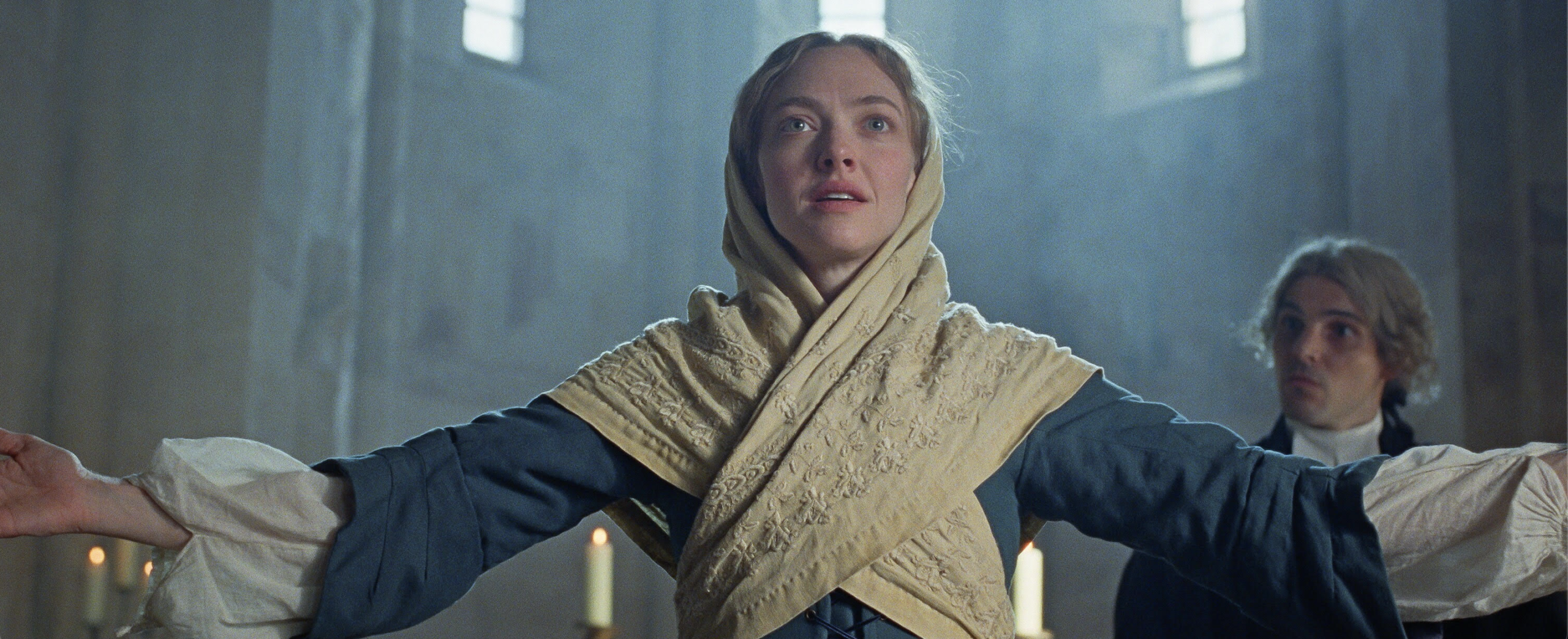

With the opening of Sophocles’ Antigone at the Wilma Theater, previously reviewed by tD’s Julius Ferraro here, thINKingDANCE presents an interview by Jay Oatis with its director and designer, Theodoros Terzopoulos, the long-standing artistic director of the Attis Theater in Delphi.

Jay Oatis: How does your creative process begin?

Theodoros Terzopoulos: The first time we came here was in 2013 as part of the Fringe Festival for a production of AJAX. This past year, Blanka Zizka [the Wilma’s artistic director] organized a workshop, inviting different actors. Four of the actors who participated in this workshop are in this production of Antigone. They participated in my international workshop in Athens that I manage every year in July. After I came here in January 2015 to lead the workshop to make the final casting, I brought three actors from my Attis Theater company. It was very, very important that most of the actors in Antigone came to Greece to be trained and prepared. It’s very hard work for the body and the voice, mostly for the diaphragm—concentration, energy, discipline, I need all of this for a tragedy because tragedy is a different kind of theater. It’s not drama. No chairs, no tables, no smoking—nothing. You’re naked on the stage, like dance.

J: What did you work on with them during the rehearsal process?

T: I started immediately with the text. You usually have to create a performance in four weeks. Luckily, we had six weeks. I started immediately because I came here with a concept already prepared—the structure of the performance, the adaptation of the text, everything. I worked on the concept a year ago: no improvisation, trying to find ideas—small ideas—during rehearsals. During rehearsals I found different access points for Antigone when working with Jennifer Kidwell. I tried to understand American history better. For example, I’ve loved the song Summertime [from Porgy and Bess] since my childhood; I know the historical, sociopolitical origin of this song. I used another song in Greek that the chorus sings, When can I, where can I find my soul? These songs tell similar stories on a historical, sociopolitical and existential level, too. I tried to create a bridge between the two cultures. I didn’t say to the actors, “Please memorize the text immediately and we’ll start with that.” I focused on the inhalation, the exhalation, the body; a few words, a few phrases, not the whole text—focusing on key phrases. After that they continued to memorize the text and we made sure they could memorize it well. We had enough time—we were ready in three weeks.

J: What inspires your design process? Where do you start?

