In a quest to reach new audiences for performing arts in Philadelphia, Theatre Philadelphia and thINKingDANCE are joining forces and exploring how dance writing and discourse can provide new perspectives on theatre. Beginning May 2018, tD writers will be lending their varied backgrounds, interests, and approaches to criticism to professional works of theatre in Philadelphia. Let us know what you think in the comments!

In the early nineteenth century, melodrama threatened to push Shakespeare off U.S. stages. It muscled its musical-movement mélange onto American stages with all the Gothic horror and emotional manipulation that the stars and stock companies of the young nation could muster. It’s never left. Twentieth-century silent films grasped the power of movement and music to direct audiences’ attention and sentiment; later, the mid-day soap operas that glued housewives to TV screens kept the form vibrant. Animations, too, have depended on melodramatic elements to carry out their easy-to-read plots, transparent characterizations, and perplexities—all resolved at play’s end.

But “straight” drama, theatrical realism, and other trends came to dominate U.S. stages since melodrama’s nineteenth-century hey-day, so when Philadelphia Artists’ Collective chose to attempt recreating an old-style melodrama, my interest was piqued. Maria Marten, or, The Murder in the Red Barn is not among the hundreds of once much-presented plays of the genre; rather, according to director Charlotte Northeast’s program note, it was possibly “written by a group of theatre makers having so much fun, they couldn’t decide on an author so they magnanimously attributed it to Anonymous.” I wondered if that group was these very actors. The play, set in Polestead and London, England, in 1827, draws together “the sublimely ridiculous,” “sensationalism,” and “the eternal triumph of the white guy” (which the program note claims PAC’s production has subverted).

