Last spring, a photo of Steve Paxton appeared on the announcement of a gala invitation. In it, he is balanced upside down, standing on his head but without the support of his arms, which are glued to his sides. Seeing it, you imagine how in the moment after the shutter clicked, he toppled onto the grass.

I’d guess the era in which the photo was taken, with Paxton sporting a beard and long hair, would be early 70s, just as contact improvisation was taking root. Or maybe a tad before contact, when Paxton began discovering, with members of The Grand Union, that touch and mass combined provide ample grounds for physical experimentation.

Paxton-as-physical-researcher has taken many twists and turns. That phrase—twists and turns—signifies the meandering path of artistic inquiry. But it’s apt, literally describing a significant slice of what we could see in Paxton’s own dancing at Dia: the continuous research into the potentials of the spine—how it moves in relation to the pelvis and against it. Material for the Spine, which has been Paxton’s largest contribution to dance pedagogy following the advent of contact (whose repercussions on dance-making and dance practice are impossible to quantify, so influential has it been), took on the twists and turns with a searing microscopic level of examination.

What happens when the arm leads a spiraling roll and the legs trail behind? What happens when a c-curve remains constant in a roll so that hands and feet lead the body in a gradual progression along the floor, pelvis trailing? What happens when the initiator is the pelvis instead? And then, executed standing, what happens when these explorations are translated into a different relationship to gravity?

Methodical, curious trials working with such questions formed the heart of Material for the Spine. The cultivation of that level of awareness—beyond any particular form—is arguably Paxton’s greatest contribution to dance artistry. Whole generations of dancers, as a result of engaging with the practices he has developed, have been made sensitive, curious and respectful of the body’s sensations and delicate instinctual dances of balance which most often go unnoticed. Paxton was all about somatics before anyone ever used that word.

The Open Hand

One crucial lesson that Paxton taught was that each person is ultimately responsible for his/her own weight. So if you dance with a partner and feel them falling, the safest pathway, rather than attempting to clutch them, is to open the hands. To allow them to slide, or spiral, finding their own way floor-ward. Offering surfaces by sliding out a leg, or changing the angle of a back, is different than clasping with the hands. In the former case, each dancer has agency and choice. In the latter, not.

With a different kind of open hand, that is, not holding tight to contact improv practice as anyone’s trademarked personal possession, the growth of contact itself became mushroom-like, unpredictable and widespread. Like spores traveling on the wind, single practitioners could spawn whole new communities. Now worldwide there are many for whom this is their sole dance practice. It is a culture, a social gathering place, an ethos and a model for societal interaction.

Corporeal/Conceptual

Although history books include notable Paxton works like Intravenous Lecture (1970, which was a unique approach to making a political point and which Stephen Petronio recently revisited), or his parade of 40 walking folks in their ordinary clothes (Satisfyin’ Lover from 1967, recently restaged at MoMA), his formal dance-making that engages narrative elements, props and conceptual scenarios is likely less familiar to audiences. Later phases of his work—improvisations with percussionist David Moss, Goldberg Variations, PART to music by Robert Ashley in collaboration with the terrifically expressive Lisa Nelson—are, to me, less conceptual and less complicated to read, centering on Paxton’s own body and its potentials. In the early performances of contact, his focus narrowed deliberately to the physical—on animal-to-animal relationships to others minus psychological sidetracks. You could follow the mind of the body rather than puzzling out more complex implied meanings.

The suite of dances featured in the Steve Paxton: Selected Works program, in contrast, emphasized works with more complex interactions of elements. One—The Beast—showcased Paxton alone, dancing. The three other works in the show, Flat, Bound and Smiling, performed over two sold-out weekends, were rich with what could readily be seen as cues for meaning, although interpretations remained always in the eyes of the beholder rather than ever being spelled out in a literal way.

Flat (1964) is a sort of businessman’s striptease that reverses itself when all the clothing that has been removed and placed on hooks taped to the dancer’s body is once again, piece by piece, put back on. There are actions of circular walking, sitting, walking in a straight line. There are individual gestures by turn quotidian or heroic. The score offers leeway to the dancer in terms of duration and action, with specific limitations (a particular pose may only take place once, etc.). In this case, what was originally enacted by one performer is danced by two women and one man in the vast depth of a gallery of crushed metal sculptures by John Chamberlain; what was a solo becomes a suite of resonances.

Pictured L to R: K.J. Holmes, Jurij Konyar, Polly Motley

Maybe the way we are nudged into watching this slow-to-evolve work, with curiosity, is a direct counterpart to the deepening into awareness of sensation that Paxton cultivated in himself and others. How does her arcing path interact with his? What is happening that I can’t see behind that sculpture? How does this fugue of a trio continue to play out musically? We could thank Merce Cunningham for requiring audiences to be active watchers, co-creators, and for Paxton, who danced with Cunningham, the audience’s involvement would be a given. Also as with Cunningham, certain kinds of outcomes were not controlled, so he expressed pleased surprise later at the beauty of particular serendipities.

Paxton commented after the performance in the gallery talk, that writing about his work from the point of view that it is “about” something misses the point. (A fresh New York Times review by Brian Seibert had made several such assertions.) I am reminded again of Cunningham, in particular his comparison of experiencing his work to looking out a window and seeing birds fly (you notice pathways, speed, their actions) while hearing the sound of a fire truck’s siren. There isn’t a meaning to it, the two don’t have a particular correspondence and while actions are unfolding simultaneously, they don’t need to cohere.

So, from that point of view, when it came to Bound (1982), the longest and most complex piece on the program, I was particularly challenged to reconcile how the elements in it hung together, in part because its cues for meaning–a sound-score that includes what seem to be shots and sirens, a cradle and a rocking chair onstage as the piece progresses, with the performer sitting between the two, an upstage flat and a costume of camouflage fabric—all point to specific meanings: wartime, strife, life arcs.

