Bringing D-Man in the Waters into the future

by Kristen Shahverdian

After Arnie Zane died from AIDS-related lymphoma in 1988, Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company dancers returned to the studio. In an apparently unusual move, Bill T. Jones told the dancers to improvise, without any prompts besides the music that he turned on. From this beginning, Jones choreographed D-Man in the Waters (1989). If the dancers in 1989 had death, fear, sorrow, and anger to energize their performance, what do 21st century dance students bring to D-Man in the Waters? What motivates them to stay within the unrelenting physicality of D-Man? These questions lie at the foundation of Can You Bring It: Bill T. Jones and D-Man in the Waters, a film by Rosalynde LeBlanc and Tom Hurwitz, streaming through Lightbox Film Center at University of the Arts and other independent film venues across the country.

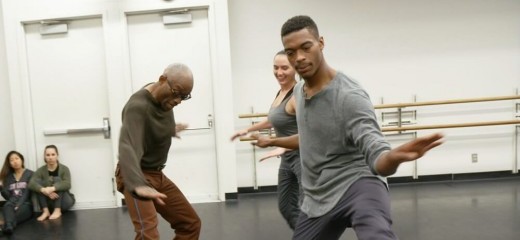

Watching Can You Bring It is part dance history lesson, part advocacy for the power of dance, and part a generational exploration. LeBlanc and Hurwitz achieve these layered themes by flowing between footage of the original performance of D-Man in the Waters, the current company members performing the work, and students at Loyola Marymount University learning the piece. LeBlanc is both the filmmaker and the students’ teacher (as well as a former Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane company member) and the motivation for the film came from her investigation into how students resonate with D-Man 30+ years after its creation. Although we see some of the students in the beginning of the film, most of the first third is devoted to the original company members talking about the history of Jones and Zane, Zane’s death and creating D-Man. The dancers speak about their experiences witnessing Zane’s death and how it felt to be alive and working during the AIDS epidemic. This approach helps me understand not only how the dance’s steps look, but also how they feel and what they mean.

Much of the footage shows constant motion with bodies falling, rolling, diving, and jumping at a super-human speed. A dancer runs onto another’s back and extends her body high into the air, with complete abandonment and the trust that someone will be there to catch her. There is a repeating gesture of arms bent at the elbows, held in front of the face, rapidly crossing the forearms. In many of the clips a dancer is held in the air by partner(s), and the image of swimming returns again and again with arms reaching forward and scooping back and inverted legs opening and closing like breaststroke. In the final image, the last dancer runs and dives onto his stomach-sliding across the stage. It reminds me of a bird flying close to the ocean, wings extended and its belly skimming the water’s surface.

Images from the AIDS crisis, men dying, the protests, the AIDS quilt, move into a scene with LeBlanc and the students where she asks, “what were you told about AIDS?” For these college students, AIDS seems distant, and they speak of learning little about it from school or parents. I became a teenager during the AIDS epidemic and for some of us who grew up in the 80’s and 90’s, death was intricately tied to sex. It was a reminder that our experiences shape us, and if we do not talk about them, we should not assume that a generation who did not have those experiences would know them.

LeBlanc does not patronize the students nor paint them as young people without ideals or drive. When LeBlanc asks them what matters to them, the camera pans to the students’ faces and I see a struggle to answer that mirrors the stasis they describe feeling. LeBlanc asks the dancers to hold hands and pull apart from each other. Some of the dancers lower to the floor and others do not, but all the dancers change; whether they stand or sit, their bodies are affected because they are all connected. Moments like this remind me why dance education matters. The word community comes up often with past and present dancers, but how do you create community? Jones articulates the reality of creating D-Man saying, “There was something to push against.” Or as original company member Seán Curran states, “We talk a lot in terms of a modern dance company about community, and certainly Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane dance company was a community… That community thing changed radically when all of the sudden it was, how do we save ourselves?”

As the film progresses, the more I think about these dancers tasked with performing D-Man in the Waters and what a tall order that is. It surprises me how captivating the students are, both their willingness to learn the dance and their struggles to find motivations that give the dance meaning. Near the end of the film, when the dancers are in a final rehearsal, LeBlanc asks the question again, with more urgency bordering on panic. What do they have to bring to this? What can they do right now onstage? When the dancers find a contemporary issue to push against, they become joyous to watch. They soften into each other’s bodies, a head leans into another’s shoulder, and they push through the movement as if they could break through the stasis. At one point LeBlanc says to one of her dancers, “no matter what, keep going.” In a work born out of sorrow, there is also joy, beauty, laughter and power, and a resilience that through the unrelenting work of the movement, we can learn how to keep going.

Can You Bring It: Bill T. Jones and D-Man in the Waters, a film by Rosalynde LeBlanc and Tom Hurwitz streaming through Light Box Film Center at University of the Arts, July 16-25.

By Kristen Shahverdian

July 20, 2021