Sometimes you do not control the circumstances surrounding your entrance into a theater.

Sometimes you are not in control of what wells up inside of you in response to art.

Sometimes, maybe that’s what art is.

*

My sister Mary’s mother died Friday.

Mary came to live with me two months after I turned 13 and one month before she turned 14. When she came to live with me I called her cousin.

None of this has anything to do with the show I’m about to see.

*

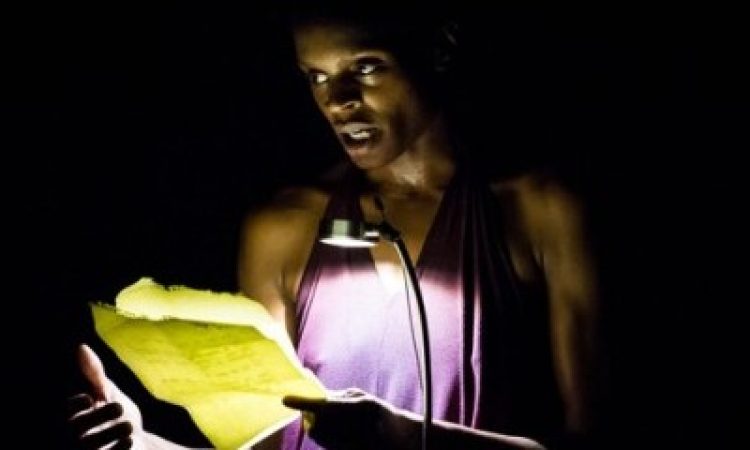

In Bronx Gothic, Okwui Okpokwasili tells the story of two girls coming of age in hate-love. She tells this story through her body, through reading their loose-leaf letters, through threading together snatches of song. The girls’ bestfriendship demands and flaunts its honesty, the kind that can be cruel but never heartless. This intersection of oppositional energies is the excruciation of adolescence.

One of the girls recounts a grown man telling her her black is so ugly she’s almost beautiful.

*

When I met Okwui, we were 18, and she was stunning. I was in my dorm room at Yale with my parents (who’d done this same song and dance at American University with my sister Mary a year earlier) and my roommate walked in—a six-foot-tall drink of water, dark-skinned, a smile that lit up the whole hallway. She was self-composed with a deep velvet voice meant for the stage or for a different era of radio, and my mom and dad immediately adored her and her family. With our parents at ease and chatting, Okwui and I decided on bunks. She took the top and me, the bottom.

*

My sister Mary and I shared a bedroom for three years. Sometimes, after the lights went out we’d talk. My memory of these late night sessions was that—as the slightly younger and less mature—I was always trying to glean something from her: the undisclosed details of her difficult past, some recipe of how to be with boys (it seemed to me she knew all the secrets), what guy she was crushing on… flirting with… dreaming of. In short, I wanted pieces of my new sister. I felt entitled to them.

Mary wrote in a diary with a lock, and I was not entitled.

She’d been dropped unwittingly into our large family, her younger brother and sister (whom she’d been parenting before her time) living a few miles away now in another relative’s house. Her young mother Moira had given her children to her cousin and her sister to finish raising. These are some of the complexities of family love.

