Arts educator, former dancer, and writer Phil Chan has advised prominent ballet companies on removing derogatory representations of Asian people from their productions; however, he doesn’t want to be the sole “Political Correctness Police.” With his book, Final Bow for Yellowface: Dancing Between Intention and Impact, Chan provides a guide to identifying and correcting offensive cultural depictions in performances. In detailing best practices, Chan empowers ballet lovers and newcomers to join him in giving this classical art form a more inclusive future.

Chan’s book chronicles his work from 2017, when he and New York City Ballet soloist Georgina Pazcoguin founded Final Bow for Yellowface, an advocacy organization that encourages ballet companies around the world to make this pledge: “I love ballet as an art form, and acknowledge that to achieve diversity among our artists, audiences, donors, students, volunteers, and staff requires inclusion. I am committed to eliminating outdated and offensive stereotypes of Asians (Yellowface) on our stages.” Today, more than 80 dance and other arts leaders have signed it.

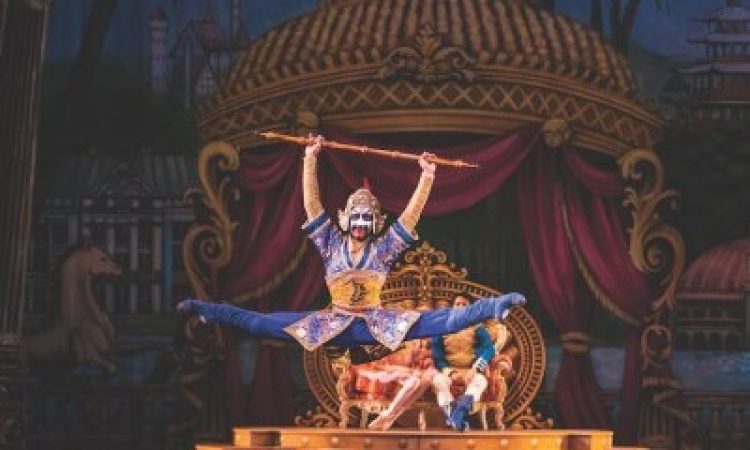

Final Bow for Yellowface consists of ten chapters which explore the pledge in practice. The first section focuses on widespread changes made in 2017 to The Nutcracker’s Chinese Tea dance. Initiated by New York City Ballet‘s decision to revisit the scene, and further fueled by the Final Bow for Yellowface pledge, ballet companies across the nation revised the well-known choreography, costuming, and makeup. Examples of problematic representations included exaggerated servile movements, rice paddy hats, queue wigs, painted slanted eyes, and “Fu Manchu” mustaches. Chan references various companies’ revisions to illuminate how two-dimensional caricature can be turned into dynamic character.

The second section of the book focuses on Chan’s 2019 work with Ballet West as they revived Le Chant du Rossignol (“The Song of the Nightingale”). This abandoned ballet from George Balanchine’s early career tells the story of an emperor and takes place in an exoticized China, which would have captured the imaginations of white ballet-goers in 1925. Since the show never reached public eyes, some members of the creative team felt immense responsibility for honoring Balanchine’s original vision. Others prioritized contemporizing the work to reflect current understandings of Chinese culture and to avoid isolating modern audiences. Reflecting on this experience, Chan shares lessons on navigating from appropriation towards appreciation.

Using colloquial, lighthearted language, Chan writes an accessible book that invites everyone to join the conversation. He includes relevant context on ballet and Asian history so that dancers and non-dancers alike, as well as those less familiar with the Asian-American experience, have a baseline level of knowledge for approaching both subject areas. Chan also urges readers to form their own opinions by respectfully presenting multiple perspectives. On one end of the spectrum, traditionalists resist change, fearing losing their favorite works and believing older ballets should be appreciated through the lens of their historical context. On the other end of the spectrum, some new audiences see these works as colonialist productions with no place in today’s society and support their complete elimination from the canon. In the middle, Chan believes elements of a production can be updated to resonate with modern audiences.

Though dealing with controversial portrayals of race in ballet, Chan never once calls anything or anyone racist. He completely avoids finger pointing, blaming, and calling out. He instead opts for more positive and potentially productive language, reframing the discussion to be about “intention” and “impact.” Knowing injury is usually not the artists’ objective, Chan argues that removing insensitive racial and cultural representations closes the gap between the artist’s perceived intention and the art work’s real impact. The work then becomes more successful at achieving the artist’s goals and captivating the audience.

Chan provides two tools to help artists and audiences evaluate intention and impact. The first is about identifying elements of caricature and understanding their purpose so that fully formed characters can be developed. The second is a “cultural integrity grid” that helps determine whether or not a work might be problematic. Chan emphasizes that the end goal of eliminating demeaning stereotypes should not be political correctness but higher quality art: “Avoiding giving offense is also not a very powerful artistic motivation—the creation becomes no longer something offered with pleasure but something offered with trepidation, to placate rather than to freely share something beautiful.”

Though Chan effectively describes the before-and-after difference in revised ballets and draws from other art disciplines to illustrate his points, I wish visual examples were provided along with the text. Descriptions are detailed, but aspects of dance are inevitably lost when translating movement onto paper. Nevertheless, weaving personal anecdotes with solutions-oriented exercises, Chan’s book is informative and practical.

The historic portrayal of individuals as “other” onstage has an undeniable long-term impact on both minority and majority groups. The feeling that certain people are not like everyone else persists, consciously or subconsciously, long after the theater curtains fall. Though Chan focuses specifically on Asian representations in ballet, his experiences and lessons are more broadly applicable. Looking closely and questioning what we see on stage is a small step toward creating art that is diverse, vibrant, and all-around better, leading to more inclusion in the dance world and beyond.

Phil Chan, Final Bow for Yellowface: Dancing Between Intention and Impact. Brooklyn, NY: Yellow Peril Press, 2020. e-book.