What a gift, in this year cluttered with losses, to receive a work from beyond the grave. Dance We Do: A Poet Explores Black Dance is a posthumous book by Ntozake Shange that brings together personal reflections and interviews with dance luminaries in order to chart the landscape of Black dance in the United States.

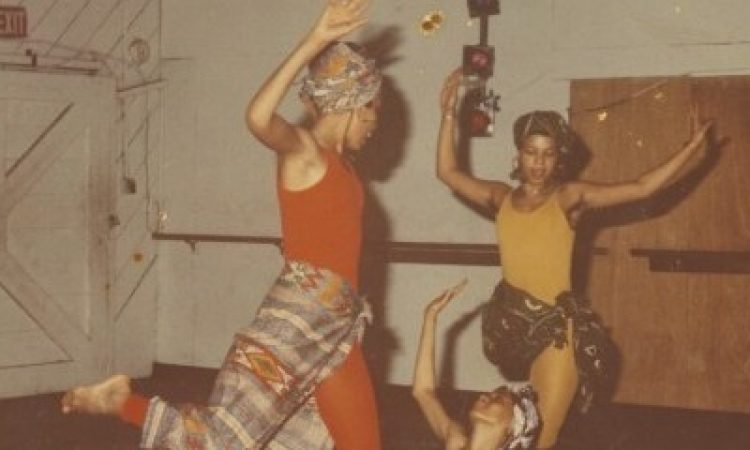

Shange was a prolific poet, and she is still best known for her choreopoem For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide / When the Rainbow is Enuf. But Shange was also very much a dancer, even before she became a writer. In the essay “Dance in My Life,” Shange recalls taking ballet from kindergarten to high school, where she was consistently made to feel excessive and out of place. Later, she was able to find true fulfillment in dance by connecting with the Black Arts Movement. In this new context, Shange writes, “I was re-made.” Shange went on to take classes all over New York and San Francisco, and to dance professionally with artists such as Halifu Osumare, Raymond Sawyer, and Dianne McIntyre, all of whom are profiled in the book.

Dance We Do is all the stronger for having been written by an artist who was so thoroughly immersed in both language and movement. It is unsurprising that this iconic author offers richly poetic descriptions of bodies in motion: she imagines dancers as ocelots and herons, legs as telephone poles and redwoods. But it is rarer to find profiles of dance artists that are written from within the studio. Rather than review famous performances, Shange takes readers through the sweaty rituals of class and rehearsal. She expresses the challenge and joy of Ed Mock’s work through the memory of lightheartedly wiping out during grand allegro, and she introduces Dianne McIntyre amidst the ricocheting nerves and uncertainty of an audition. The familiarity of these anecdotes to dancers and dance makers offers an important corrective to historical narratives that operate at a far remove from the embodied realties of dance.

In addition to providing an intimate perspective on other dance artists, Shange’s relationship to movement results in an understanding of language that rejects divisions between mind and body. For Shange, writing and dance were inextricably entwined, with words and gestures constantly informing one another. It seems that poems would often percolate while Shange was dancing—in one humorous scene, she recalls being chided by Eleo Pomare for letting her mind wander to poetry while lying on the floor doing core exercises. But even when writing, Shange was fully embodied. In the afterword, performer and theater professor Reneé L. Charlow shares that Shange would often sweat while she wrote because the process was taxing on a physical as well as a mental level. Perhaps most stirring are Shange’s descriptions of collaborations in which movement and language co-evolve: “on her own, in silence, [Mickey] Davidson can seduce a word from me, propel an image out of my mouth, that is a secondary clause to her movement. In other words, Mickey’s dance can create the space for language, so that the movement precedes the language and creates a space for words.”

But Dance We Do gives us more than a portrait of Shange’s process, or even that of her collaborators. The book’s series of profiles closes with an eye towards the future in interviews with Camille A. Brown and Davalois Fearon, choreographers who Shange never worked with directly but who are important figures in contemporary dance. And the echoes of history reverberate throughout the profiles as well. The legacy of Katherine Dunham surfaces regularly, and Shange prompts her interview subjects to reflect on their engagement with the long lineage of Black dance. Artists grapple with minstrelsy, for instance, or find inspiration in the Silver Belles, a group of Black chorus girls from the ‘30s and ‘40s. Given how long the contributions of Black artists have been excluded from histories of dance, no one book will be able to repair this erasure. Still, Dance We Do is an important addition to the archive, recording recent memories and giving under-acknowledged histories the attention due to them.

If there is something wanting in Dance We Do, it is that the book is only an enticing taste of what was clearly intended to be a longer project. A slim volume at only 160 pages, Dance We Do was cut short by Shange’s illness and untimely death. In fact, much of the writing in the book is transcribed from conversations between Shange and Charlow, conducted after two strokes made it too challenging for Shange to type. The resulting language is casual and accessible, made more so by a glossary that defines technical and historical terms.

Whether or not one approaches the book with a background in dance or poetry, Dance We Do offers an expansive portrayal of Black dance and a nuanced example of this artist’s approach to writing and movement. Even after her passing, Shange continues to allow limbs to speak and words to dance.

Ntozake Shange, Dance We Do: A Poet Explores Black Dance. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2020. 160pp.