Brian Golden is busy, or as he puts it, “constantly in creation.” He is a bi-coastal choreographer and movement director based in Los Angeles and New York, currently finishing his MFA in Choreography at CalArts. Golden builds intimate, playful, and deeply human choreographies that draw on his identity as Disabled and his experiences navigating Dyspraxia and Auditory Processing Disorder, exploring themes of belonging, neurodivergence, and the joy of being human.

Golden recently took part in a five-day residency at Dance Lab NY’s Disability Led Lab, directed by Jerron Herman, where he developed new choreographic explorations with a cast of twelve dancers. At the culmination of his Lab, Golden invited me, along with a small group of local artists and friends, to an informal sharing of the work-in-progress in Dance Lab’s midtown studios.

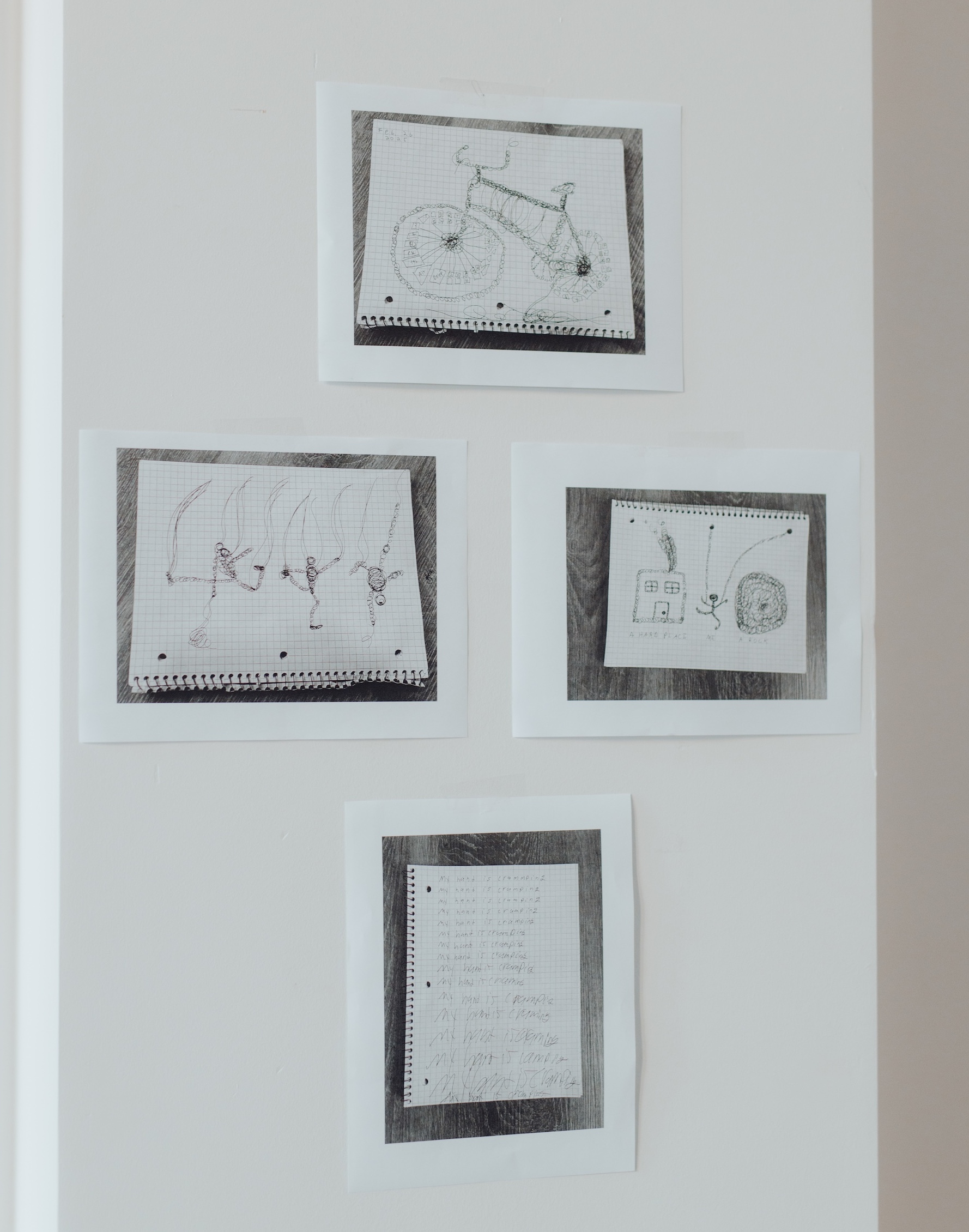

The bright, warm, studio space feels like a portal to another world—one far away from the 15 degree temperatures outside. Brian floats through the room, welcoming and encouraging us to check out a nearby table filled with sketches and poems created by Golden that served as a launching pad for Golden’s Lab residency. After exploring poems inspired by speech therapy sessions and sketches that reimagine shoelaces as a bicycle, I settle into one of the nearby seats. As Golden transitions us into the more formal portion of his presentation, he encourages us to laugh. And I did—almost immediately. As the dancers enter the space snapping their fingers, the rhythm quickly grows into a full song thanking the Dance Lab team—thank you to Josh, Jason, Jerron, and…Courtney!— while playfully poking fun at the Wi-Fi password, which, as the studios are housed within the Paul Taylor Dance Company facilities, is (of course) “Esplanade.”

