Greed (and its attendant shortcuts), accidents, and natural disasters continue to inflict trauma on survivors in their wake. Loss of dignity, of self, of family, of home also result from entire communities being ravaged by systemic violence and disenfranchisement: psychological and physical abuse that goes unchecked behind closed doors, kidnapping and rape employed as instruments of war, and so on. The scars engraved in people’s souls and bodies through trauma are deep and rugged.

A Korean man, Kwon Oh-hyun, 26 after the 2014 Sewol ferry disaster that took the life of his younger brother, Kwon Oh-cheon, lost more than fifty pounds in the half year following the sinking. He could hardly keep any food or drink down. A doctor encouraged him to seek counseling, but he refused. “The pain I feel over my brother’s death is my last connection to him,” Kwon said. “If I lose this anguish, I will have fully lost him.”[1]

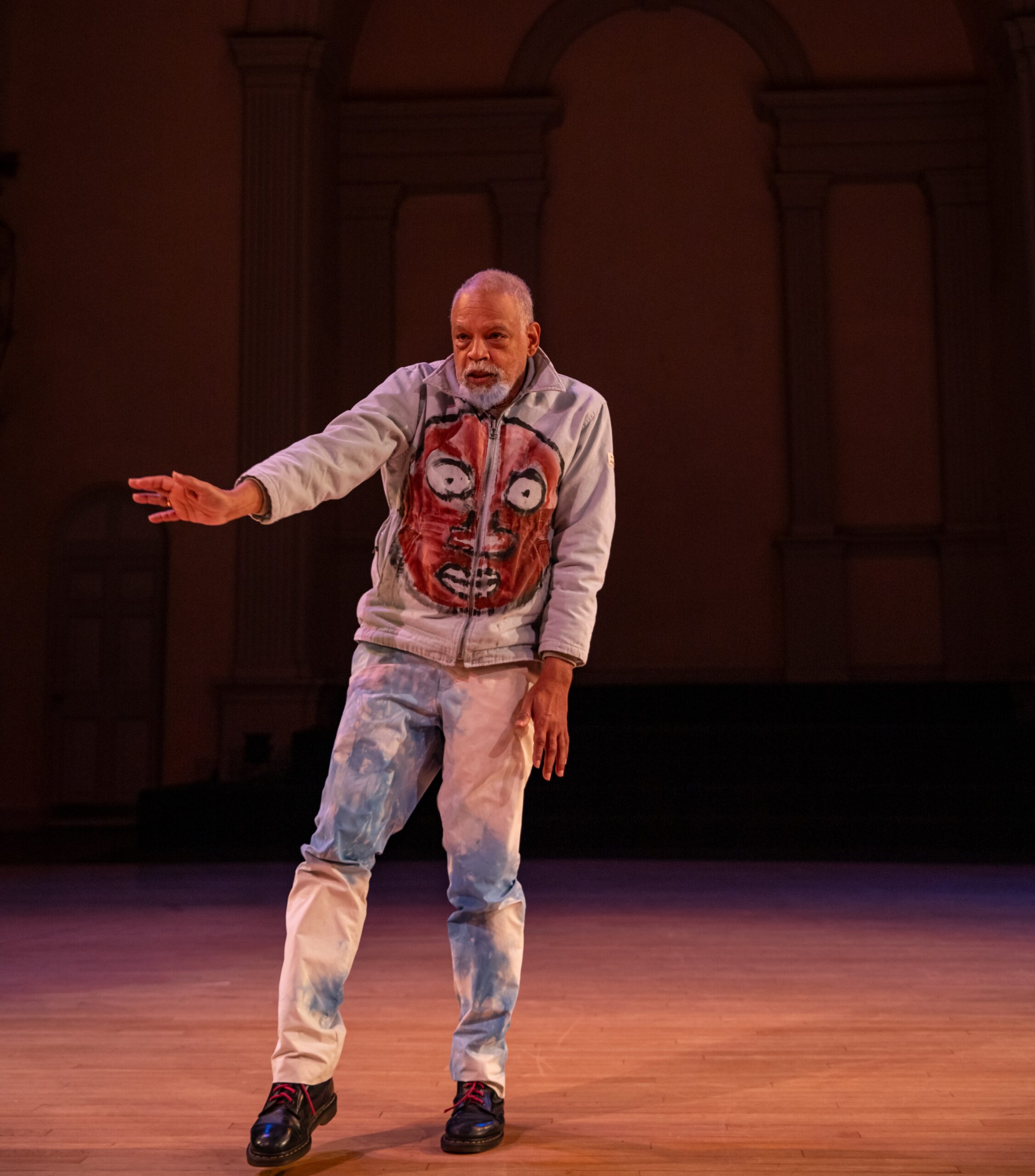

A recent volume on the healing of trauma declares that, “the body keeps the score.”[2] Our bodies hold our stories. Dancer-choreographer Jungwoong Kim’s pieces for SaltSoul harness the aesthetic, kinesthetic, and spiritual potency of embodied, auditory, and visual practice, exposing grief that registers in the sinews of our being and cultivating compassion.