T: I went with the archetypical schema that is the circle. I wanted the design to reflect the story. There’s a crazy person at the back of the stage who is speaking throughout the production. Tragedy is madness. It’s not theater with logic, theater that’s dialectic. You see Creon and Antigone in conflict—there’s no communication. Creon says, “This is my position.” Antigone says, “This is my position.” But they never create a bridge. Like today, there are no bridges between the people and those in power.

Anarchy, Rebellion, the Boston Marathon Bombings

J: Anarchy and rebellion are two major themes in this work. The press release mentioned you were inspired by an essay about the Boston Marathon bombings. Polyneices and Eteocles can be compared to the two brothers who organized these bombings. There’s also mention in the production of Eric Garner, Michael Brown, Sandra Bland, and Trayvon Martin. Do you think that people will do anything to defend their assumed rights, even if it might hurt others?

T: Sure, I was inspired by this event in Boston. In tragedies there’s a deep, problematic event—like a civil war or conflict. Thirty years ago I created an international symposium in Delphi on this topic, based on Antigone and Eurypides. I was also inspired by neo-racism and neo-fascism. In this production they march forward with a board with pictures, of victims of past civil wars—some from Iraq, some from Afghanistan, and two people from Ferguson. The second time they march, they mix the names of Greek victims (from the original) with the names of these more recent victims—Milanipos, Rebecca, Eteocles, Sandra—to make the tragedy more present. A tragedy must say something about our lives now. It’s very important that it speaks to us. I created this channel to stay close to the people, not to stay only in the story. In ancient Greek language the story itself is fantastic, because of the musicality of the language. In modern Greek or English, we lose maybe 70% —we hear only the story, not really the colors, the rhythm, the voice, the measure.

J: I’m fascinated by the idea that the classics still hold strong. Like Shakespeare, Sophocles left a legacy of work that can still be staged today. Are there any contemporary playwrights who you feel are similar? Who is writing the next Greek tragedy?

T: I don’t think there are similar playwrights. We can see this dimension in Shakespeare’s plays. They have the same big dimension as Greek tragedies. There’s this conflict between human beings and the gods. It makes the tragedy much bigger. You have to create big ideas. It means you need big bodies, big energy, big structure. There’s always a relationship with the gods.

Tragedy and Pop Art Theater

J: I saw Angels in America here at the Wilma Theater a couple of years ago and that play had a lot of weight. I feel like I’ve seen productions that lean too much on humor or typical dialogue, typical conflict. Angels in America deals with very heavy subject matter, and does so in a way that’s very “big.” Do you think that’s still considered drama?

T: The idea in the U.S. is to make pop art, to sell out the box office, whether it’s a tragedy or Shakespeare or Heiner Müller. They often choose crowd pleasers to fill a theater—it’s the commercial way. This is pop art. But it’s impossible to make a performance of a tragedy in a pop art way. It’s ridiculous. It’s impossible.

J: I was in the Wilma lobby before the show and my friend and I were probably some of the youngest people there. I thought, “Ok, this audience knows Sophocles, they know the general story. But I know they’re going to see something very different.” You’re taking a classic and remixing it.

T: The concept is a post-war story. After a civil war, after the atom bomb, you see the people. They are poor people. They are victims. They are not winners. You see the story not from the winners but from the opposite side.

Post-Modernism vs. Classical Modernity

J: Your work is deeply connected to live performance. There’s a trend toward more interdisciplinary collaboration in much live performance right now. In what direction do you see theater going?

T: You’ve seen that I don’t use video. Everything is very simple—filling the performance space with energy, and not many entrances or exits. I’m not a post-modernist; I create classical modernity. The structure is archetypal but the form is modern. It’s not old, conventional theater…. The wave of post-modernism in Europe is finished. I was using dance to make the body theater forty years ago, and I was one of the first.

J: An audience member can go see an opera in a movie theater. What do you think about how theater is being presented now, the influence of technology on the audience experience?

T: This is something we were talking about thirty, forty years ago because the theater is always in crisis. [Terzopoulos points to this writer’s iPad.] You can watch theater, dance, everything on here. But the people need the energy of the theater. Theater is like an erotic act, with its exchange of energies. The theater has religious origins. The audience is more attentive. When I watch people watching our production, they don’t move. They are very concentrated. To see, to understand—it’s not just the story, there are other layers under the story. Tragedies pose questions. It’s not a light play, where the themes are superficial, and you go to the theater to forget everything. Tragedy is different. You have to create memory with a tragedy. We go to theater because we want to forget everything, but with tragedy it’s the opposite. The material draws out deep memories. It’s like a trip.

J: Do you have plans to have your company continue after you retire?

T: If I retire? I’ll try not to retire. Sure, there are people who will continue my work. There are books on my methodology—one is to be published by Routledge in about a year. There’s my assistant director [Savvas Stroumpos]… two or three people. They don’t imitate me. They’re very good directors. They took the principles but they create their own language.

J: How has the economy in Greece affected arts funding?

T: I have a private theater. There’s no support from the government. We work very hard—I direct shows throughout each year. We have a large audience and we’re always sold out.

J: This Antigone was very physically demanding. In terms of care for the actors, what advice have you been giving them? How do they work through this run?

T: That’s part of the reason I’m here—to speak with them, to rehearse and rework scenes. Give them advice. It’s cleaner, more concrete. The acting is better. I’m staying through the rest of the run.

Antigone by Sophocles, directed by Theodoros Terzopoulos, Wilma Theater, October 7–November 8, www.wilmatheater.org