Clicking through a folder of images, many of them brightly colored and carefully composed, I am suddenly absorbed by a picture that is more difficult to decipher. A figure cloaked in shadow-mottled fabric seems to hover in the center of the frame. Two curved arms create a slightly distorted X with what must be the figure’s knees, the legs presumably folded up under the cloth. The edge of a foot signals the presence of a body behind the fabric, yet I can’t make out where, precisely, the head has gone. Behind is a flat black expanse.

I stumbled upon this image while exploring The Jack Mitchell Photography of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater Collection. The archive includes over 10,000 photographs and is made up of an assortment of portraits, posed dance images, and rehearsal and performance documentation. On Dec. 1—the 30th anniversary of Alvin Ailey’s death and also World AIDS Day—the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture made the entire collection available for the public to explore online.

Produced by Jack Mitchell, a photographer known for his portraits of American artists, the images in this collection chart the development of Alvin Ailey and his company over the course of more than three decades.

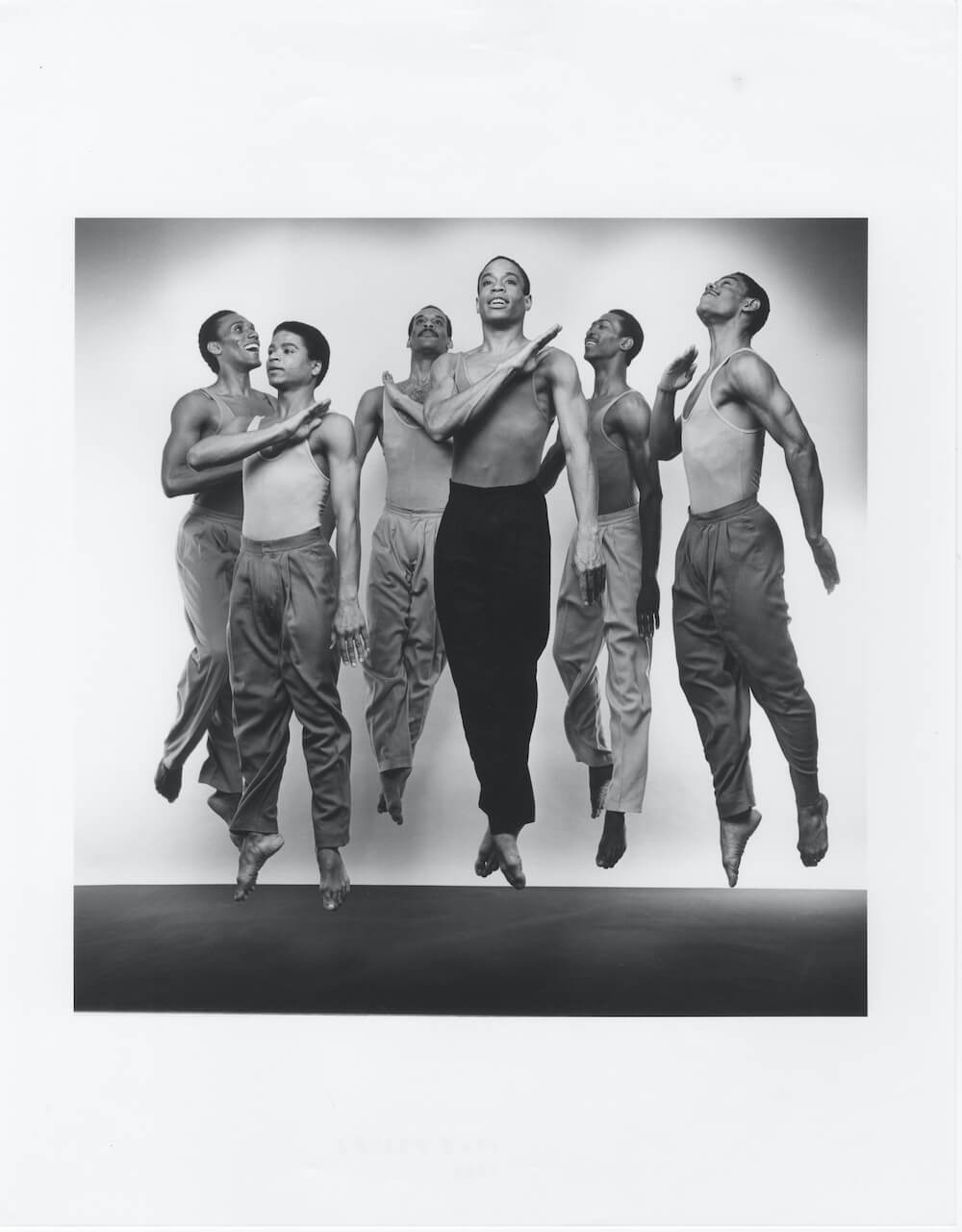

Rodney Nugent, Ronald Brown, Kevin Brown, Keith McDaniel, Danny Clark, and Gregory Stewart in “Fever Swamp,” 1983. Photography by Jack Mitchell, © Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation, Inc. and Smithsonian Institution, All rights reserved.

Spending time with an archive of this breadth offers many unexpected discoveries. The image I described above depicts Ailey in a 1961 performance of “Hermit Songs,” a work previously unfamiliar to me. Although Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater continues to perform many of the works documented in the collection, behind-the-scenes photographs add nuance to familiar dances, and the digital accessibility of the archive allows those living outside of the company’s usual touring circuit to see images of the company’s most iconic works.

