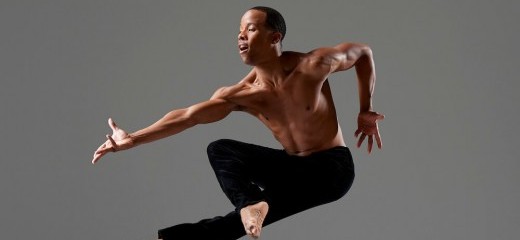

An Interview with Iquail Shaheed Part 2: The Future of the Dance Institution

by Mira Treatman

Ahead of Dance Iquail’s Art Thrives from Black Lives: An Artistic Rally, I interviewed community leader, executive artistic director, dancer, professor, and rally organizer Iquail Shaheed. Part 2 The Future of the Dance Institution is a series of edited excerpts from our conversation on Zoom. Part 1: Black Love and Tenderness on Stage can be found here .

Attend this peaceful artistic rally on June 27 from 10am to 3pm outside of the Community Education Center.

Mira Treatman: I hear you describing threats to your work and life coming from many directions. Other than the obvious, what are the biggest challenges?

Iquail Shaheed: The obvious for me is the system of supremacy that doesn’t allow our work be appreciated or supported financially. As a result, organizations with whom we endeavor to partner with to deliver services to youth and communities find themselves needing to prioritize other aspects, like food and healthcare, that renders arts organizations not able to deliver our services. Funders don’t see how working with youth is gun violence prevention and disrupting the school-to-prison pipeline. They don’t see that our work creates job readiness and a workforce in the arts. Those are significant threats to who we are, to doing this work that goes under reported. The socialization is to think that art is about consumption that must be presented on stage for people to watch in a theatre and consume. They miss that we have an arts program in Mantua where we don’t have gyms anymore. Our work combats obesity and diabetes and asthma. We need people to understand that it’s much more than movement around a stage.

MT: That sounds like what white supremacy and its related plagues value, right, is that more or less what you’re saying?

IS: Yes absolutely, we can name white supremacy. We can name that. We can name the white privilege that allows them to frame the boxes. If you don’t fit into the boxes because your life never fit into a box, then you’re penalized because you don’t fit into their boxes. We’re always caught trying to push back on those things because you need to get inside the box to blow the box up. I also don’t want to be inside the box because it alienates and ostracizes what I’m here to do, which is to liberate people from boxes, so that people can just live. Isn’t that worthy of being supported in its own right?

MT: Yes! So these boxes, these are dance institutions, presenters, funders…?

IS: Yes, it runs the gamut. Even service organizations. If it is not ballet or modern then is it really dance? That’s a box. Are drill teams not dance? Are you not using your bodies to music in space with directions? Isn’t that dance? Or Double Dutch! The way they move their bodies with an apparatus. Is that not dance?

So we live at this intersection of art and social justice, we keep getting asked “is it social justice or is it art?” I’m like, “Why can’t you see that they’re both and the same?” That’s another box. That’s where we lose funding opportunities because if it’s art and an arts funder, it’s about a product on stage, and it’s not about the way we work with people, the way that we use our art to build stories and capture data and change lives. If we happen to create a work from it, then we happen to create a work from what we do, but that is not the goal. So this often cancels us out from arts funders that are about a product. With the social justice funders, they want quantitative data. In order to fit the box that you need to fit in. How many kids will remove guns from the street if we fund you? That’s what they’re interested in. How many kids will go to college from your program being funded by us? They miss the fact that social justice and social change is also about how we connect with those individuals, how we change their lives. Qualitatively. We need them to understand this is just as important as quantitative data.

MT: If you could design a grant report, what would it look like in a perfect world?