Alt Text: Four sketches are arranged in a diamond formation on a white table. From top to bottom, the photographs depict: a bicycle made of shoelaces; abstract dancing bodies flinging long shoelace-like objects into the air; a building, dancer, and dark portal; a poem, with words filling the entire page.

Following his Dance Lab residency, I chatted with Golden about his experience creating this work, his overarching choreographic philosophy, and the playful curiosity his choreography invokes. Regarding his invitation to laugh during his sharing at Dance Lab, Golden says, “Sometimes I feel the audience wants to be on their best behavior…But, because it was a showing, and it was still very new, I felt I needed to say, by the way, you can laugh.” Golden continues, “I think humor creates access. It lowers the stakes and invites people into the room. It kind of drops the guard, but also draws the viewers in. It’s physical, it’s breath, rhythm, and release.”

Humor and play guide the audience through the tougher moments. Golden’s work pulls us in and reminds us that it’s okay to laugh, but it’s also okay to cry. This feels most evident during a section of Golden’s Dance Lab NY sharing, where the dancers burst into an energetic performance of the Cha Cha Slide, fully supported by the iconic instructional track by DJ Casper and exaggerated smiling faces. However, the lighthearted playfulness morphs into a tender exploration of Dyspraxia and Auditory Processing Disorder as the musical track begins to glitch, repeat, stutter, and fracture. Right foot, let’s stomp… Right foot, let’s stomp… Right foot, let’s stomp—the track shifts, transforms, and skips, stumbling over itself again and again. Speaking to the connection with his own embodied experience, Golden says, “I remember learning to skip. I could only skip on the right side. I couldn’t understand the cross-lateral coordination.” Despite remixing by composer Grant Johnson, the legibility of the pop-culture phenomenon remains, leaving both audience members and performers lingering in the uncanny valley between recognition and confusion—exactly where Golden wants us to be.

Throughout the work, props come alive as their own distinct characters—a hallmark of Golden’s work, which he credits to CalArts Professor Janie Geiser. “I’ve always worked with objects such as lipstick, beach towels, mannequin face masks…But I took [Janie Geiser]’s class at CalArts…called Material Performance. It’s on puppets, statues, and monuments, and it changed my life… It feels like the first time I had a professor outside of the medium of dance that saw me,” Golden says. “Thinking about…things that perform that are not alive… [Geiser] helped me understand these objects can carry agency, memory, and emotional charge just as powerfully as the human body.”

In his sharing at Dance Lab, Golden and his dancers use toilet plungers not just as props, but also as co-performers in the work. Citing Julia Kristeva’s notion of abjection, Golden notes, “[the] plunger is associated with waste, mess, and malfunction. It’s something you’re supposed to use quickly and put away.” In Golden’s work, the plunger becomes a metaphor for disability: “By [using the plungers] on stage, it allows me to surface those feelings of shame, care, [and] discomfort, especially in relation to disability…[and] how my mind feels.” On his lived experience, Golden notes, “My thoughts feel messy and backed up and overlapping…the plunger becomes a desire to unclog, to drain, to make sense of internal noise.”

Alt Text: A dancer wearing orange pants and a khaki-colored striped shirt leans back in a lunge. Their face is covered by a tousled black wig affixed to a toilet plunger, which they fling overhead.

During his summer residency at the Dance Gallery Festival at Catskill Art Space, Golden explored themes of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” and neurodivergence, transforming Poe’s raven into inflatable pink flamingoes: “It kind of got into body horror, but it’s a pink inflatable flamingo, so it wasn’t scary at all,” Golden says. As flamingoes are folded and contorted by the dancers, they coalesce as a human body being puppeted by the performers. “Kids [in the audience] really liked it because they were like, ‘the pink monster is so cool,’ similar to how we had the plunger monster,” Golden notes, referring to a moment in his Dance Lab work where the dancers used individual plungers donning messy brunette wigs and flashlights-as-eyes to transform into one large moving figure. Golden credits these explorations to his collaborative work with Josh Oberlander, a New York-based production designer.

Alt Text: Four dancers wearing black clothing assemble inflatable pink flamingoes to resemble a human body: head, torso, arms, and legs. The dancer on the left squats, two dancers behind the flamingo sculpture kneel, and the right-most dancer stands, gently affixing the flamingo’s “head.”

With Brian Golden approaching the end of his graduate studies, I was curious about his future plans. “I’ve gotten these really amazing residencies, but then it’s [like], where do I go from here?…I’m also wanting to build a long-term disability-led practice. There’s always more to learn, and that’s also what I love about it… accessibility is about the people in the room. It can’t be a one-size-fits-all.” In staying with that openness, where humor, rigor, access, and curiosity coexist, Golden’s work ultimately asks us not to resolve complexity, but to linger in it.

Rachel Repinz in Conversation with Brian Golden, Zoom, January 24, 2026.