Don’t Stop ‘Till You Get Enough: Detroit, Jackson, and Racialized Economies

by Leilia Mire

How do performance studies teach us how economies operate? How is racialized capital created, (re)created, and maintained over time? How are Michael Jackson and Detroit quintessential representations of America’s shifts from industrialization, deindustrialization, and its current financialization?

Judith Hamera’s Unfinished Business: Michael Jackson, Detroit, and the Figural Economy of America creates a compelling and thoughtful analysis toward figural economies and their explication through performance. Figural economies (a term coined by Hamera) refers to how circumstances, figures, places, and/or individuals can be used to represent economic patterns. Using performances by and about African Americans from the 1980s to present day, Hamera highlights the inseparability of race and capitalism. She clearly lays out how performance is “affective and affecting: both reflecting and shaping the ways liminal periods in capitalism feel in the body and in the public sphere” (p.xi). In doing so, she brilliantly presents transitional periods in capitalism as symptomatic and representative of performance in structural economies.

Hamera, a professor of dance with affiliations in American studies, gender and sexuality studies, and urban studies at Princeton University, uses performance practice to research economic challenges and periods of structural change. As a native of Detroit her thorough investigation of the city’s economic fluctuation is adept and well-credentialed. Perhaps most notable is her ability to marry performance studies and economic theory to represent racialized labor and the decline of deindustrialization.

The book is in two parts. Part one presents Michael Jackson’s life and career as an example of industrial and post-industrial figural economy. She investigates Jackson’s figural potential as a reflection of Detroit’s economic decline despite the systemic mechanisms that have aided in his racialized invisibility as a human motor. Jackson is transformed into a figure struggling for financial redemption in an economy where “enough” is never enough. The robust material is an illuminating read for economists and performance artists alike.

Hamera demonstrates racialized figural economies in a number of ways. For instance, Michael Jackson’s career was managed by his father, Joe Jackson. Joe, a former factory and steel worker, abandoned his dreams of becoming a professional boxer and succumbed to Industrial Era racialized labor exploitation. Joe raised young Jackson under the same stringent conditions he was exposed to as a Black child laborer. As demonstrated by the rise and fall of the automobile industry, Michael Jackson’s career parallels Detroit’s story of racialized labor practices followed by overconsumption, debt, uncontrolled finances, economic deterioration, and a posthumous return to the public as a laboring victim. Jackson is driven to collapse by a system that exploits, overworks, and perpetuates racial inequity. Jackson, like Detroit could never get enough because capitalism was built to perpetuate a false reality where “enough” was unattainable.

Unfinished Business’ focus on Jackson articulates how race and capitalism are intertwined. Too often scholars exemplify deindustrialization through white figures (think John Travolta in Saturday Night Fever); Hamera tackles it head on without whitewashing Detroit’s economically racialized identity. Posturing Jackson’s performance career amidst historical accounts of the United States Steel Industry illuminates how bodies are not treated the same. She even accounts for Jackson’s disheartening mental collapse during the This Is It tour and his uncomfortable backstage relationship with President Reagan. Hamera treats Jackson as a transitional figure, revealing a cautionary tale of deindustrialization.

Part two impressively unpacks the ideas promoted earlier through analysis of plays and public art projects. It opens with an investigation into Detroit’s racialized identity through Lisa D’Amour’s Detroit, Dominique Morisseau’s Detroit ‘67, and Berry Gordy’s Motown, the Musical to study the intersections between race, place, home, and work. Hamera’s selections address multiple interpretations of Detroit; she uses the plays as a “synecdoche not only for deindustrialization but also for the multisystem failures of late capitalism” (p.106).

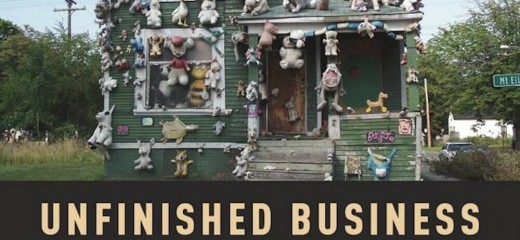

The final chapter dissects Detroit’s supposed renaissance and civic revival under the guise of “kunst washing” (“art washing”). This neoliberal practice encourages people to invest in the city through creativity while framing the city’s large Black population as creatively incompetent and in need of salvation by economic elites. This perpetuates privileging private capital over state investment, thus allowing politicians to use outside artists to erase the city’s history. These ploys are juxtaposed by Tyree Guyton’s The Heidelberg Project and Mike Kelley’s Mobile Homestead, two local public art projects that aim to acknowledge the memory of Detroit that politicians are so eager to forget.

This book is an essential read for scholars, economists, and performance makers. Its ability to contextualize economic patterns through the lens of performance studies underscores the significance of intersectional studies. In doing so, it reminds readers of the complex economic systems at play and the unfinished business that has yet to be done when “enough” is just an illusion.

Judith Hamera, Unfinished Business: Michael Jackson, Detroit, and the Figural Economy of America. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

By Leila Mire

January 14, 2021