What has 4 legs in the morning, 2 legs at noon, and 3 legs in the evening? In the culmination of their residency at Baryshnikov Arts Center in New York City, Baye & Asa mobilize this question––the so-called Riddle of the Sphinx––through three different generations of dancers who come together to trace the course of a human lifespan.

The first section of 4 | 2 | 3, “4,” features three tween age dancers––Leora Champagne, Kristen Lieng, and Sasha Lecoq––wearing identical gray pants and button-down shirts. The set behind them resembles a concrete building. A tube reminiscent of a playground tunnel zapped of its color juts in from stage left. The music, composed by MIZU, grinds out bass-heavy white noise as the dancers crawl around one another and switch between various positions on the floor. They perform traveling footwork in unison, clapping and stomping in a world somewhere between teamwork and bullying.

It’s rare to see this kind of engagement in the realm of concert dance, even though children are often artfully included in other artistic mediums like film. The young dancers achieve a cohesive aesthetic with their relaxed feet, sweeping arms, and swirling spatial patterns. The section ends with a lighting shift and musical build as two dancers stride upstage toward the third. They seem domineering, but the lights go out before we can get in on the action.

Section “2,” the longest part of the dance, features Frances Lorraine Samson, Kyle Martin, Lily Gelfand, Megan Siepka, Mikaela Brandon, and Nick Daley in matching black long sleeves and pants. They move seamlessly into and out of unison, rotating partners and formations. The transitions are so embedded into the choreography that they are nearly invisible; when one partnership ends, another is already beginning. Though athletic and dynamic, the choreography exhibits significant restraint. The music, seemingly already at its maximum intensity, somehow continues to build.

One moment, the dancers are silhouetted by a flickering LED light above the set door, and the next, they are backing away from the window, voidlike in its utter darkness. When they hold hands Ring-Around-the-Rosie style, they look each other in the eye and smile; sometimes their smiles feel natural, and at other times, they seem forced. There’s something mathematical about how they move in relation to one another and the music, but I can’t quite figure it out: what are the stakes? When the door of the structure finally slides open, someone goes through it without much fuss. Even when the dancers climb over and under the tube, I can’t help but think that the set seems insignificant and even unnecessary.

The piece’s most visually memorable moment comes when one of the dancers stands on top of the tube performing a trendy gesture phrase with lots of energy through the fingers and occasional grabs of the head; eventually, the light illuminates only his face, making him resemble the bust of a statue. While the rest of the work revs and bleeds into itself, this moment is striking, distinct, and punctuated. In another standout moment, the group marches in a clump, flashing vehement gestures and wild faces as they travel around the stage. Some of their repeated handshapes seem to symbolize weapons, and the relationships between the dancers grow more confrontational. The section ends similarly to the previous one, with ominous string music overwhelming the space.

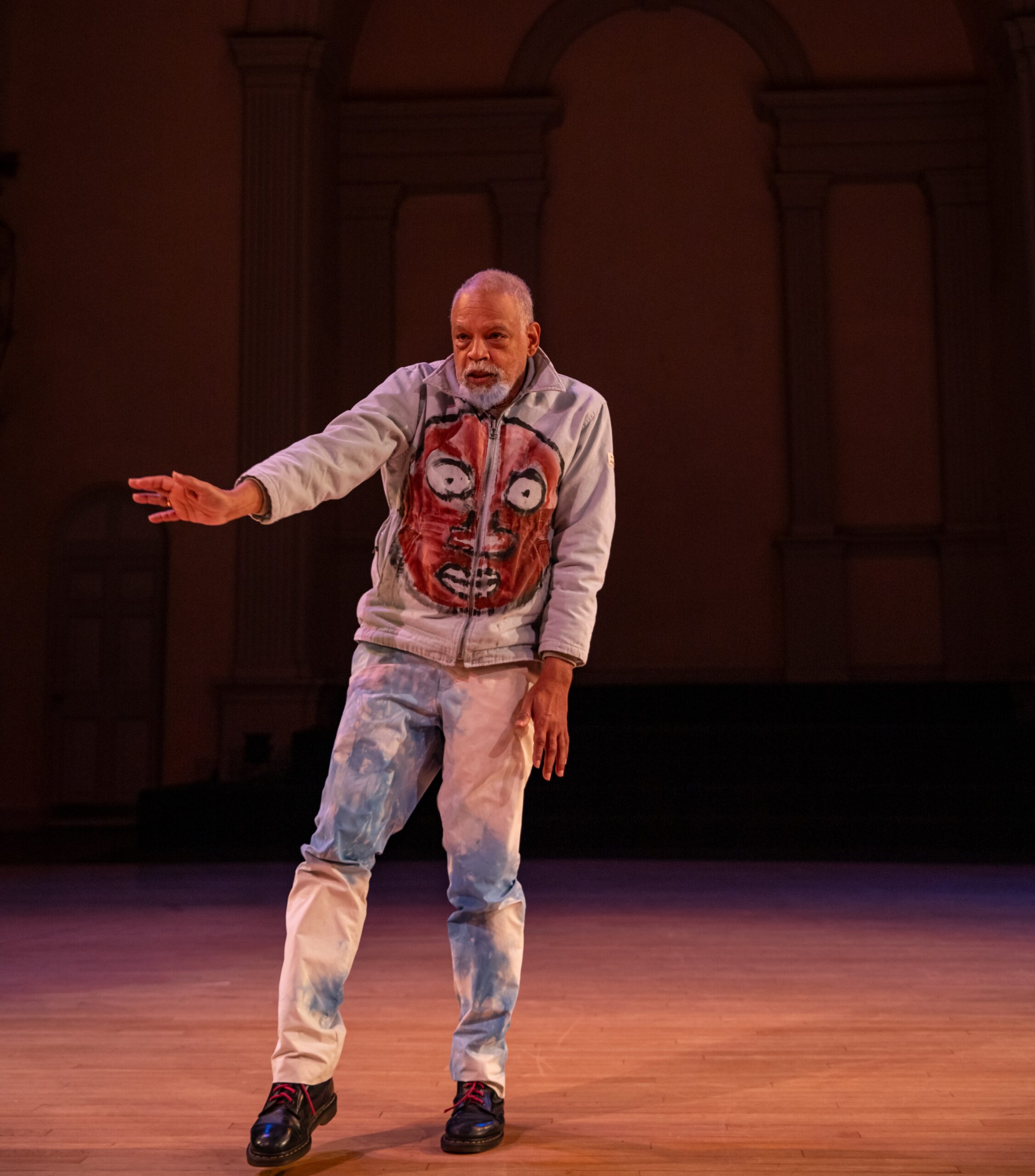

Section “3,” the shortest part of the piece, features Janet Charleston, an older dancer who performs a captivating solo with variable textures, rhythms, and dynamics. She tips off balance regularly with a soft neck and swinging arms. When she takes down her very long silver hair, the tunnel illuminates from within, sending fog across the theater. Is this a different kind of void from the dark window before? The group joins her on stage, walking toward the light as the music fades.

Contrary to many of their recent productions like Suck It Up and The One to Stay With, Baye & Asa’s 4 | 2 | 3 doesn’t use much everyday imagery and relies more on abstraction. Though the program claims that the work is a reflection on humanity’s industrial history and a grappling with our collective search for blame, I did not find the piece particularly legible as such. Instead, it felt almost purely aesthetic––an undeniably satisfying aesthetic, but lacking the punch and memorableness of many of Baye & Asa’s other works.