This week, the Stephen Petronio Company took the stage at the Joyce Theater in Chelsea for the twenty-fourth consecutive year. Not surprisingly, the company seemed at home, enhancing the theater’s intimate atmosphere (I am always surprised that, despite the Joyce’s fame as a presenter of dance, it is quite small, with halls that lead right back to theater doors and a tiny downstairs lobby). Merce Cunningham’s Signals (1970), the first work presented, was part of the Petronio Company’s Bloodlines, a five-year project celebrating postmodern dance in America and Petronio’s own lineage as a dancer/choreographer. The Cunningham work was followed by Petronio’s Wild Wild World and the premiere of his newest work, Hardness 10. The company members were at their best when performing Petronio’s swirling and punctuated contemporary style, and seemed less comfortable in Cunningham’s more linear vocabulary.

But they worked hard in Signals. The soloists and duet that opened the piece grappled with the stark vocabulary of precarious balancing shapes and quirky linear shifts of weight and level. As a dancer, I understand how difficult unadorned movement can be; this was no exception. The dancers searched for clarity in movement that lacked the extra fanfare of their usual vocabulary and training. It led me to wonder if they had taken Cunningham classes regularly during the rehearsal process, and to miss seeing a company of dancers trained deeply in the Cunningham style. Petronio’s dancers also faced the audience presentationally, as they often do in his work, suggesting an outward focus rather than the inward intention that grounds performers in this rigorous style. The second soloist, Bria Bacon, a recent Rutgers graduate (joining two other Rutgers grads in the company), held her own; I trusted her as she leapt into solid landings and perched into a prolonged tilted balance with fully extended leg. Her confidence in her solo and in ensemble work created a sense of play.

One of the stranger moments in the work came with the addition of a long bamboo pole during the trio, like something out of a space-age Morris dance. The dancer wielding the pole seemed like an old-school ballet master measuring out lines in space, slicing between the duet dancers. The costumes (by Cunningham, reconstructed by Jeffrey Wirsing) were also curious—black strapping wrapped around cotton sweats, like a long tourniquet—as was the electronic music, curiously beautiful, played live by Composers Inside Electronics. The strongest part was the ensemble section when dancers took turns changing places in line while holding up numbers and deftly executing a series of petite allegro jumps (temps de cuisse followed by assemblé for you balletomanes out there).

Petronio’s Wild Wild World, an excerpt from the 2003 Underland, was presented in full at the Joyce in 2011. Here I could see what the dancers had been training for: balletic vocabulary infused with hip circles, head swirls, and arms sequencing out from the upper back like flares. The dancers seemed totally at home in their costumes—edgy ripped black tops with tight shorts—and in the movement, taking risks, having fun, working together, and even showing off. The piece’s complicated phrase-work was non-stop—my companion noted that the dancing was “at a constant 10”—and ended with a staccato solo for Jaqlin Medlock at almost fast-forward speed.

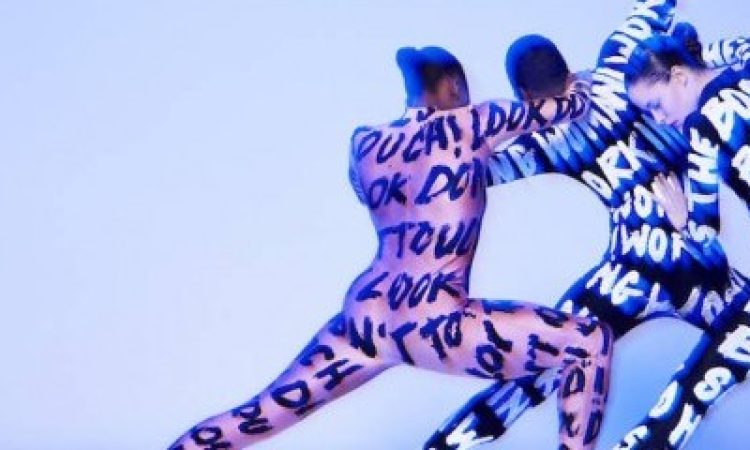

Hardness 10 began with lights, like seven moons, above the stage and one spotlight on musician Liam Byrne, playing a score by Nico Muhly (his third for Petronio). The back curtain was opened to reveal a brick wall, and Petronio gave us a while to take it all in, while the dancers shifted in a repeated walking pattern. I appreciated this simplicity, especially in contrast with the costuming. The black and beige unitards featured splashy text, #metoo slogans such as “Her story!,” Working woman,” “Look don’t touch,” “Read my Hips,” and “She’s the Boss.” Many audience members I spoke to after the performance talked about concentrating on trying to read and understand the texts. As the group continued to shift, a soloist would surge out of the group for a quirky whirling solo and then return so that the spacing of the group organically opened. More relaxed vocabulary mingled with the athletic swirling, leaping, punctuated arms, and beaten jumps. The four female dancers emerged from the group in strong duets, with a particularly arresting (and uniquely slow) moment as one woman wrapped her hands around another’s lower back. When the men came in to block them, the women rushed around to the front, the men framing them. This moment emphasized that, until this point, the men had been favored, especially Nick Sciscione, Petronio’s assistant (and for good reason, as he excels at the detailed phrase work). The women ended on stage by themselves, and though the program note referenced the rendering of a diamond, the women’s ending move, with fists high, held clear and timely meaning.

Stephen Petronio Company, March 20-25, The Joyce in Chelsea, https://joyce.org/performances/stephen-petronio-company