The archive certainly reaffirms and deepens the legacy of Ailey and his company. But to fully appreciate the significance of this archive’s unveiling, it is worth remembering the position that a collection focusing on a gay Black artist holds within the history of photography and its archives.

Given that racism fundamentally affects the way people see the world, it is no surprise that racial bias is woven into the medium of photography. Photographs have long promoted exoticization and racial fetishism, and white skin was used as the norm when developing color film technology, a history which continues to shape photography today.

The history of photographic archives is also steeped in racism. As Allan Sekula lays out in his essay, “The Body and the Archive,” the first official photographic archives were developed within the police system in an attempt to identify criminal “types.” Often pairing photographs with written physiognomic and phrenological analysis, many of the creators of these archives espoused explicitly eugenicist beliefs. In opposition to the criminal and racial “others” they identified, these early archives generated fantasies of the “average man.” Similarly, more contemporary archives reinforce normative histories through the exclusion of marginalized voices.

The Mitchell/Ailey collection is not free of these histories; Mitchell was white, and there are surely ways in which ingrained biases worked their way into his images. Yet, both the content of the images and the nature of the online database itself manages to work against some of these racist legacies.

Judith Jamison with Company performing “Revelations,” 1992. Photography by Jack Mitchell, © Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation, Inc. and Smithsonian Institution, All rights reserved.

