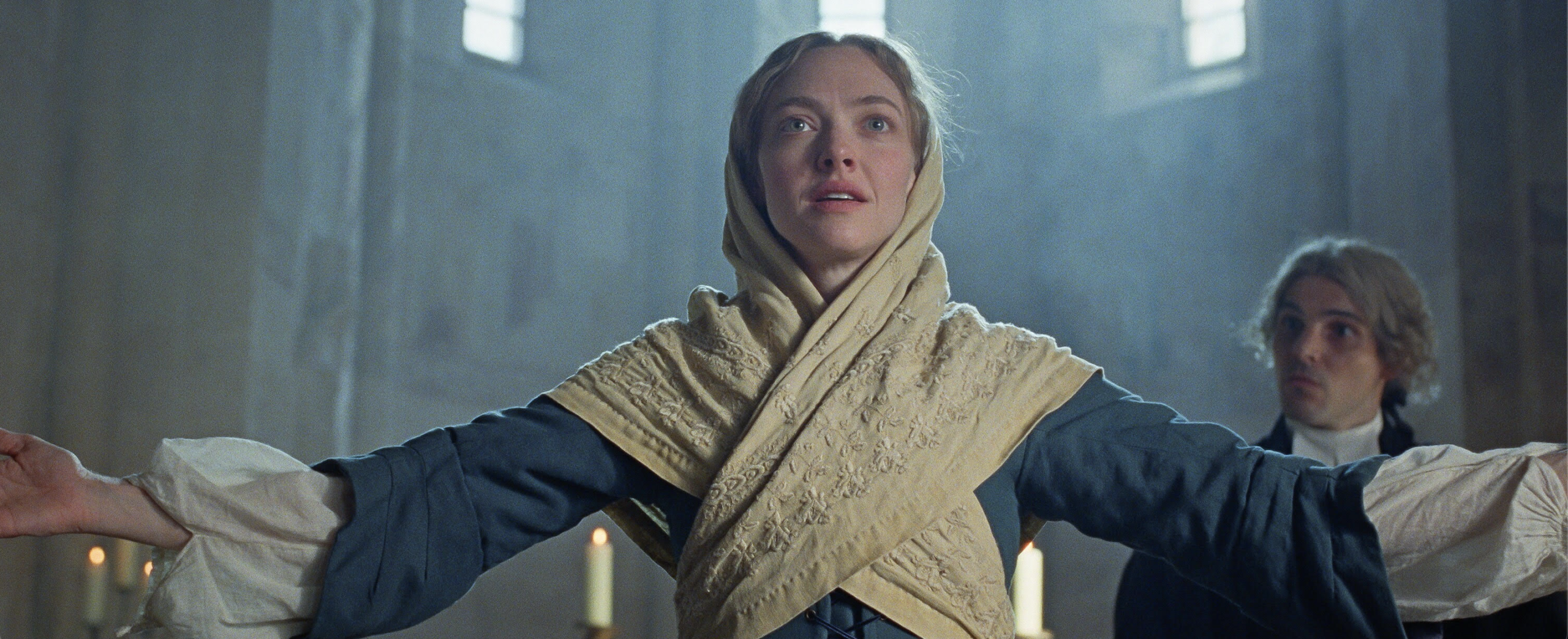

There are ten thousand things to attend to in a dance program. Among them: movement, phrasing, meaning, line, execution, production values, lighting, sound, costumes. But sometimes a piece tells you which part you should consider first and foremost. Sometimes there is a more insistent thread. In the halves of Unveiled, the ethos of each of two choreographers was prominent and compelling. Their differing approaches worked in contrast—a contrast that enhanced the evening.

In many literary criticism circles, it is considered an error (of logic, and irrelevant besides) to try to ascertain the intention of the artist through the lens of the work. But I have always been suspicious of any rules about how to interact with art—I was the child who maneuvered her face perilously close to Van Gogh’s brush strokes, making security guards nervous. So when I watched Jessica Warchal-King’s (in)visible veins, I first noticed dancer KC Chun-Manning’s open-bodied gathering gesture as she wound the space around her like so much yarn. Watching the specificity of her speaking palm, her wide stance, her circling pelvis, two words came to mind about this choreographic project: taste and invitation. And indeed, throughout the piece, the generosity of the movement and the sometimes careful and more often care-taking focus of the five dancers moved both in- and outwards.

When Belle Alvarez and Jodi Obeid shared the stage, their interaction with one another took conversational turns, the repetition of opening palms at their hips a gently insistent motif. Warchal-King did not limit significant gesture to the hands: a repeated inversion with a foot reaching toward the audience served also as a kind of request. The dancers imbued many of their phrases with palpable subtext. I might not know the language being spoken, but I felt the communicative efforts between them and towards the audience, and I read intention in their faces.

At the Performance Garage, lighting and proximity make it possible to see the dancers’ eyes meet, and soften. These women in flowing white proffered an openness, an expansive yet grounded movement vocabulary replete with foot stomps reminiscent of European folkdance, culminating in a semi-circular unison passage that created a community of the stage. The title (in)visible veins evoked for me the constant pulse of Warchal-King’s phrases and the guitar music underlying them, and of the lines of connection between humans (perhaps especially between women) who choose to come together to share meaning.

Brandi Ou’s work Not All Who Wander Are Lost did not invite: it demanded witness. Using a mix of live percussion (provided by onstage musician Brett Cohen), taped music, and recorded text, Ou’s work began with struggle and ended with vulnerability. If the first half of the evening made a village of the stage, the second half showed what a collective looks like in conflict, even torn asunder. A duet between Ou and Lauren Williams stood out for its power and dynamism. Both dancers are unafraid to push to the ends of their movement in the service of dramatic action, but they also know when to pull back from the edge to create suspense, a sense of reserve, a quiet tension. I found myself drawn to moments in the work when an explosive fan-kick ended in softness, when a trio relinquished apparent control to be puppeted by the music. Ou’s choreographic rhythms are complex and nuanced, and the sections when Cohen accompanied the dancers highlighted these strengths.

Not all Who Wander ends with a series of disrobing solos to autobiographical texts. These moments of exposure, unfortunately, have become a trope that has lost a great deal of its power—near-nakedness no longer shocks, and onstage memoir work is less charged than it was before Bill T. Jones (and others) pushed this tactic into the mainstream.

It was lovely, however, to see Cohen put down his music to participate in this moment. His untrained (in dance) physicality helped to reclaim some of the initial risk of this act, as did Ou’s final textual statement, embracing her Christianity as essential to her selfhood. I’m not certain quite how this final admission fit with the piece in its entirety, but I do know that it left me wondering just what makes us feel naked—if it is no longer the fact of nakedness itself. As I reflected on Ou’s work and its themes of dissatisfaction, struggle, and the profound longing for connection, that question proved a useful one.

Unveiled, Jessica Warchal-King and Brandi Ou, Performance Garage, April 18.