“How do you frame 20?” One of Philly’s long-standing dance companies, Subcircle, provocatively asks itself this question as it celebrates 20 years of art-making in Philadelphia this month. I sat down with the three co-directors—Jorge Cousineau, Niki Cousineau, and Scott McPheeters—to hear their reflections on two decades and what’s next.

Jorge Cousineau: “We wanted the audience to find their way into the basement … to turn on other sensors of what could have happened here?”

In 1999, Subcircle was the name of the second piece Jorge and Niki co-conceived. In the basement of Trinity Center for Urban Life at 22nd and Spruce Streets, audience members walked through a tunnel filled with original music, as pod–like installations guided them to the stage. The stage performance included wheeled booths in which the dancers pulled themselves on and off stage. Narratively, the show pertained to circus performers in a dystopic future. The performers inhabited the church’s cavernous basement, unaware that their artistic collaboration was birthing the framework of Subcircle. Their process—informed by space and engaging site in performances—led them to take this show’s title as their moniker.

Niki Cousineau: “Making installations … was a vibration of excitement of where we wanted to play. [The piece Subcircle] was the prologue, but fed our future work of inhabiting spaces.”

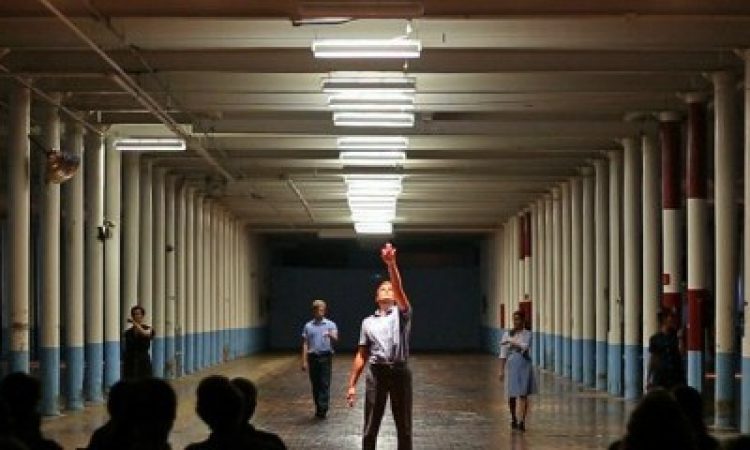

Christy Lee, Scott McPheeters, and Niki Cousineau in Forget me … forget me not. Photo: Commotion Festival.

Subcircle characterizes their process as “mining,” predominantly creating in site-specific locations. Niki notes her affection for crumbling spaces. With each show she mines the location’s unique tones “receiving what they (the sites) are saying.” In Banking Hours (2000), they transformed a former bank at 2nd and Girard; in Forget me … forget me not (2012), they embodied the top two stories of Shiloh Baptist Church at 21st and Christian.

Scott McPheeters adds the importance of “opening my eyes to all the different bodies that have existed in a given space.”

With Subcircle’s arrival, Forget me … forget me not invited audience members to discover the “forgotten” space of Shiloh Baptist. Created in partnership with the Commotion Festival, the dancers moved like ghosts within this immersive project, guiding and allowing audiences to wander through the site’s majestic architecture. The choreography directed audience members’ attention to the historic site’s high ceilings, odd corners, and exposed brick.

SM: “I was caught in the cycle, guiding people through a memory.”

NC: “I want to be in a space and see it from a different perspective or how I could have someone else’s point of view.”

As a multidisciplinary dance company, Subcircle entwines choreography, installation, and film. Their 2010 production of Only Sleeping intricately choreographed live performers and filmed action. It raised questions about absence and togetherness, as the artists were challenged by collaborator Geoff Sobelle. They initiated rules of engagement, emailing prompts to each other, directing attention to a chair, the ceiling, a radiator—objects of a particular filmed space.

