I laughed at myself as I once again fell out of the turn. I was meant to be doing a series of what felt like impossible pirouettes, repeatedly rotating backward on my weaker leg, while my arms traced arcs in the air in front of me. It was November, and I was taking part in a repertory workshop with the Merce Cunningham Trust, jumping at the opportunity to momentarily embody the choreographer’s challenging and idiosyncratic movement language.

Now, sitting in the dark theater during a 3D screening of the film Cunningham, I smile as I hear Cunningham describe the creation of the piece Summerspace. He explains that the piece had become, seemingly unintentionally, full of tricky turns. The dancers had complained, repeatedly insisting they couldn’t turn, at least not like this. His response, a shrug in his voice, was that the only way to do it is to do it.

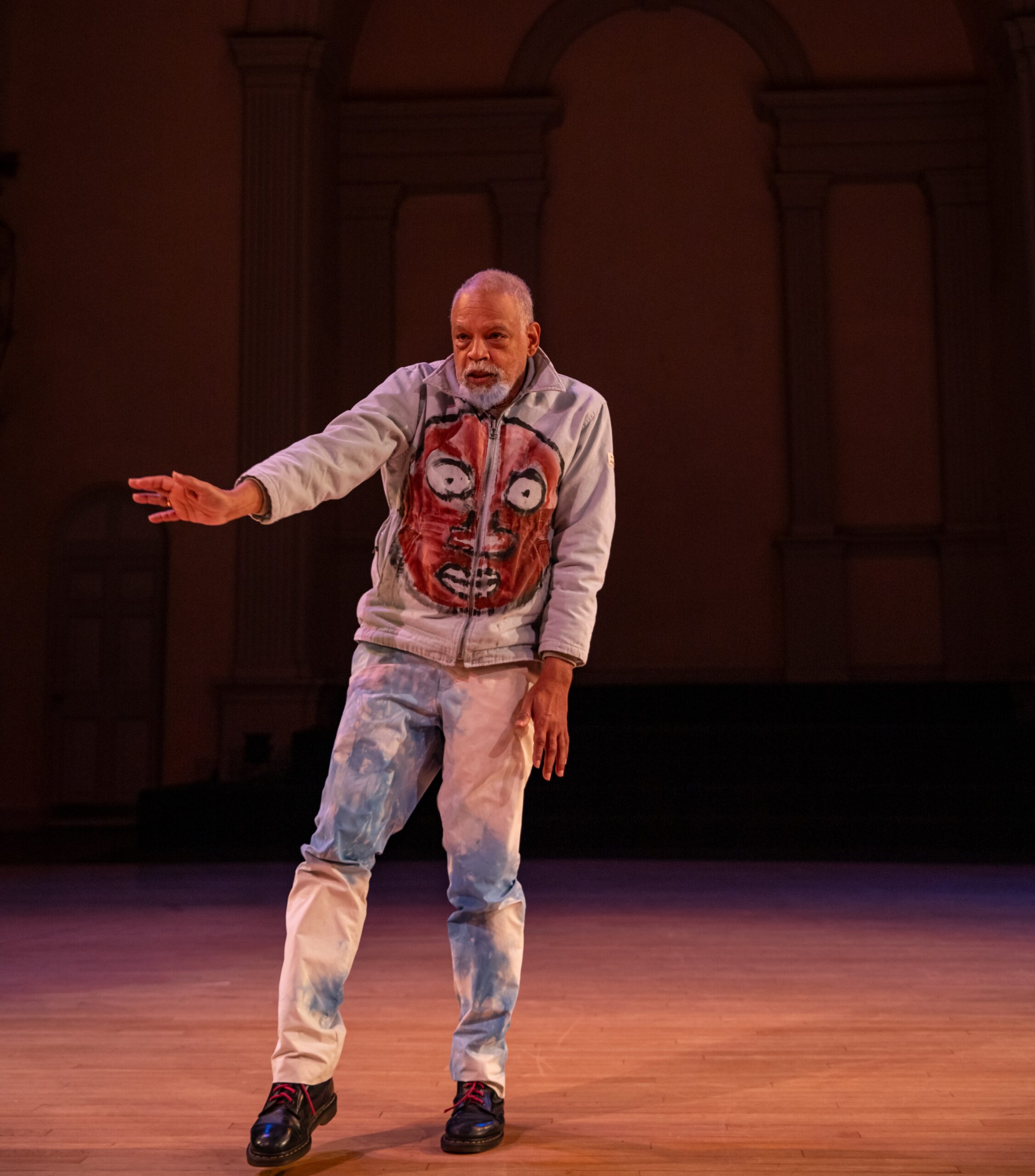

Somehow the dancers were able to take Cunningham’s advice to heart. Throughout Cunningham, in both archival footage and the restaging of older works performed for the film, dancers take on technically dense material with perhaps misleading ease. In one of the contemporary restagings (performed by dancers who worked with Cunningham towards the end of his life) a man melts into a deep plié while repeatedly punching the air in front of him. Standing again, he lifts one leg high into the air while wiggling his ribs from side to side. Watching this sequence, enlarged on the theater’s screen, I appreciate just how complete a stillness the dancer can maintain in parts of his body even as he moves other limbs with abandon.

This detailed focus and crisp vision is, of course, a benefit of film. Yet there are times, particularly in the sequences filmed specifically for Cunningham, that the result is almost too slick. I am confused by scenes filmed in what appears to be an ornate ballroom or mansion—the setting is sumptuous, almost surreal, but … why the opulence? It may be an opportunity to revel in the depth provided by 3D technology, giving the cameras space to swirl dramatically, but at times these settings seem to nudge otherwise abstract works towards unnecessary narrative.

There can be humor, even awkwardness, in Cunningham’s work, but few moments in this film allow those qualities to come through. At one point, a dancer lurches around the stage with a many-armed green and white sweater obscuring his face. It is a somewhat absurd image, but the swelling violins undercut the levity of the scene.

Elsewhere, however, I understand why the film is presented in 3D. The performances of Summerspace and Rainforest, in particular, are mesmerizing. In Summerspace, dancers perform in unitards painted to match the dappled, pastel backdrop. For Cunningham, the backdrop is made to curve seamlessly onto the floor, the slight distortion of the camera making it appear that the dancers are suspended in a world of swirling dots. Rainforest, freed of the constraints of the stage, gains a sense of endless depth. Andy Warhol’s silver mylar balloons bump against the foreground and float into the distance—when I hear an original recording of Warhol marveling at the beauty of his creations, I can’t help but share his awe.

As was the case with Rainforest, archival material frames contemporary footage throughout the film. Rather than cling to documentary norms of an omniscient narrator and expert interview, Cunningham centers primary accounts of the events it describes. Cunningham’s close relationship with John Cage, for instance, is recounted via a scrapbooked layering of archival videos, text taken from letters the two exchanged, and recordings of Cage’s music. I particularly relish the opportunity to see videos of Cunningham himself performing, his limbs simultaneously heron-like and gawky, his movement full of fascinating blips and flourishes.

Cunningham does not present an exhaustive account of Cunningham’s life, background, or creative process. Rather, it creates a texturally rich environment in which viewers can dwell for an hour and a half. Whether deeply enmeshed in Cunningham’s legacy or approaching postmodern dance for the first time, viewers will find thoughtful reflection on artistic meaning, insight into the challenges and rewards of collaboration, and many, many turns.

Cunningham, Directed by Alla Kovgan, Film at Lincoln Center, Jan. 10-16.