All photos by Mark Garvin.

If you’re at a theater event that lasts all night, your expectations about being entertained change. You don’t imagine that either story line or action will move along quickly. A different kind of watching happens. Settled. Appreciative of minute shifts. People come and go, get food, drift off in reverie. And the set-up is probably intimate, with people sitting close enough to see the sideways shifting of eyes and tiny flicks of fingers that make Kathakali, one of those theatrical forms traditionally performed in long durations, rich in what a friend termed “tiny virtuosity.”

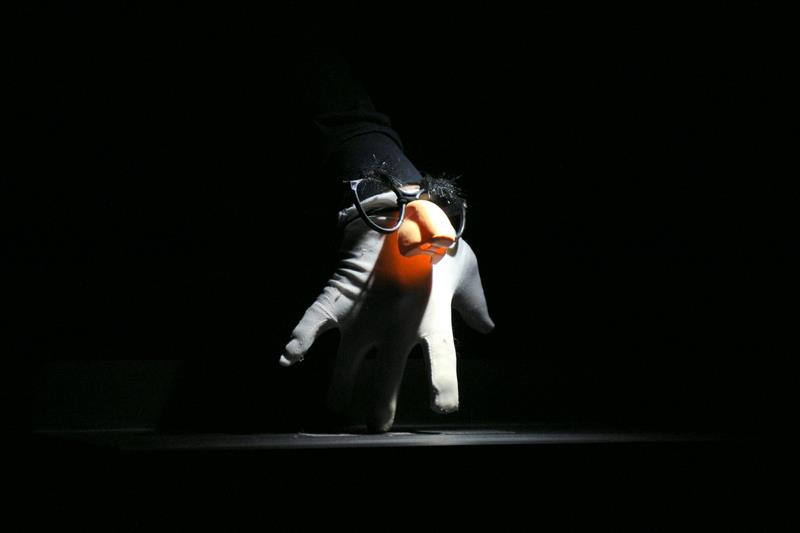

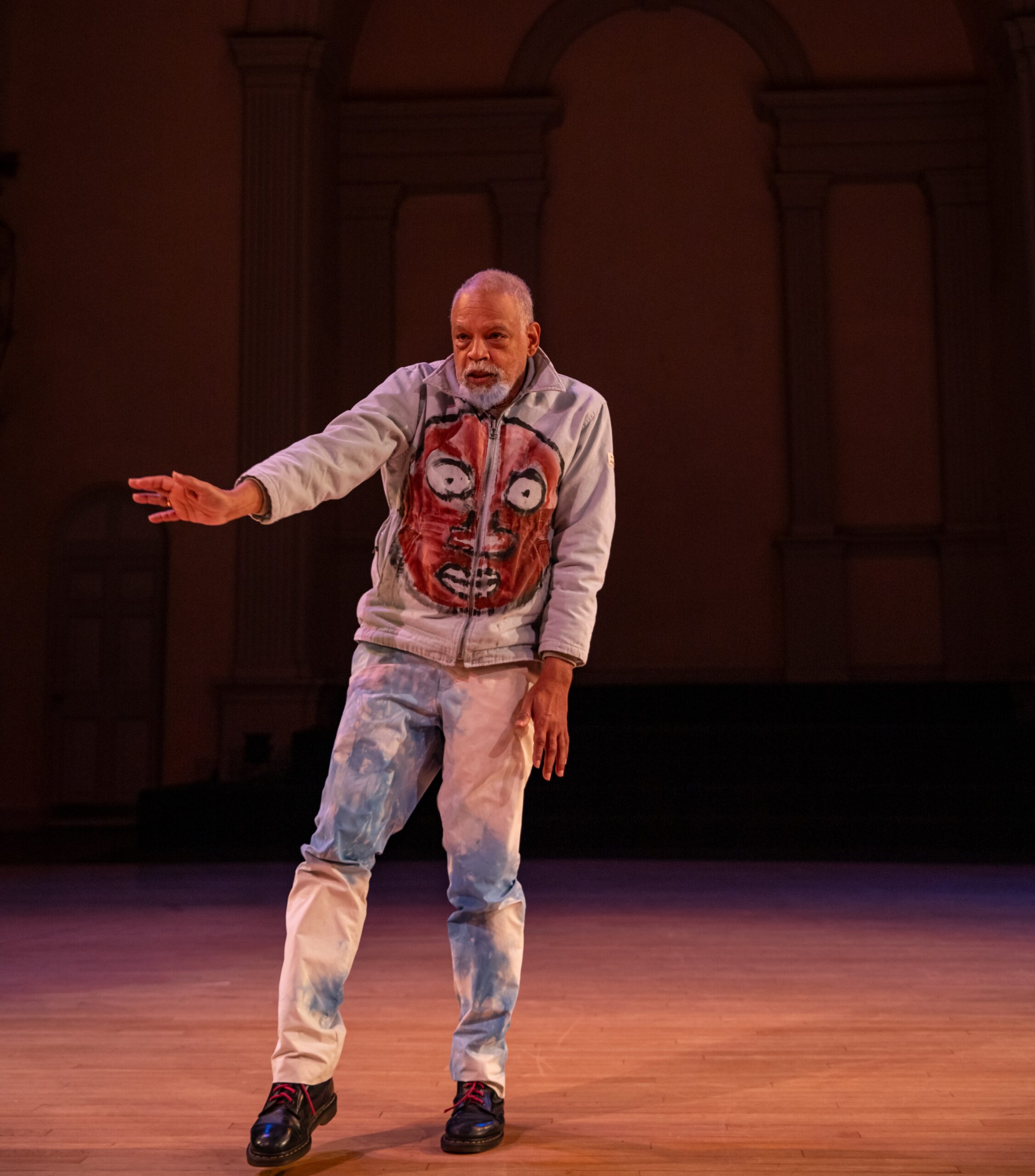

Until attending this performance, given as a two-hour presentation on the Annenberg Center’s proscenium stage, I’d seen only photographs of Kathakali—its dancers in ornate costuming and highly stylized make-up. Through poufy skirting and layered jewels and jackets, they seemed to be intentionally made to look heavy (with weight as a sign of power and wealth). Yes, that was the look here in the three sections of what was originally a much longer Kathakali spectacle, Nalacharitam, given by the troupe of Sadanam Balakrishnan and presented by Sruti, the Philadelphia-area organization dedicated to presenting the music and dance of India. The players’ faces were colored in bright green and red (for the king), pale skin tones and rouge (for maidens) and oranges for the golden swan (skillfully convincing with a moving beak!). Apparently donning the make-up alone takes nearly the full day.

Kathakali historically began, like opera, with the main performers both singing and moving. Later those roles were separated, the sound of the voice and the gestures accompanying it no longer coming through one person. Here, the vocalists were two men accompanied by percussion. They continually spelled one another, each voice lapping over the other like waves, and sometimes sang in unison, with the sound flowing on nearly nonstop for two hours. The costumed performers represented the characters, in most cases acting out, with hand gestures, each sung phrase.

What gestures! An elegant sign language of mudras, traced like flutterings of rare birds. A conductor’s hands deliver all manner of nuance: these actors’ hands are equally eloquent. Their bodies too were subtle, projecting power or diminutiveness through stance, making the slightest weight shifts compelling.

