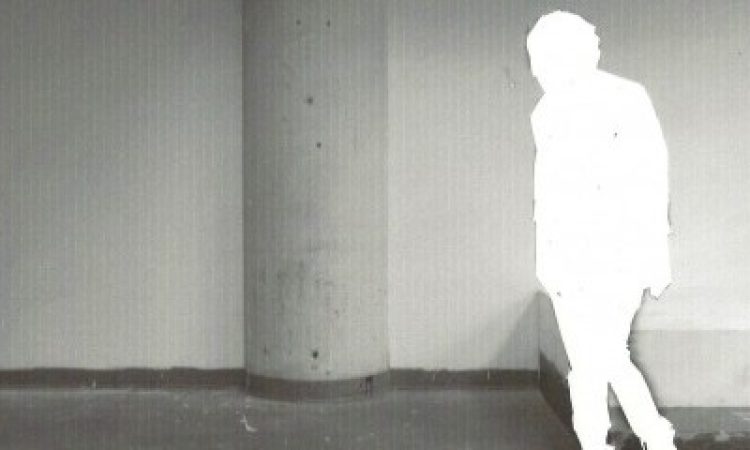

In the whitewashed, post-industrial lobby of Vox Populi, Meg Foley exposes something about time, chipping excess away from essence.

The undergird (the title is not capitalized) begins with a series of tormented spasms, frozen in time by long, tenuous holds. On the raw wooden floor she executes a continuous loop of stillness, then spasm, then stillness—a hold in a clenched position.

She is convex, lying on her side with her back extended, as if her spine has been gripped by some outside agent, a fist clenched tightly under her thigh. I count the seconds: one, two, three, four.

Then, suddenly, she is on one bent knee, the other leg taut and extended to her side. Her expression is one of inward attention: wide, straining eyes, but flat-faced and unemotional otherwise.

Vox’s walls are painted white, and above, the ugly cables and ceiling infrastructure are concealed by simply painting them, too, white. It hides. White noise—cars passing on the wet road outside, and viewers shifting their weight on the creaky wooden floor—is the undergird’s soundtrack. This quotidian frame exposes Foley, in her sweater and jeans, sweating and showing her effort in each twisted plank.

Time is a brittle substance held together by rusted wires. Foley’s spasms bob, isolated, on a strand like beads on a necklace.

Foley said ages ago that she believes in art that is interactive in that it “inspires you to notice time passing.” I become attuned to waiting, studying each crooked limb. And then Foley introduces a new kind of time, lying on her back with her arms above her in a loop, a ballerina’s first position. Rather than holding them, she gradually brings them down to her chest.

Now she scrambles to her knees with arms extended in front as if to catch her impending fall, then freezes. Very slowly, very slightly, she pitches forward. I might not have caught this soft motion before, or would have thought it was an accidental adjustment. The beads shift along the wire.

Later, the form of the dance changes abruptly. In the spasms, her attention was inward, on the subtlest motions of her own body, and on her relationship to the floor; now, she attends to the entire room.

Her gestures are quick, geometric, and rapidly following one upon the other with no breaks. She taps her chest, hip, and knee in quick succession. Crossing from one corner of the room to another, she opens her arms to the ceiling, then to the ground behind her, then to the ground in front of her.

Sometimes gesture bursts outward from her body: she leaps toward a column and, forearms vertical in front of her face, rapidly pumps them up and down. Her body rarely flows, it always cuts or drives. When she crosses the room, her arms extended and tense, each step is a march, a straight line, crooking her arch into a many-sided polygon.

If she wanted this to be about her skills as a dancer, she could add grace, rub away some of the effort, attempt virtuosity. But the framework—the “undergird”—is what this piece is about, and it is visible everywhere.

Foley asks for a volunteer. She leans forward and whispers instructions into the volunteer’s ear. She does this again. She does this again. Then, the volunteer says, “I need you to feel the space between my eyes.” Then she again leans forward to whisper. The volunteer says, “I need you to feel the space inside my mouth.”

This is all the volunteer does, and then she goes back to her seat. Its purpose is transparent: Foley gives voice to her piece and the questions it poses. Yet the whisper, the silence, the transmission of unheard words, add a visible but unclear framework.

Foley sets up a projector. It casts a page of her writing on the wall for a few moments, giving a reader time to read maybe four sentences, then she takes it down. She does this with a second page.

Time is not a wire, and we cannot follow it back to the last bead. The message was on the page, but we could not read it all. In the same way, her motions are fleeting. Time passes, and it is behind us. We are at a new motion. Her dance both generous and private. It is literary, rational, literal—she either is doing what she narrates, or she is not doing what she narrates. And she gives herself up to time: we either saw that, or we did not.

The undergird, Meg Foley, Vox Populi, November 4th, 6th, & 19th, & December 2nd & 18th, voxpopuligallery.org/calendar-event/meg-foley-the-undergird/.