July 10, 2016 pop-up performance: Dilworth Plaza/City Hall

Whereas the site of the Salvation Army building collapse at 22nd and Market Streets was, indeed, the site of Kim’s July 7 performance addressing that tragedy, Dilworth Plaza became the locus for a pop-up dance referencing the capsizing of a ferry on the other side of the world. Kim chose Dilworth Plaza because of the presence of water (in the form of a fountain in which dozens of sprays of water shoot upwards at various intervals) and people, especially children. Before the ferry sank off the coast of Korea, the 325 children aboard had been laughing, playing, talking, texting, and singing.

In anticipation of the July 10 event, Kim spent time at Dilworth Plaza. On any given day, a variety of individuals are present, paying attention to divergent elements of the space. As Kim played, moving in and out of the fountain, he remembered, “A bunch of different people looked at me in different ways. Children knew what was going on. Two kids copied what I did the whole time. I enjoyed that so much. And that’s why it was important that whoever was present on the day of the pop-up would be involved with that piece. We could create the score together.”

Indeed, Kim and his collaborators Germaine Ingram, Marion Ramírez, and Merián Soto, joined for this pop-up performance by members of the local Korean community Mel Lee and Jae Wook Shim, entered the fountain in their yellow shirts, engaging in play and exchange of movements with the children delighting in the water. Yellow ribbon had been used to symbolize the victims of the ferry disaster. By chance, the yellow was repeated in the umbrellas on the plaza. Kim described his ensemble of artists as a sponge—absorbing the place without formally announcing their arrival. “The kids, from the beginning to the end, were involved in the piece. They recognized that the yellow-shirted people were especially playful. Their open minds allowed us to explore together.”

Ingram also felt the resonance of the site with the ferry tragedy: “The water [in the fountain] rises in unexpected gushes and then subsides. That seeming randomness, from our perspective of moving within the water, made the space particularly significant. This unpredictability is embedded in the design of the fountain.”

Musician-composer GaMin Hyosun Kang (known professionally as gamin) played the piri, a cylindrical bamboo oboe whose sound can seem to mimic that of a youngster’s voice, on one side of the fountain. Children gathered round, mesmerized; some asked her about her instrument. Others just followed as she walked alongside the dancers.

The performers, at one point, walked forward through the fountain, and then backward. They rolled, slowly, through the water, finally joining in a sculptural representation of the ferry. Another member of the local Korean community, Jeongrye Son, an immigrant in her late eighties, appeared in traditional Korean dress (hanbok) from the far end of the fountain, traveling with measured steps on the winding path that cuts through the water streams as they shoot upwards, gracing the air with traditional Korean dance hand gestures, arms lifted to shoulder height. Every so often, she took gentle dips, bending her knees just slightly, as she made her way forward. Rainey’s plaintive saxophone was stunning in combination with Jeongrye Son’s poignant emergence. Some children rolled with the other dancers, evincing a sense of belonging to this community celebrating the youth who, too, once played without a worry in the world.

Ingram: “Towards the end of the event, when we were all creating that architecture, pushing against one another, one little kid about two or three years old was so invested in what we were doing. He came up on my right and I said to him, ‘Push,’ and he started to push on Marion’s leg. He was really going at it. He (in his diaper), and his brother who participated too, understood that they were part of this.”

Mel Lee, one non-dancer in the performance, had spent time over the past two years working with a Philadelphia Korean-American organization called SESAMO, an acronym for the Korean that translates as, “People in Solidarity with Families of the Sewol Ferry.” The group has been searching for the truth about the ferry sinking and subsequent rescue efforts, reacting to the obfuscation and lies by the Korean government and media, and led by their ache and compassion for the impacted families. Kim had attended some SESAMO gatherings, eventually suggesting that members join him in a dance, as, in part, a way of acknowledging and releasing some of their own sorrow. Lee agreed, unexpectedly finding “a sense of liberation and peace” through engagement with this tragic history through movement, while still holding within her the implications of “all this injustice and sadness.”

Jeongrye Son told me that she had asked to be part of this event, longing to do something public in response to her “heartbreak at the loss of all those young lives.” She added, in conversation with Mel Lee, “I can’t stop pounding my chest thinking of the bereaved families, because I know the grief. I know it because I, too, suddenly lost mine in an accident.… I’m turning ninety soon, and there’s not much I want in this world. But, should we not help the kids and their parents resolve their grief and resentment? Should we not do anything to stop this kind of tragedy from happening again? It is now not easy for me to move about, and I feel my memory is not as clear as before. Still, I am very thankful that there is something I can do, no matter how small.”

Ingram: “For me, the most important thing about both these pop-ups was the sense of collective trust that emerged within the ensemble. I think that was really important for us, and will be as we move forward. The pop-ups were originally going to be a marketing tool [promoting the October performances]. But much more important than that was how working on these pop-ups affected our sense of ourselves as a collective. I don’t think there’s been anything more important to building shared trust than doing those pop-ups. Because of our coming to consensus on a structure and executing that structure [at both sites], I think each audience absorbed some sense of our shared intention. If they paid attention at all, they saw that this group cared enough about something to create a structure and to invite people in that space to be part of it. It was enough for me that those two little boys at Dilworth Plaza felt they had a place in that structure. I hope that’s an experience that they will remember.”

