Juan Felipe Miranda Medina, a musician, dancer, and researcher from Arequipa, Peru, specializes in the step dance zapateo. The focus of his artistic and scholarly work is Afro-Peruvian music and dance. Medina is the first participant in thINKingDANCE’s “Decolonizing Dance Writing” series. Following this interview is a workshop on July 17th, along with a piece detailing Medina’s work on decolonizing dance.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

MIRE: What drew you to this project, and how does it speak to you?

MEDINA: I became curious about “decolonization” after reading about it somewhere. While the term “decolonization” is popular in the West, its discourse does not exist in the same way among Peruvians outside academia. Latin American scholars propose “coloniality” and “decoloniality” as alternate frameworks. An investigation of decolonization should be situated and grounded in a specific reality that cannot be applied universally because colonialism shows up in our lives differently.

I do think that decolonization speaks to identifying the roots of dances like zapateo and recognizing that they have been shaped by colonization, geography, and time. I am interested in how the theory of decolonization can inform dancers to make themselves more reflexive surrounding power within their practice.

MIRE: How has colonialism’s legacy in zapateo informed your movement and teaching practice?

MEDINA: I use various frameworks to reflect how colonial structures pervade my work. I insist on knowing a dance’s history and aesthetic before adding to it. In efforts to challenge conventions, I work to understand dance through a scholarly lens as well as through an embodied practice. Decolonizing work does not make sense to me. I’d rather put my efforts toward moving the dance forward.

While the knowledge our ancestors hold is pivotal, we should not keep our ancestors’ dances frozen in time. For instance, zapateo (a predominantly “male” dance) is beginning to have more female performers. That’s wonderful and needs to be part of the decolonizationist agenda. Decolonization doesn’t mean returning to other oppressive power structures. We need to actively advance the craft by decentering the people who have held power for so long. As a term, “decolonization” is insufficient because it sounds as if we are trying to remove colonization which is impossible. However, if we define it as an act of empathy and the pursuit of justice, then we have a path forward.

MIRE: While decolonization resonates with many people in the United States, I don’t know that the term has a clear direction. As you allude to, decolonization involves the liberation of spaces through challenging dominant power structures but when we consider the consequences of systemic erasure, how do we return to a place we might have never known? How do we go back to something from our ancestry in an authentic way without idealizing a version of it that is a farce or lacks nuance?

MEDINA: I see this often. You have people like Nicomedes Santa Cruz and Victoria Santa Cruz who are influential Black dancers and musicians with strong western backgrounds. Victoria has a theory of ancestral memory (memorias ancestrales) that she applied to the choreography of a dance called, ‘Lando,’ which according to Nicomedes had been lost. She asserts that her ancestors cultivated rhythm for centuries. Those rhythms continue to live in the Cosmos and she can connect with them. Her theory would later extend to the belief that all people can connect with them. In the revival of the landó and other dances, some elements of the music and dance were changed. This is part of giving life to a practice but it is also important to exercise awareness while balancing innovation and tradition.

MIRE: We spoke about the tendency for movements to lose direction because of too much emphasis on praxis from outlined theory and vice versa. I’m curious to know what you’re hoping to gain from the Decolonizing Dance Writing International Exchange Program and how we can decolonize dance and dance writing without it being co-opted into a buzzword.

MEDINA: Decolonization is an inherently political concept and dance must play a part in it. We need to recognize and care about the connection between material conditions and power relations. When the Spaniards first came to Peru and the Americas, they destroyed rituals and religions in order to colonize subjectively and materially. So, we have to find a new value in our dances with pride and joy as we dismantle the narrative that Western dances are the “mother dances” and admit to ourselves that colonization has already happened and cannot be returned to its pre-colonized state. We need to be ethically committed to dance and dance writing that transcends the Western world while being knowledgeable about what we contribute. We need to care. Education will be paramount.

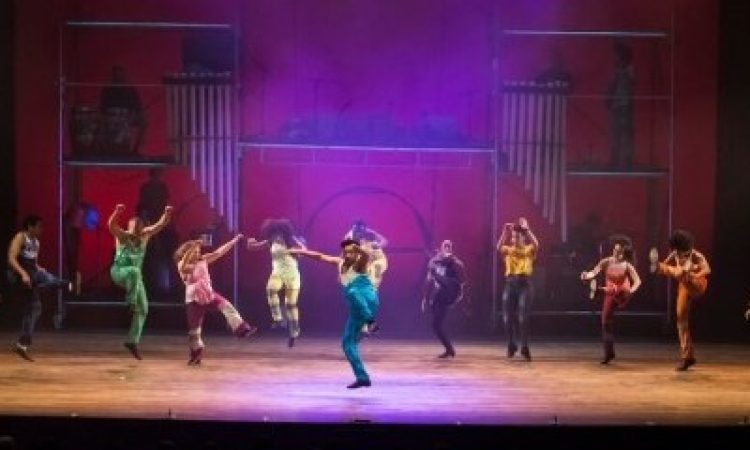

In Peru, there needs to be an increase in dance research not only by scholars, but by practitioners themselves. One group doing tremendous work is Teatro del Milenio. The company was formed in the 1990s and since its inception has explored Andean and Afro-Peruvian traditions while embracing its evolution over time. TEATRO was unique in that it showed us a new way in which theater can use tradition as a point of departure toward a greater expressive power. We need more people doing work like this so that decolonization is present in the rethinking of tradition that transcends placing music and dance genres into limiting boxes.

How do we take action? Being critical of colonialism’s past is not enough. We need to treat decolonization as an act of care. We need to turn to ethics that take action! Colonization was a team effort. For me, decolonization will require solidarity. We have to build communities of artists who are ethically engaged in social transformation. That’s a step towards decolonization.

Decolonizing Dance Writing Workshop, thINKingDANCE, Cardell Dance Studio and online, July 17.

This project was funded by a grant from Critical Minded.