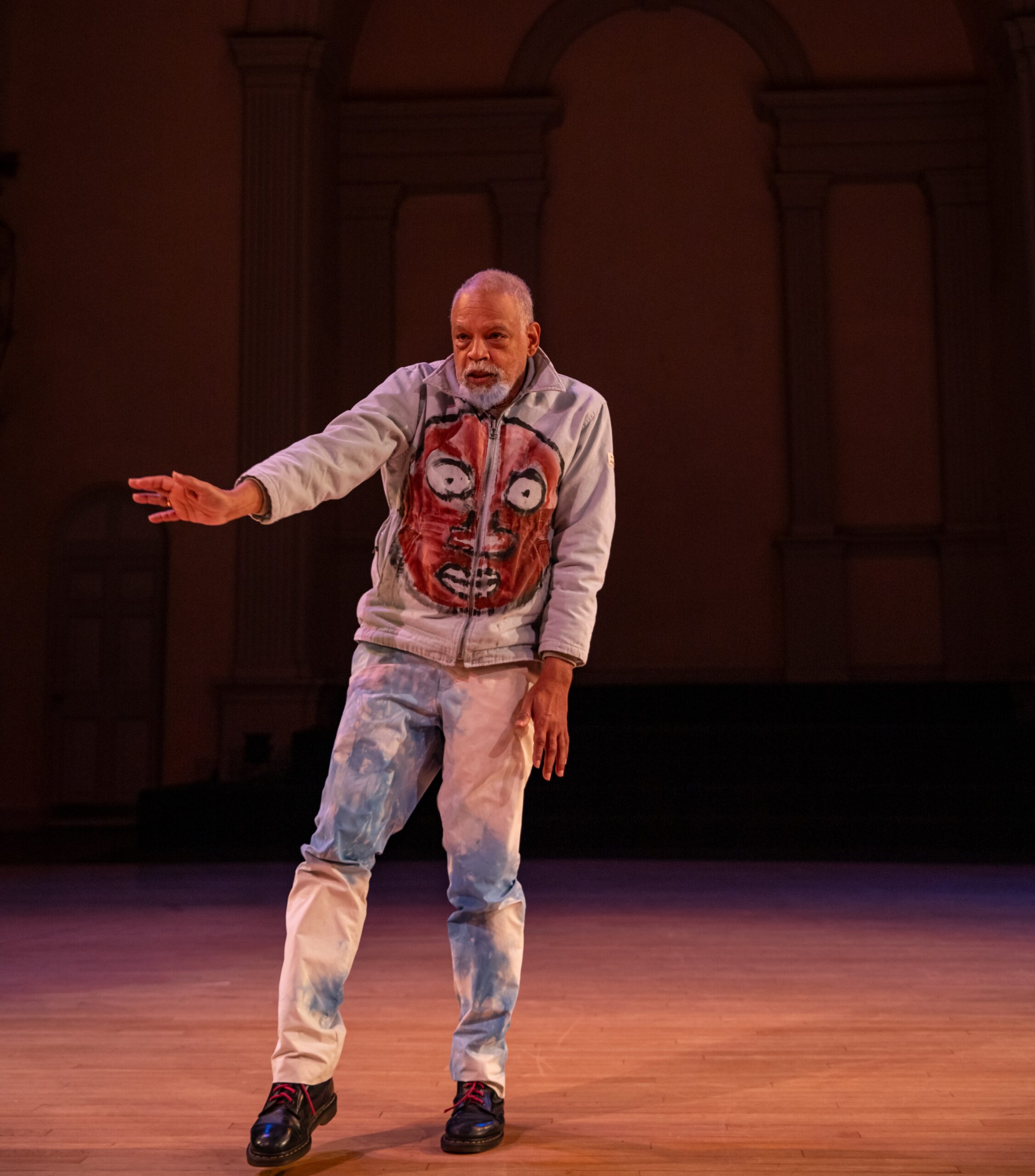

The performance’s musicality is introduced and underscored by composer-musician Andrew Clotworthy, playing keyboard and guitar throughout. Supporting the actors’ lines and actions, Clotworthy caught each cue, and also cued us, the viewers, into our expected emotional state. While I ordinarily complain about the overly-high volumes of theater music, here the sound was, if anything, too soft to achieve its full effect, even in the intimate space of the Louis Bluver Theatre at the Drake. The actors were generally strong, particularly (in the cast I saw), Dan Hodge (co-founding artistic director of PAC) as villain William Corder and Victoria Aaliyah Goins as heroine Maria Marten. They delivered each line with clear enunciation, appropriately exaggerated postures, and bold actions, keeping us well apprised of plot developments. A few well-known melodramatic protocols also encouraged our engagement with the form—frozen tableaux of dramatic movement, highlighting pivotal plot points; applause placards to insure that we knew how to respond; and direct address to the audience by various characters. We quickly caught on, hissing the bad guy and encouraging the fun when “village idiot” Tim Bobbin (played by Damon Bonetti, co-founding artistic director of PAC), bumbled through his antics. More such tableaux, placards, and actor-audience interactions could have been introduced.

What I missed most, though, was consistent attention to the rhythmicity of the movement and language, which—as described by viewers of these works back in the day—gave the “melo” to the drama. In Maria Marten, the musical flow, both from keyboard and actors, could have been pushed further so that the actors’ bodies sang the emotional arc of the story. This might have addressed another disappointment for me: I was simply unmoved by the plight of the heroine and her distraught family and friends. For me, the show was all fun, but in no way fearsome. Yet melodrama mattered to the viewers who filled those early theaters; they cared about those tormented characters scrambling through those cliff-hanging plots, and relished seeing their own scrapes, ploys and tragedies worked out to the satisfying end we all wish for—the bad guy “gets his” in the end, no matter who has suffered along the way.

The simple sets (by Brian McCann)—painted backdrops, a few items of furniture, and strategically chosen props (Michael Kortsarts)—worked well to create a sense of place and to forward the action. The characters, in period costumes (Bridget Brennan), spilled off the small stage and through the few available spaces in the house to carry the action closer to the spectators. I’m glad I got this taste of the theater of long ago; I’d love a heftier bite.

To join the conversation, follow thINKingDANCE and Theatre Philadelphia online and on social media to read, share, and comment.

Maria Marten, or, The Murder in the Red Barn, Philadelphia Artists’ Collective, Louis Bluver Theatre at the Drake, June 6-24.