Jurij Konyar, who performs Bound, has become an uncanny interpreter of Paxton’s improvisational scores, finding nearly identical physical pathways to many that the younger, springier and stronger Paxton found. His action alternates between the stagehand-like pedestrian—carry this, move that—and dancing. He is “neutral” in his delivery though. So it’s elements like the layering of the plaintive singing (so familiar from the late 70s) of the Bulgarian women’s choir that paint a wash of broken-heartedness over the whole.

Maybe I have misunderstood how Paxton has opted to use “signifiers” as free-floating objects, and for us to place them in our own mental collage, just as Cunningham thinks of birds and fire trucks. Yes, they are recognizable things that create a particular environment, just as birds and fire trucks are about 1960s New York street life. But beyond that we are on our own.This is not millennial dramaturgy with its emphasis on shaping how the viewer “makes meaning.”

In the Q&A following the performance, Paxton explained that he was indeed thinking about war and soldiers returning from it. This leads me to question how the Judson ethos in this work—that any materials might be used in any way at all—reads today. If material is as charged and topical as in Bound with its anti-war implications, is there any duty at all to create a comprehensible whole? Are we as open now to any material at all being used in any way at all? And how does that square with Paxton’s stating that reading the work as being “about something” misses the point?

A Solo to Measure Time

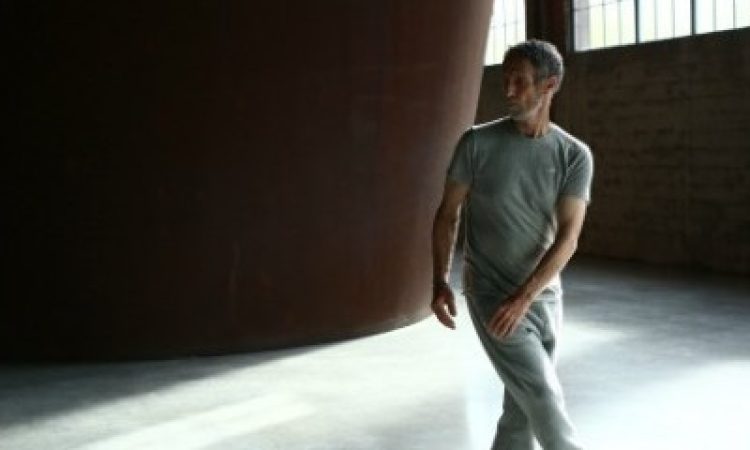

I wrote about The Beast earlier (here) so was intrigued to see it four years later. In gray sweats, in an industrial gray and brick space, against the monumental curving surfaces of Richard Serra sculptures, Paxton seems more circumscribed in his range of motion. He invites us to witness him in conversation with the dictates of his spine, his balance, his instinctual gesture-making. He is as much an observer as we are; not that he is without control, but that he is listening to instructions from within.

He plays, he recalibrates, he hovers with a physical thought. It seems to complete itself and he walks along an arc to a new spot. This happens three times. Then he leaves, having shown us a digest of the possible.

What creates the “authority” that Paxton has? The Beast is quite stripped down, functioning on a near-micro level. Watchers are completely magnetized. The other selected works are in some ways playful or absurd, yet the audience appears compelled to take them completely seriously. Is this the result of an august history? Or is there something in Paxton and his performers’ own straightforward conviction that gives depth and credibility to everything they do?

Perhaps with such a figure it’s possible to err on the side of taking him/her too seriously. When I left the Trisha Brown Dance Company Paxton said to me, “now you can get her out of your body.” I wrestled a long time with what seemed to me the utter impossibility of this, because it was he who suggested it. But bringing the subject up 30-some years later in a conversation at Dia, I compared how integrated in my own physicality Trisha’s movement became with the way that Konyar is now “embodying” Steve himself. Paxton agreed that transitioning away from a mentor’s influence is perhaps different than he initially stated. He mused that getting a choreographer out of your body—undoing the imprint they have made on your own instinctual ways of moving—might be more (and I paraphrase) about not being bereft when you are no longer doing that work. That makes sense to me.

I am very pleased that for the showing I attended, Smiling (1967), performed by a rotating cast, featured Paxton and Lisa Nelson, his longtime artistic partner. She has always been an utterly magnetic stage presence for me, not unlike Fellini’s wife, the actress Giulietta Masina, who, with her diminutive delicacy and extraordinarily communicative face, evokes both tenderness and ebullient play. Several duets for the two of them have been performed many times over the decades. This score, which essentially asks the two performers to smile, but in a forced, uncomfortable way—fake smiling—is rich with awkward fun.

Paxton commented later that when he looks out during this piece the audience always seems to be smiling, despite the discomfort implied by it. We recognize how strange it is, how silly. And the two of them enact it with sly wit, a perfect end to an afternoon in sun-drenched galleries watching timeless historical works.

A long life in dance has up and downsides. The body becomes less able in a variety of ways but more eloquent in others. The accumulated range of work can be fanned out and understood developmentally, as in the retrospectives recently staged for Paxton’s contemporaries like Brown. The fact that his work is now being showcased at venues like Dia (and, as this is being published, at the Walker Art Center) is of great value to younger artists, to audiences in general and to longstanding admirers, like me.

Steve Paxton: Selected Works, Dia:Beacon, October 17-19 and 24-26. Performed by K.J. Holmes, Jurij Konjar, Polly Motley, Lisa Nelson and Steve Paxton. http://diaart.org/programs/page/84/2216

Material for the Spine: A Movement Study (DVD-rom). Steve Paxton. 2008. Contredanse. Brussels

All photos by Paula Court, used courtesy of Dia Foundation

Steve Paxton’s response to this article is here.