IS: I gave a similar comment at the Dance/USA conference a couple days ago. We should do a cultural audit and create the framework for it. Make it just as rigorous and rigid as a financial audit in order for us to get grant funds. There’s a big foundation in Philly we haven’t ever qualified for because you need three years of an audit with less than 5% of a deficit in any of those years, and you have to have consecutive years of audits, so if you miss a year then you don’t qualify. There are certain rubrics about cost analysis vs. income analysis in order to be a successful audit for them, in order to be eligible to apply. We need the same thing in terms of culture. It needs to be just as rigid. The metrics need to illustrate how much of your diversity is directly tied to bringing in money and how much of your diversity and cultural awareness is actually about people. That ratio is the determinant of your deficit or your surplus. That’s the framework we’ll be able to right this supremacist culture. Those big institutions like dance companies will have to start to invest in the people without trying to invest for a return financially, but will invest for a return of cultural change. How are people reporting issues of culture? How are they having resources from the organization, spaces, choreographers, costuming, staff, board? How are the minutes of the meeting documenting their experiences and also actions that are measurable? This is the cultural audit that I’m pushing the field to do—universities, presenters, funders, community organizations. This becomes a rubric as rigid as financial reporting.

MT: Yes! As someone who spends a lot of time on grants and reporting, I know how disproportionate the amount of labor spent on writing is in relation to the grant itself.

IS: It’s crazy. We spend most of the time writing the grant proposal and writing the report for a grant that doesn’t even cover the fees of writing the proposal or writing the report. I just wrote a proposal for a $5,000 grant. If I had to pay someone, it would be $60/hr for 40 hours, and it’s only a $5,000 grant.

MT: It’s the problem of the institution. You’re a company, you’re a non-profit, but these funders require you to be an institution. The value system is the problem.

IS: It keeps up the culture of white supremacy. You must have all of these resources and models and none of it is about the actual people. Most of the requirements for these high-level metrics are trying to say that the quantitative aspects of the finances and the narratives of the proposal are speaking together, but we know that is not true, especially when we look at people of color. If you understand the wealth gaps in our society, there is no way that it can actually be true. It can only be true for the biggest of the institutions that the quantitative and the narrative are speaking to each other because it’s only speaking to a specific demographic. We need to stop fooling ourselves in that regard.

I do think that there are people who are willing to hear it. I think now is the time. Can we all dismantle the systems together? That’s where the work is, and I’m not sure everybody is comfortable enough in their institutions to make this change. Let's do it, just do it. We hide behind “oh it’s gonna take a long time.” No it won’t! That’s a fallacy. That is the metric of keeping white supremacy alive, that it will take time. No, it takes one vote to change your by-laws, so why shouldn’t it take one senior administrator to say we changed the policy.

MT: It sounds so collaborative. You’re the Artistic Director, but it sounds like you’re not saying “do this, move there…”

IS: I don’t think I ever engaged in a place that wasn’t collaborative, in terms of my Blackness in an organization. I think that’s also a myth that came up from white supremacy, that collaborating is the new thing. Even when I was a student at ‘Danco, all of the choreographers always asked questions and gave the dancers tasks. There was a clear delineation of power or liability—the choreographer or Artistic Director at the front of the room is responsible if maybe someone gets injured. Someone has to have accountability. Yes, the work is deeply collaborative, but that’s not a buzz word I adopt because I’m about working with people and we’ve always been about working with people, being inclusive. You can’t be inclusive and not collaborate.

MT: When I see “Artistic Director,” I have preconceived notions—it’s hierarchical, it’s top-down, and it’s exactly what that cultural audit would reveal.

IS: Even in all of these conversations I’ve been in recently, I see myself as the Artistic Director or the Executive Director, as the center of a bicycle wheel with many spokes. I’m turning and looking at different spokes, but I am literally the conduit to make these spokes speak to each other. If you notice, there’s a bi-directionality to it. The spoke goes out but it also comes in. At every point, it’s not just out. I like being that kind of leader and changing the system. Language is important. We hear “Executive director,” we hear “board of directors,” and think top-down. How can we adopt and embody the idea of African philosophy where we’re a community of individuals, but we all feed and take from and give to the community as a model for how organizations run? That’s really what I'm trying to promote. They hold me accountable too. My dancers are like: “no!” “Why are you doing that? That ain’t what you said.” I have to apologize and recreate that space.

Interview with Iquail Shaheed of Dance Iquail, June 25, Zoom.

Photo credit: DANCE IQUAIL! photographed by Rachel Neville. (c)2020 DANCE IQUAIL reserves all rights to this image.

By Mira Treatman

June 26, 2020