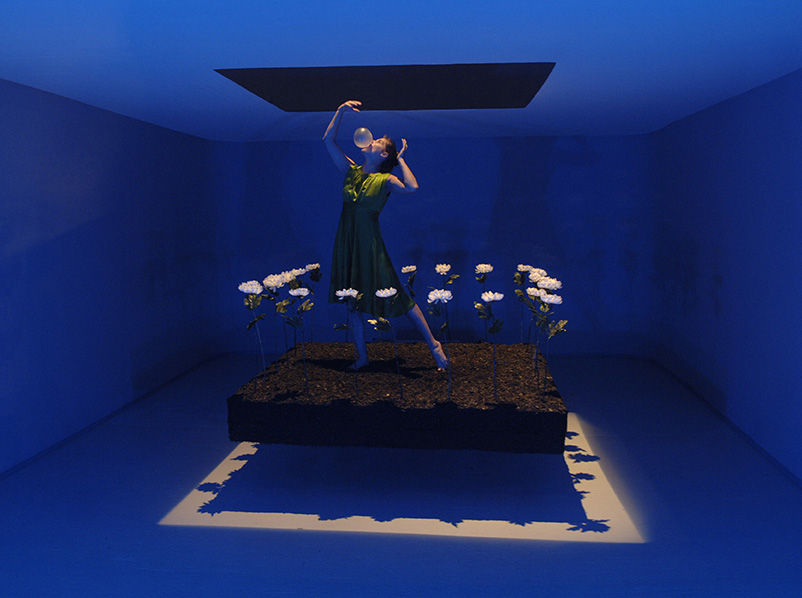

Christy Lee in Still Unknown. Photo: JJ Tizou.

Jorge recalls Still Unknown (2006) as “one of the most ambitious projects we made.” They transformed the giant warehouse of Icebox Project Space by dropping its high ceiling. Scott notes, “Each dancer and choreographer got to curate their own space.” The epic installation (the space was half a football field in size) was chopped up into installations inspired by the provocative question, “What do you still not know?” The space magnified each artist’s response of seven-minute short takes, which the audience, in two groups, wandered through.

In Here (2008), Jorge notes, “The camera feels like another dancer.” Acknowledging the scale and energy of Still Unknown, the film Here is intentionally small and lasting. With film, the creative team could flip, reposition, and re-sequence spaces, time, and movement, initiating new discoveries. Noting the duality of these artist worlds, Jorge remarks on the creative difference of the seen and unseen in film versus live performance—“what an inner world looks like to someone, as opposed to what everyone else seems to be seeing.”

Geoff Sobelle and Niki Cousineau in Only Sleeping. Photo: Jorge Cousineau.

In 2014, when the three artists co-purchased a farm in Biddeford, Maine, long-standing collaborator and choreographer Scott McPheeters joined Subcircle as co-director. For years, the three had bantered over a pipe dream of owning a space and creating an artist residency together. On a family visit to Biddeford, where Scott grew up, his parents told him about an old plant nursery up for sale. Scott grasped the site’s possibilities, and Niki drove up to see the property. They co-purchased the four-bedroom house, the barn, and nine acres, and Scott formally joined as co-director of Subcircle.

Months after purchasing the farm, they shot their dance film Here nor there (2014) in Biddeford. It manifested a dream for Scott: “I could transpose this Philadelphia community to this place where I grew up.”

For four years, they worked on the farm to create a long-imagined artist residency. This summer (starting July 1) marks the first two artists-in-residence with choreographers Laura Petterson and Beau Hancock receiving a fully funded, ten-day retreat. At the end of their time they have one open-ended “interaction” with residents of the small town to share their artistic processes.

Given this work and the company’s focuses, Niki asks, “How do you use your body as a piece of the landscape? Then take that experiment from the outdoors and bring it into the studio as material.” According to Scott, “We are interested in spaces that are in transition. We are a company in transition.” Subcircle is testing the balance between their performances and managing the farm and residency program. They note that only 10% of all artist residencies in the country are for performing arts. They are creating a program invested in bringing Philadelphia artists to Biddeford with ongoing subsidization.

For this month’s celebration, Jorge used his own customized software, Self Edit, to create an installation. With six projectors, the program randomly selects 15-second clips from each project in Subcircle’s 20-year history. Self Edit’s surprising mash-up of their artistic vision frees the artistic directors from a personal dissection of the company’s work.

Jorge identifies a part of their ongoing mission as “seeing something that hasn’t quite lifted itself above the surface.”

Subcircle’s most recent show, Hold still while I figure this out (2017), was a response to current social, political, and economic issues: “How do we make another world?” But what they discovered, Scott notes, was complicated: “you can’t build a world without the memory of what used to be there.” The sites, the spaces, and the projects keep layering upon one another.

How do you Frame 20? Subcircle. http://subcircle.org/