Photo: Ellen Chenoweth

There Can Be an Ease

by Ellen Chenoweth

“I get obsessed with materials,” the long and lean Wilson explained to his class. At the moment, the material he’s obsessed with is mouse traps, the kind that snap onto the mouse when triggered.

How hundreds of mousetraps ended up in a dance class is related to the dialogue between performance art and performing arts currently underway, and to the curriculum changes taking place at the School of Dance at the University of the Arts under the direction of Donna Faye Burchfield. Burchfield believes in pushing against disciplinary boundaries, and puts forward an expansive vision of the dance field: “Dance has emerged as a contemporary practice within a much broader field of art and art making. It is essential that our students are exposed to contemporary ideas and practices through comparative critical thinking.”

I’ve admired Wilson’s performance-art work for several years and visited his class at UArts on November 24 to see how his practices and those of undergraduate dance majors might influence each other.

Wilmer Wilson IV is an M.F.A. student in Fine Arts at the University of Pennsylvania, recently relocated from Washington, D.C. While coming from a visual art background, his practice is often centered around the body, as in his work Henry “Box” Brown: FOREVER (2012), in which he covered himself with thousands of stamps and attempted to mail himself from several post offices, in a pointed commentary on slavery and freedom, both in the time of the original Henry “Box” Brown and today. Brown, a slave in Richmond, Virginia, successfully mailed himself in a crate to abolitionists in Philadelphia in 1849, thereby becoming a free man.

Michael Sheridan, Assistant Professor at University of the Arts, acted as an artistic advisor and assistant in the class, titled Pedagogies of Performance in Dance (PPOD, colloquially referred to as a pod) for fall 2014. He described coming across Wilson’s work online and getting excited about both the ideas and their execution. “I rearranged my whole schedule so I could be here for this class,” explained the former Pennsylvania Ballet dancer.

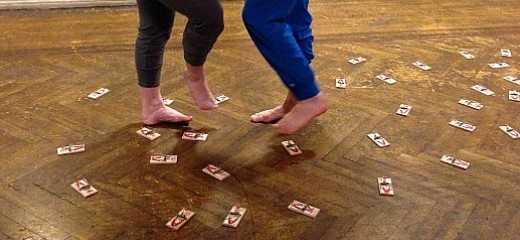

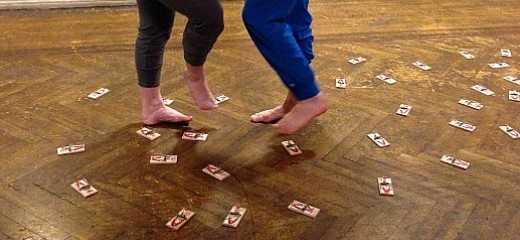

Back in the classroom, Wilson and the students have arranged mouse traps along a stretch of floor, and the assignment of the day is to cross the mouse-trapped floor in bare feet, holding a videocamera, and filming their feet as they navigate the crossing. The 15 undergraduate dancers are stoic. They’re stepping far outside of the comfort zone of a traditional technique class, but no one breathes a word of complaint. After the first dancer crosses the floor, she notes softly, “it’s really scary.”

The students do the exercise in various permutations, sometimes alone with the video camera, sometimes two at a time with one filming, and sometimes with a train of students, all at various speeds. The versions with two students are the most compelling to me as a live viewer—watching two people negotiate this intimate and emotional physical experience.

There is a sense of freshness from both instructor and students—that what’s taken for granted by one could be new and interesting to the other. “What’s a crescent roll?” Wilson asks at one point, after the movement comes up in conversation during class. A student jumps to the ground to demonstrate, his head and his feet curving together, making the body taut until a flip is inevitable. Wilson is intrigued and films the movement for later reference. (A student sensing his interest whispers, “hashtag inspired.”)

The process for joining the class was as unconventional as its content. Visiting artists Eiko Otake, Esther Baker-Tarpaga and Wilson all held auditions during the same session. Wilson’s portion of the event involved prospective participants in the class submerging their hands in water from the Atlantic Ocean for five minutes. Before the submersion, Wilson told a story of a slave in Massachusetts who was offered his freedom if the tide receded enough between the shore and a certain patch of land. Wilson told the auditioning students, “If you found this interesting, you might be right for this pod.”

Junior Matt Emig described his biggest takeaway from the class as learning from Wilson’s style of making work. “I’m impressed with his agency; he can just do things for himself. In dance we think there are all these prerequisites to making work, but there can actually be an ease, we can do it whenever we want.” As the dance field becomes increasingly interdisciplinary, training that engenders new ways of thinking and promotes perspectives that are based in other kinds of studios are becoming increasingly important.

Wilson praises the class as causing a “paradigm shift” in his art making. “I got to rigorously think through the possibilities of using multiple bodies. I became hyper-aware of how much overlap there is between dance history and performance art history. I will be looking to collapse those separations and have these complementary bodies of knowledge inform my work from here on.”

(Some of the outcomes of the mousetrap experiments, as well as another piece created in Wilson’s class can be viewed

here.)

By Ellen Chenoweth

December 19, 2014