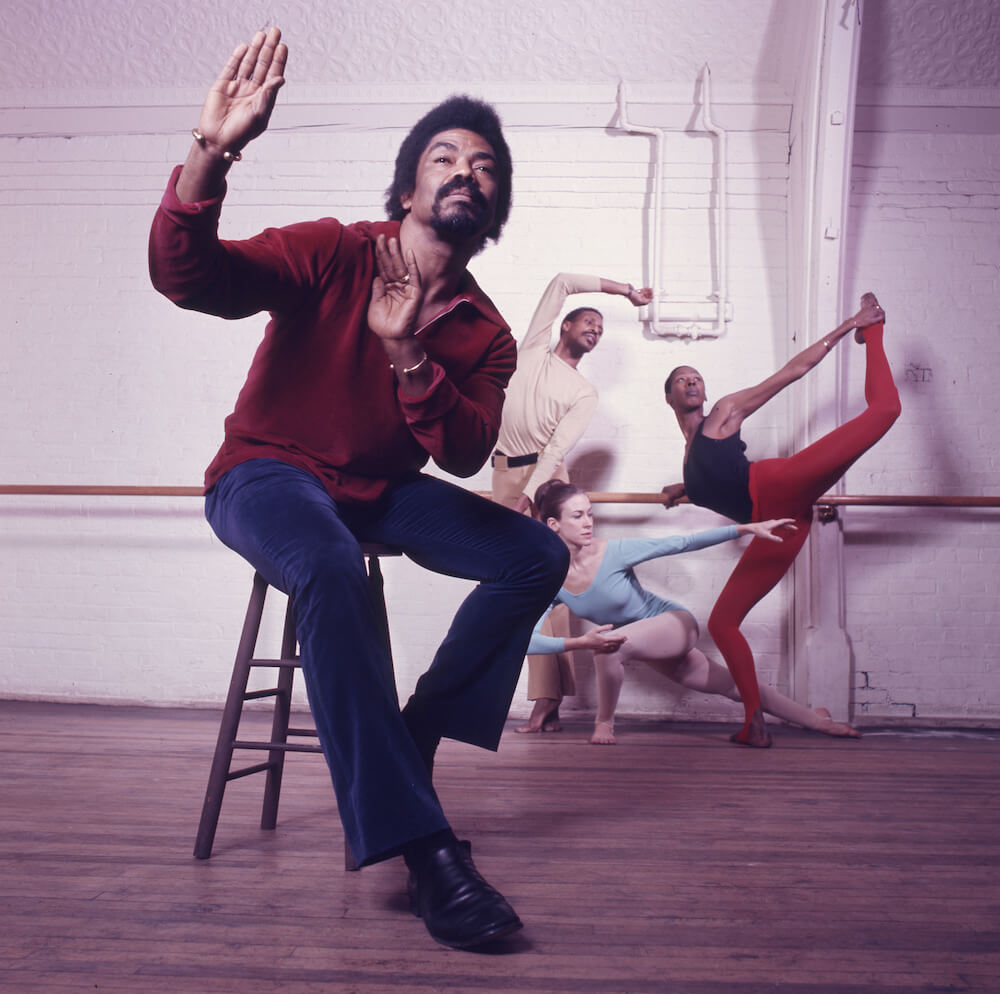

It is illuminating, for instance, to look at one of Mitchell’s many studio portraits of Ailey. Sitting on a stool, Ailey looks slightly up and off into the distance. He rests one hand on his knee while holding a composition notebook in the other. The camera is positioned at a low angle so that the viewer looks up at Ailey. Each element of this image utilizes art-historical tropes to underscore Ailey’s artistic and personal power: the three-quarter angle of Ailey’s torso and his upwards gaze adhere to norms of heroic portraiture; the notebook in his hand follows a tradition in which great artists are depicted holding the tools of their craft (as in this portrait of the architect Palladio). In opposition to archives which conspicuously excise or diminish the work of Black artists, photographs such as this one reinforce Ailey’s place within an artistic canon.

Portrait of Alvin Ailey with Judith Jamison, Linda Kent, and Dudley Williams in dance studio, 1973. Photography by Jack Mitchell, © Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation, Inc. and Smithsonian Institution, All rights reserved.

What’s more, unlike historical archives that attempted to make individual photographic subjects representative of larger “types,” this archive appreciates individual specificity. Photographs are always accompanied by the names of any dancers that were pictured, and the sheer volume of the collection troubles any attempt to make a fixed generalization about Ailey and his work.

The public release of the Mitchell/Ailey collection would have been meaningful simply for the light it shines on an icon of modern dance, but it gains even greater resonance when seen in counterpoint to this flawed history. As a multilayered portrait of a company as well as an example of an archive moving towards decolonization, the collection is sure to fuel artistic discoveries and dance scholarship for years to come.

*Top image: Judith Jamison in “Revelations,” 1967

thINKingDANCE has covered Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater a number of times, both in the past and more recently.

The Jack Mitchell Photography of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater Collection, Smithsonian’s Online Virtual Archives, published 2019.