Perhaps there is more to be said about the soul-sucking drudgery of the modern workplace. The accoutrements of the 9-5 world are not unfamiliar: the insistent buzz of a sea of computer monitors, the zombiefying fluorescent lights, the resolutely jammed copier, the question of who will make cupcakes for Paula’s birthday, the lottery pool with its incipient fantasies of escape, the mystery of the yogurt that went missing in the break room fridge (even though it was clearly labeled!), the certainty that tomorrow will be much the same. None of this is new. And yet…

In a trio of short plays set to music, playwright and director Toshiki Okada has created a marvelously original vision of the life and death of the office drone. With this highly stylized, precisely choreographed production, Okada paints of a picture of cubicle life as a near-death experience. The triptych, entitled Hot Pepper, Air Conditioner and The Farewell Speech, is one of the most terrifying plays in this year’s Live Arts Festival, and possibly the most uplifting.

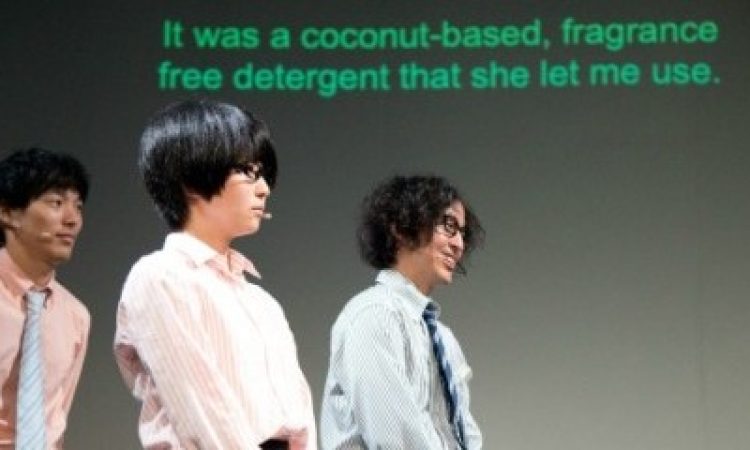

The premise is deceptively simple: in an anonymous break room in an anonymous office—simply realized by Ayumu Okubo and lit by Tomomi Ohira—three temps discuss from what restaurant to order food for the goodbye party of a co-worker who has been let go. The two women and one man take turns delivering rambling, repetitive statements—there is no dialogue; they barely register each other’s presence. As each stands to speak, however, they perform a unique series of movements based on commonplace gestures. The man speaks first, suggesting that they consult the popular magazine Hot Pepper for a recommendation. As his dialogue appears on the blank wall of the room in supertitles (the actors all speak in Japanese; the supertitles are in English), he enacts a sort of Franken-ballet. He stretches his arms out in front of him, collapses, shuffles, hops limply, and repeats. Meanwhile, he reiterates his point, revisiting the same sentences over and over again. The scenario is immediately familiar to anyone who has gone through the same motions every weekday and carried on the same conversations about the same subjects (“Sure is hot out today. Any plans for the weekend?”). In Hot Pepper, Okada dives deep into that monotony, never freeing any of the temps to break out into a less generic dance, nor allowing them to ever decide on a restaurant. His interest is in the repetition.

The music, also by Okubo, reinforces this interest. Spare chords struck on a synthesizer underscore the anxious refrain of each character’s speech. As the scene continues—for probably 30 minutes or so—the subjects of each speech begin to seem like obsessions. The conversation, such as it is, grows maddening. And yet, little deviations break through the simple choreography. The man begins to reach up, rather than out. When a shaft of blue light appears on the wall, one of the women appears to climb it with her hands. It’s all for naught, however. The scene ends as irresolutely as it began.

The second play, Air Conditioner, is more charged, but equally stultifying. A woman complains about how cold the office is—23 degrees Celsius, she asserts at least 20 times—while a wild-haired man rants about a political program he saw on television. The relationship between these two figures is murky, but still more pronounced than the first trio. There are moments where they actually seem to be talking to each other. And, underscored by an improvisational jazz score that builds from a drum solo and ends with a shrieking saxophone, there is a frenetic air of sexual tension and physical danger at play. The man makes muted phallic gestures with his tie, stoops to crotch level repeatedly and at one point openly thrusts. The woman is more jittery, brushing at her arms and legs, raising and lowering her skirt. It’s as hypnotic as Hot Pepper, and disarming, too, as the first play coasted on a complete absence of emotional narrative and Air Conditioner seems barely able to keep its under wraps.

Ultimately, however, there is no consummation. The play ends as it began, with the same phrases—physical and oral—repeated, this time louder and in unison. “I’m not kidding,” the woman says more than once. “I’m so cold and miserable.” The man responds “Hai (yeah)”, with the manic consistency of a nervous tic.

Surprisingly, my mind didn’t wander much during the first two plays. To the contrary, I found myself shifting my attention back and forth from the supertitles to the repetitive, rhythmic motion, almost panicked that I’d miss something even though I knew that it was all the same. The pieces mesmerized me, commanded attention, in a way that was confusing until the final section, The Farewell Speech.

Erika (Ikumi Aoyagi), the worker for whom the three temps are planning a lunch in the first play, is invited to give the eponymous speech. She begins in stillness, expressing a surprising gratitude. She moves stiff hands together and apart, then arms, then a small step side to side. “I may never be this happy again,” she says referencing her time at the office. As Erika begins a deliberate, slow motion version of the Charleston, she launches into a stunning soliloquy detailing her preparations for coming into the office that morning. She does not repeat phrases and unlike the other performers, her face is not a blank mask. She smiles throughout, even as her story darkens. It’s absurd and fatalistic and masterful. Okada allows the burbling cauldron of monotonous gestures and repeated words to boil over in The Farewell Speech, letting lose the pent up anxiety of the displaced worker and those who know they will be next. And he does so without abandoning the framework he set up using simple sets of repeated movements to telegraph a deep, existential foreboding.

As Erika finishes her strange, tragic speech, the other workers applaud and one remarks, “Soon we will follow you.” Naturally, this indicates that more jobs will be lost, but one wonders whether it also holds a promise of freedom, a physical and emotional escape. The play ends with the lingering possibility. Tomorrow will be much the same. Or will it?

Hot Pepper, Air Conditioner and The Farewell Speech, written and directed by Toshiki Okada, September 19-22, 7 p.m., Christ Church Neighborhood House.