The Rear-View Mirror: Hindsight from a Dance Scholar

by Megan Mizanty

Susan Manning’s name hasn’t changed, but the name of her life’s work has.

A founder of critical dance studies, Manning started out “[D]eclaring it as ‘dance history’....now I call it ‘dance studies,’ a shift in appellation [circa 1990] as distinctions blurred between archival, ethnographic, and theoretical methods for dance research.” This steady evolution is chronicled in Dancing on the Fault Lines of History: Selected Essays. Although this 346-page single volume was published in January 2025, the non-chronological chapters are gathered from 1986 to present day.

This decades-spanning text is a rich and comprehensive accumulation of foci and meaning over time, interlaced with semi-autobiographical annotations preceding each chapter. I found these passages the most fascinating, as they offer a vulnerable retrospective on an esteemed scholar’s life’s work (i.e. What has changed about Manning’s understanding of different seminal pieces in the modern dance canon? When and why did Manning shift her focus? How would she have approached her analysis differently if viewing dances, for the first time, in another decade?). Dancing on the Fault Lines is a distinct and enduring invitation into the writing–and re-writing–of modern dance history.

Manning, a Bergen Evans Professor in the Humanities at Northwestern University, divides her book into three major sections: gender and sexuality, whiteness and Blackness, and nationality and globalization. While reading Dancing on the Fault Lines, I imagined these words as different lenses viewed on/over dances and choreographers, influencing Manning’s response and analysis to artists such as Reggie Wilson, Vaslav Nijinsky, Katherine Dunham, Isadora Duncan, Pina Bausch, Nelisiwe Xaba, Mary Wigman, and more. What factors–such as queerness, strategic assimilation, political statements and subversions–were initially blurry? When switching the lens, what components of a moving body come into focus? Manning is, above all, a scholar. Her writing shines in intellect, and specific passages had to be read multiple times to land and resonate. For non-academics, sections of the text may be daunting to navigate. I questioned the audience of Fault Lines. Was it compiled for the next generation of critical dance studies scholars? For undergraduates stepping into dance research for the first time? For graduate scholars desiring to continue the expanding field of transnational dance studies? Or, for women planning and striving for a sustained career in academia?

In the 1970s, Manning was all of these things. The first of the first. Throughout the text, I noted many of the moments she was the only woman in a room: the first tenure-track female professor in her department, the first cohort of students in the first women’s studies class at Harvard. She writes, “As an aspiring dance historian, I was essentially self-taught, reading the existing literature in the field.”

Although the text does not examine Manning’s own dance practice or choreographic body of work, she reflects on her encounters with the works of other prominent choreographers throughout history as an avid watcher of movement.

The final (and oldest) chapter, entitled “An American Perspective on Tanztheater” begins with Manning’s present annotation/reflection: “In fall 1985, I was far from alone in my fascination with [Pina Bausch’s] work…it was a relentless focus on gendered roles…I interpreted the images of gender as commentary on the confusion between victims and victimizers in the German memory of the Nazi period…not until 2009 did my interpretation of [Bausch’s] significance move beyond national borders and highlight the global influence of her company’s tours.”

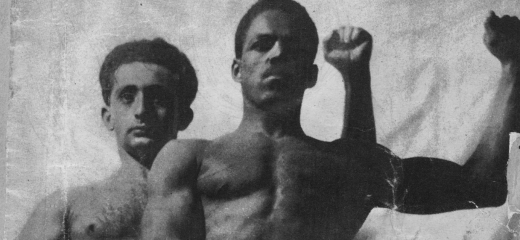

It’s these past/present annotations that weave this text together, showing how, when, and why the understanding of a dance could change as time passes. How will we view Bill T. Jones’ Last Supper at Uncle Tom’s Cabin/The Promised Land (1990) on its fiftieth anniversary in 2040? How will José Limón’s The Traitor (1954) be appreciated differently from a queer or theological perspective in the latter 21st century? Manning shares that “[The Traitor], an all-male work, premiered at the American Dance Festival. Although photographs widely published at the time suggest a subtext of same-sex desire in the action, not one published review even hinted at such a reading…the power of a work like The Traitor enacted a tension between what was seen and what was not seen.”

Manning gives the reader an invitation: what do we see in dance in 2025? Globalization, sex, race, protest, AI influences, archetypal roles? What are we missing? She also gives us permission to edit: as critical dance studies scholars, any analysis is steeped in our respective times–the temper of an age, the values, the sociopolitical movements, the technological advancement, the possibilities to see “otherness” via travel, institutional support, and opportunity. If the gaze widens and expands globally, so do our experiences of viewing moving bodies. Who will we discuss decades from now, and how will our lens switch?

Dancing on the Fault Lines, Susan Manning, University of Michigan Press, 2025

Homepage Image Description: In a soft, blurry black and white photo, dancer Mary Wigman performs in Idolatry (Götzendienst), part of the solo cycle from Ecstatic Dances as revised for her first solo tour in 1919. She wears opaque black tights, shoeless, and a thick fringed black dress that covers her entire torso. It’s difficult to tell, but the shadowy form looks to be throwing her head back. Photograph Courtesy of the Mary Wigman Archive, Academy of Arts, Berlin.

Article Page Image Description: Hy Boris and Add Bates, two lean and muscular male dancers, stand shirtless and flex their biceps in a pose reminiscent of Edith Segal’s Black and White. Their faces are powerful and commanding.

By Megan Mizanty

August 25, 2025