As a nod to those who may not read or retain program notes, each section of the performance (as with bharatanatyam performances recently presented by Sruti) was preceded by a verbal account of the plot points to be represented. But for me, unfamiliar with the traditional story, the moment by moment experience was like watching people in conversation when you don’t really know what they are talking about. Slightly befuddling. But I was magnetized.

The plot of this drama:

Part 1 – King is enamored of young maiden. (Alone he thinks about this.)

Part 2 – Swan comes to king and they talk it over.

Part 3 – Young maiden with her maid is visited by swan who intercedes for the king, bringing together the pair of lovers.

The drama unfolds with hardly any of the big traveling-through-space moves that Westerners are accustomed to. Here, only the swan flying on and offstage, arms lightly flapping and turning in circles, travels in that familiar way. Otherwise, this extremely refined dance is largely spatially static.

I was sitting relatively close up, although far on one side. This helped in picking up detail, although I knew there was a great deal I was missing. I wondered at the experience of those toward the back of the nearly 1000-seat hall.

When I went to Bali, thirty years ago now, the dance-watching experience stunned me with how sharply it contrasted to the downtown New York scene I was familiar with. People knew all the (mostly Ramayana-based) stories enacted, they were relaxed in the audience, chatting, going off to eat something, or perhaps sleeping a little. The Western convention of silent attention was absent. There was more ownership on the part of the audience, more sense of the ongoing interweaving of performance with their daily lives. After all, performances took place nearly every night, crucial parts of village rites in which all partook.

But reflecting on this now, as a result of encountering Kathakali for the first time, I experience an edge of unrealistic nostalgia. I seem to be more attached to the traditional forms of cultures not my own than to traditional forms of Western dance. Change is inevitable everywhere. Adapting long-durational forms to contemporary audience expectations is part of the vital evolution of dances. How can they live today?

In light of all this, what of my first experience with Kathakali? I am glad to have seen it. Glad to know the extreme expressiveness possible with actions primarily of arms, hands, and facial features. Glad to hear the lovely tag-team singers whose voices ascended and fell in complex showers of sound. And glad that this tradition, one of the world’s oldest forms of theater, continues to live on the contemporary stage.

Sadanam Balakrishnan and Troupe in Nalacharitam, presented by Sruti, Annenberg Center, May 2. http://sruti.org/concerts/2015/Nalacharitram/Nalacharitram.asp