Kim studied Korean traditional dance in his younger days in Korea. One of his teachers shared some of the movement aesthetics of Korean shamans with him as well. Kim incorporates aspects of those aesthetics in all pieces that make up the SaltSoul project. They inform his creative process that also includes the integration of music and experimental video with Western post-modern dance. The long cloth that was so central in the 22nd and Market Street performance, for example, harkens back to the extended sleeves that are common in many traditional Korean dance costumes. The dancer flicks her wrist or swishes her arm, sending the sleeves floating upwards, before falling back towards the ground.[3] Even improvisation within SaltSoul shares resonances with the improvisatory nature of shamanistic ritual. While the shaman is moved by the fluctuating energy of the deities, Kim has noted how he responds to the energy of the site.

Kim and gamin had together visited the mourning site of the ferry tragedy in Korea where photos of the hundreds of youth now hang. “It was heartbreaking,” recalled gamin. “I had cried just hearing the news, and then, once I was at the place, it just overwhelmed me. We met the parents. The feeling was heavy.” gamin approached development of the musical accompaniment to each of the pieces by both interpreting the dancers’ movements and creating music resonant with the sounds of accidents—leaning, tossing, creaking, crashing—evoking chaos and fear. “Those are the pictures in my head as I select an instrument and compose a section of the sound.”

Musician-composer Bhob Rainey noted that for those in this collaboration who might not have been directly impacted by any of the tragedies, the overall project makes apparent “what we all share—a sense of how quickly things can disappear and how we’re never prepared.” Rainey had collaborated with Kim and Ramírez once before, and “trusted them to be careful not to pander to tragedies.” With this expanded group, individuals are meeting and working with people they might have never even met otherwise, and those encounters influence the ultimate performance. He added, “At Dilworth Plaza, I didn’t know what to expect. That’s where I first met Jeongrye Son. And there was no question whatsoever of what I should do when I saw her move.… For artists engaged in this work, it’s imperative to find the space to allow the creativity that’s already there” to blossom.

Rainey also hinted that at the ultimate Asian Arts Initiative (AAI) performance of SaltSoul in October, audience members will observe a ritual-like performance that evokes a sense of presence in the space. Elements of each of the performance events (at 22nd and Market, Dilworth Plaza and AAI) will, Kim hopes, inspire heightened awareness of the world around us and of individual and community anguish, and a sense of responsibility to one another. The artists in this endeavor together fashion spaces in which all may mourn and pay respects, as they please.

Merián Soto described Jungwoong’s use of improvisation as “evoking alternative states of being, and generating a strong sense of connection” among the performers. Through their collaborative creative process and presentation, and their forethought (researching the events, speaking with those who’d lost love ones in these tragedies and with professionals dealing with trauma and sudden loss), they also model care for one another and the larger whole.

Other artists’ work, too, engages with sorrow, trauma, and bereavement. In September 2016, conceptual artist Taryn Simon directed a performance that included professional mourners along with sculpture and sound at New York’s Park Avenue Armory, exploring facets of grief. More than a decade ago, Susan Sontag wrote about the relationship between visual imagery (photography, painting), and suffering[4]. Considering mainly representations of the atrocities of war, she contemplates how those images “cannot be more than an invitation to pay attention, to reflect, to learn….” SaltSoul may hint at elements of a tragedy on a city street and one out at sea, but it never aims to re-create those calamities. Instead, it arouses empathy in the viewer for those who’ve experienced the overwhelming rupture of sudden, dramatic loss, and speaks evocatively, through live and recorded sound, gesture and movement, light and shadow, and experimental video, of those taken too soon.[5]

___________________

*This is the second part of Toni Shapiro-Phim’s reflection on the background and pop-up performances preceding SaltSoul. The first can be read here.

Toni Shapiro-Phim is a cultural anthropologist and dance ethnologist. She is Director of Programs at the Philadelphia Folklore Project, a local arts and social justice organization.

SaltSoul http://www.saltsouldance.com/home.php at the Asian Arts Initiative, 1219 Vine Street, October 6, 7, and 8 at 8:00 pm. http://saltsoul.brownpapertickets.com/ . Additional performance within art installation , habitus, by Ann Hamilton on Municipal Pier 9, 121 North Columbus Blvd., Oct. 9, 7 pm, free.

[1] http://www.latimes.com/world/asia/la-fg-south-korea-ferry-20160415-story.html

[2] Bessel Van Der Kolk, The Body Keeps the Score, Viking, 2014.

[3] See Judy Van Zile, Perspectives on Korean Dance, Wesleyan University Press, 2001, p. 85, for an explication of various methods of sleeve manipulation (and differing qualities of the sleeves in terms of fabric and length).

[4] Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others, Picador, 2003, p. 117.

[5] The civil trial related to the 22nd and Market Street tragedy was just getting underway as this essay was being completed, in mid-September, 2016.