The multidimensional film, Revivals of Blackness, felt like an endless embrace from nurturing, ancestral arms. As an African American woman and mother, I felt seen and celebrated all at once. Conceived and choreographed by Lela Aisha Jones with beautiful cinematography by Aidan Un, the film is a journey of defining what it means to be Black as self and as community.

“Stop interrupting me from being black!” Lela Jones begins boldly in a close-up of her face. Flash to the face of jazz pianist Luke Carlos O’Reilly, eyes closed, listening to Miles Davis. Another flash and the first scene, Breathe, introduces movement artists Peaches Jones and Fyness Mason, along with Lela Aisha Jones. They sit on the ground in an open, empty indoor space. Lit candles surround them, as they gather what looks to be grass. Lela Jones, whose voice is the soundscape, speaks about her African roots. All three women work in unity. I read their silent labor, accompanied by the look of gratitude in their eyes as a representation of the vastness of Mother Nature. This reads as a ritual, a form of worship to the ancestors.

In an interlude, Alex Shaw, musician and husband to Lela Aisha Jones, speaks about how Blackness took care of him, especially in Black women. Shaw’s passion for this film is a way to reciprocate the love he experienced from the women in his life. We see Lela Aisha Jones frolicking in the ocean with her son, Makailin Waiyun Shaw, to the soulful sounds of the jazz band. This moment is like a sweet love letter to all Black mothers.

The Aluta Sempre scene draws me in with Shaw playing the Berimbau as he sings passionately and intently. Soon Leila Aisha Jones joins in singing, followed by the band playing with distinct Brazilian rhythm and fluidity. Layered in the background, we see people perform Capoeira in different authentic, Brazilian settings. Warm images of rhythmically changing geometric colors and shapes are superimposed and blended with the video in a hypnotic pattern.

Next interlude, I am quickly transported from celebratory thoughts to dark realities. Through an eerie black and white filter, I see Lela Aisha Jones hold her young son, repeatedly singing into the camera, “Please, don’t kill Black people.” The next moment, her little boy is dancing around her by the ocean while she also dances joyously and freely. The voice of Sanchel Brown emerges, poetically speaking about Black sons not being safe in the world. The musical score fills me with layers of instrumentation. Towards the end of this section, a silhouette of a womanly figure is left standing by the ocean with fabric hugging her body as it blows in the wind. She is now alone, a childless mother. I am boldly reminded that Black lives do matter.

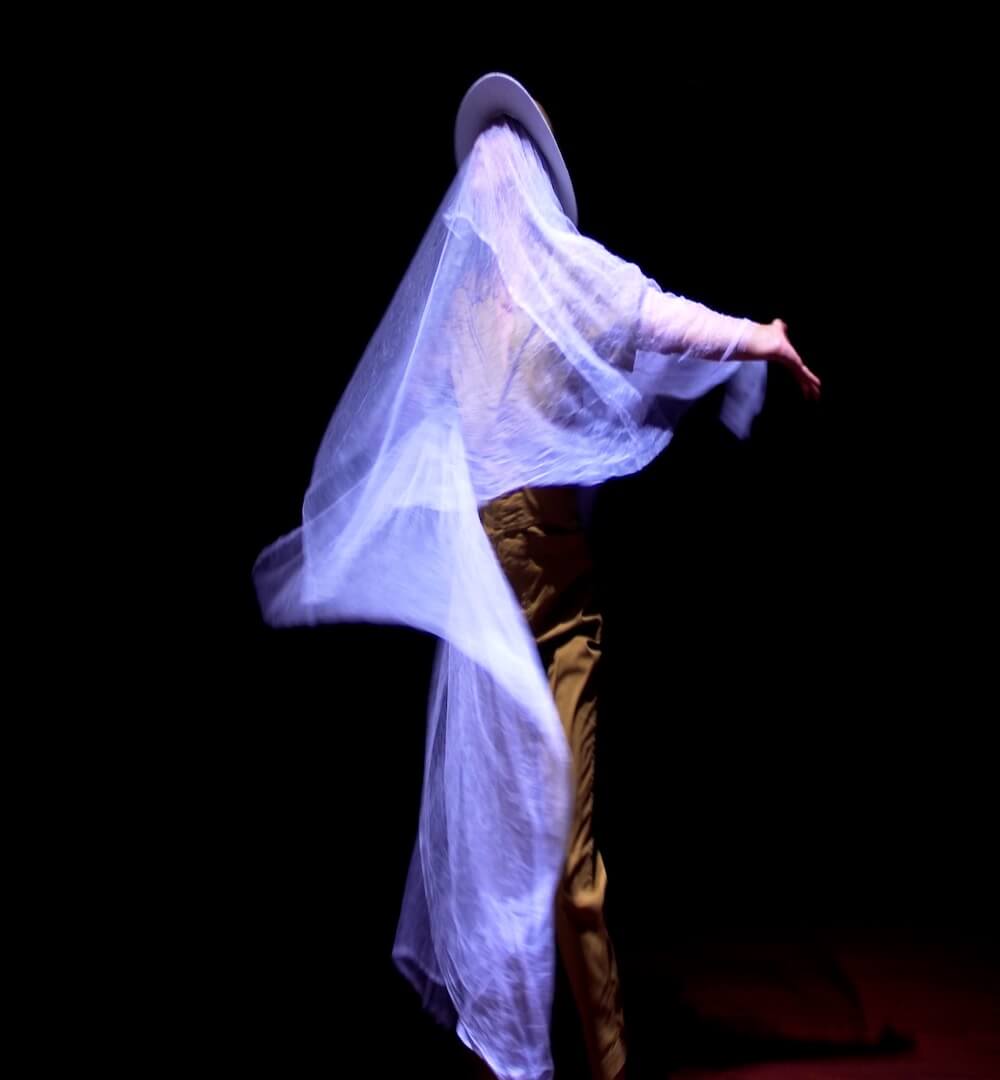

Though the film is sturated with resonating movement, the two dance-centered scenesCan’t Breathe and Black Joy are most captivating. In Can’t Breathe, O’Reilly and Lela Jones share how the Black church was one of the few spaces where movement and physical expression was allowed. Here, Jones is accompanied by the same two dancers from before. Sitting in chairs, with gloves resembling those worn by Baptist church ushers, they contract their torsos, open and gather their arms in an unspoken welcome. When they stand, they continue in an African vernacular weaving around the chairs. All three jump, praise and shout using their bodies as images of worship. One dancer is draped over the head with a long white fabric topped by a hat – a hidden, faceless figure. The combination of violin and trumpet carries over the piano, drums and bass, igniting movement inside me. This scene ends with Lela Jones laying on the ground, back arched, looking upside down into the camera. Hung. That image alone evokes thoughts of being lynched. It makes me want to take a pause and reflect on the range of lineage encompassing both good and bad things.

I wish Black Joy could be the final scene, because of it’s hopeful conclusion. The band’s playful instrumentation follows the spontaneous travels of little Shaw. The music captures his uninhibited dances down the sidewalk. Walking to his own beat, he sporadically breaks out into skipping, spinning and running along his own winding path. I want to run with him! Watching him makes me reminisce about my own childhood as a young Black girl and how everything in the world around me seemed possible and tangible.

Revivals of Blackness encapsulates so much depth that it would have to be viewed multiple times to ingest all of the beauty that it possesses.

Revivals of Blackness, World Live Cafe, June 3rd and June 6th.