn’t yet feel evident in the work. I suspect that if the transitions could become more fluid the piece could sink more deeply into its own playfulness.

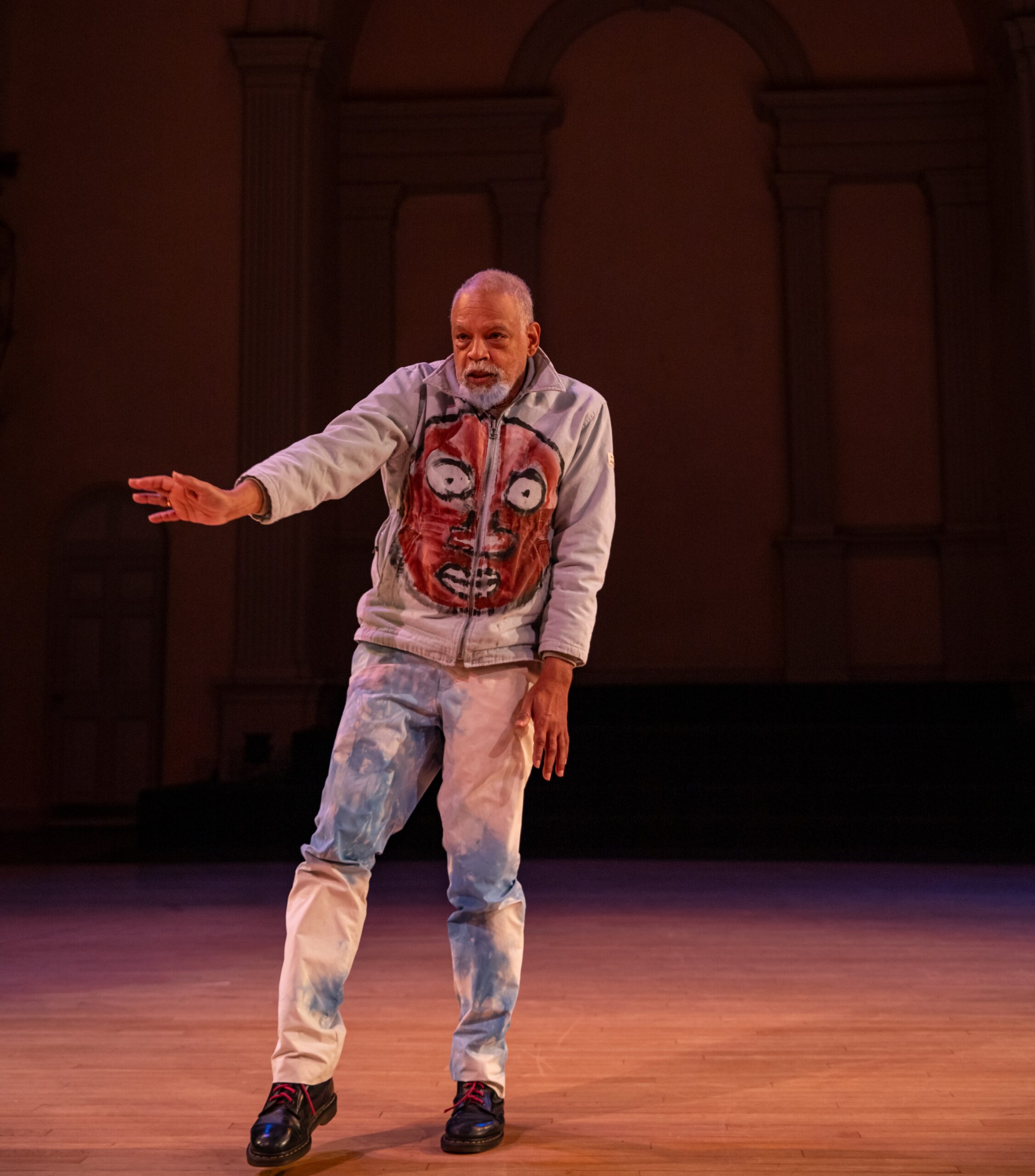

Then came PETRUS. Enter actor Edu Diaz in drag as Queen Catherine de Medici, galloping onstage in an explosive opening moment of mime and physical theater. The Queen exclaims to us, “I love the people,” —and we laugh immediately. Stage left, a window becomes a shadow-puppet theater where elements of the story on stage are illustrated. Diaz unhesitatingly destroys the fourth wall, teasing us into applause, into agreement, into complicity. An Iphone strapped to her forearm becomes both cue system and comedic device as she jokes about finding the next sound.

With nothing but a drag queen character, a phone, and wildly silly shadow puppetry, Diaz creates a layered theatrical infomercial. Is this the show? Is it a show about a show the Queen performs that we never see? Is it an advertisement for something fictional inside the thing we’re watching? The layercake accumulates beneath the outrageous persona and impeccable costuming, and the structure is clever enough that it leaves you wanting more.

What struck me across all three pieces was the way stories lived in minute bodily details: a hand puppet’s shy gesture, a fleeting glance between musician and dancer, the Queen’s expectant eyebrows. We don’t always need to paint large pictures. Sometimes the work and the joy is in attending to the intimate humanness of our tellers.

Puppets have been teaching us since we were sitting on the carpet in front of Sesame Street, or the first time we encountered a Bread and Puppet show. Daniel Tiger taught us about our feelings. Mr. Roger’s King Friday was always right. There’s a nostalgia in puppetry—a whimsical unrealism, the way you accept a character as fully real even while you can see the strings attached to their arms. Inside this form is enormous room to spin yarns, craft tall tales, push toward the truth, and gather people together—maybe to fight fascism, maybe just to laugh and love for a moment. The combination of dancing and smart, moving bodies with this form gives us emotional permission: to feel deeply without being precious, to grieve and giggle in the same breath.

Info Line: PhysFest Presents: Early Drafts Night 1 – Your Queen Presents: PETRUS (A Spectacle in Progress) // Monologue Duets // Beyond the Light!, January 12, Stella Adler Center for the Arts, NYC