*

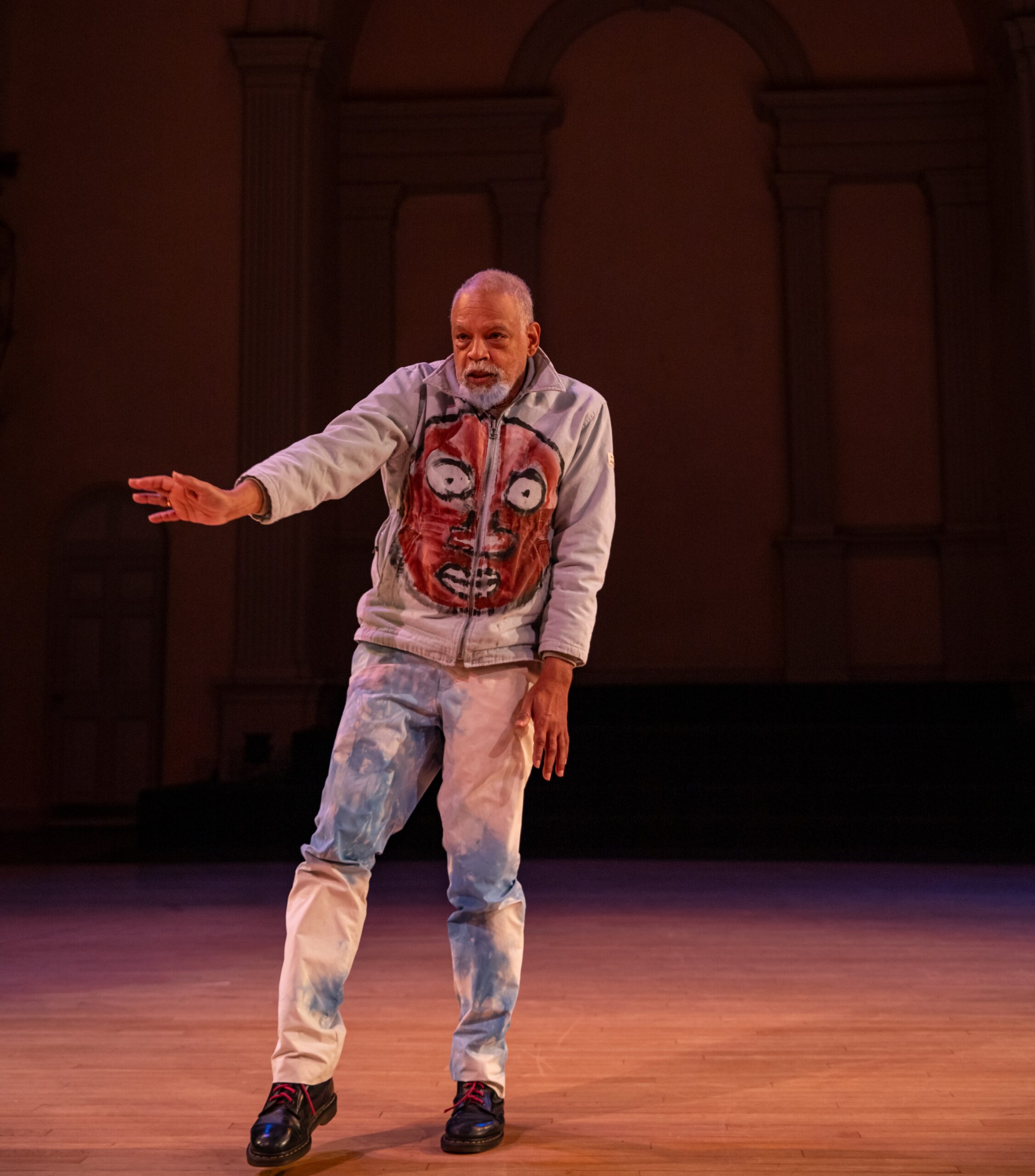

As the audience walks into New York Live Arts (where Okwui is performing this sold out encore performance after being named NYLA’s Resident Commissioned Artist in July), they see her in a knee-length halter dress, trembling, dancing, muttering, and posturing into a corner draped in white fabric. She doesn’t stop moving and by the time she turns and makes her way towards the microphone thirty minutes later, still vibrating like an engine, the ropy muscles of her back, legs, and arms are drenched with sweat. Her embodiment of this story will be won through hard physical labor. The girls’ voices she engages (one tremulous and childish, the other not), the fragmentary songs, the gestures she uses to identify side characters (mother and mother’s predatory boyfriend and Ricardo, one of the girl’s firsts): every bit of fractured narrative is starkly defined in her body. The pieces don’t come easily, but like shards of a broken mirror—glued back together—they reflect a sharp and bloody time. The time when a girl is becoming a woman… sometimes without full understanding, sometimes against her will.

*

When we left home for college, my sister Mary and I were not what anyone would call friends.

*

I emailed Okwui a few days before I came to New York. I haven’t seen her in two decades. We were not close in college, though she always welcomed me into her circles. A force of nature, a dancer and actress and singer, she was cast contra-gender as Judas in the Yale Mainstage production of Jesus Christ Superstar senior year, defying easy description then as now, mildly androgynous and magnanimous and utterly magnetic. Three years after our first fall together I was still known to some as Okwui’s roommate—a tighter bud, smaller in ways that had nothing to do with our relative heights. In our email exchange she mentioned that at that time she’d felt riddled with holes. I wrote back, “and who was not?”

*

Mary’s mother Moira was 15 when she had Mary and 60 when she died. I was in Chelsea, heading to the show, when my mom called. She told me Moira had passed. After a long up-and-down illness, her last few hours were peaceful, and her three children were at her side.

Nearly a year ago, my sister Mary brought her dying mother into her home to ease the coming transition.

Mary’s own children—my niece and nephew—they have a remarkable mother.

*

Okwui’s show is about brown girls in the Bronx in the 1980s. The specifics—the taste of Newport loosies, the smell of Vaseline Intensive Care, ripped-out note pages passed in class, fire-drenched dreams of Orchard Beach—conjure a very particular time and place. But the girls themselves and the way they alternately bloom against one other and are blocked, the way they hate-love and share-shame and intertwine and thrash inside each other’s narratives: this is a sister story. A story of sisters made not born. Girls so hungry they suck on each other’s dreams as if they were the last of the grape Now & Laters at the close of a long school day.

Bronx Gothic ends with two girls so close they sometimes seem one, and so far apart we doubt they ever really knew one another.

Except—of course they did.

*

My sister Mary got pregnant with her first child six months before I did. She decided (she’s the decider) that our sons would grow up to be close. Then she made sure it happened. During the same period, we too became friends. I am so grateful. My nephew lived for a month this summer (his sixteenth) at my house while he did lab research at Drexel. He and my son talked every night, played videos, did whatever teenage boys do when their parents aren’t bearing down on them. Not too long from now, they will be leaving home for their respective colleges.

*

There are people against whom you measure yourself as a person. People who live side-by-side with you during the time when you are becoming yourself, for better or for ill. They serve as both your mirror and your negative image. You fill in the gaps they leave. Once they are out of the room you shadowbox their phantom or sucker slap their imagined face or you try on their bra. It doesn’t fit. You are the shy one or the short one or the darker one or the ugly one. And they are the center.

Sometimes, later, you are lucky enough to learn that—during that same time—they were piecing themselves together through the same incomplete processes, using the same Elmer’s glue, the same glitter, its tiny broken mirrors.

We are all we have.

*

Okwui Okpokwasili tells two stories with one body. That’s how storytelling works. It’s also how anyone comes to know anyone else, by learning their story from the inside out. We rewrite the other’s text on our own inner walls until we are—until we have no choice but to be—each other’s.

Bronx Gothic finds its grace in the hardest moments of girldeath, in its reversals and betrayals and gaps, the dark places in each other we never do get to read.

Yet the work never lets go of this idea—the fact of our holes does not negate nor erase what we were capable of sharing… no matter how riddled.

*

Broken glass, glinting off asphalt, catching starlight.

Bronx Gothic, Okwui Okpokwasili, New York Live Arts, October 21-24, www.newyorklivearts.org