What images come to mind, and who do you picture when thinking of the history and formation of American modern dance?

Border Crossings: Exile and American Modern Dance 1900-1955, curated by dance scholars Ninotchka Bennahum and Bruce Robertson, highlights the lives and work of immigrant and BIPOC dancers whose contributions have been largely erased in commonplace historical dialogue. The exhibition at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, until March 16, pulls from the rich archives of its Jerome Robbins Dance Division.

I asked fellow tD writer and editor Jonathan Stein to chat with me about the show and encourage readers to see this powerhouse of an exhibition and revision of canonical dance history.

Emilee Lord: It’s humbling to discover what you don’t know. The degree to which modern dance was influenced by folks who were then erased from its storyline is not surprising, unfortunately. There were major influences and incredible dancers I had never heard of. I left the show on fire about dance and how it is made, who makes it, and why they do it. There was a lot to absorb and unpack.

Jonathan Stein: I think beyond the discovery of a long list of artists who have been marginalized or forgotten in early modern dance history, I was struck by how American modern dance is this artistic and cultural hybrid. There’s a synchronicity of art making and cultural sharing that this exhibition highlights, where artists value and pursue multicultural investigation.

EL: Can you say more about this?

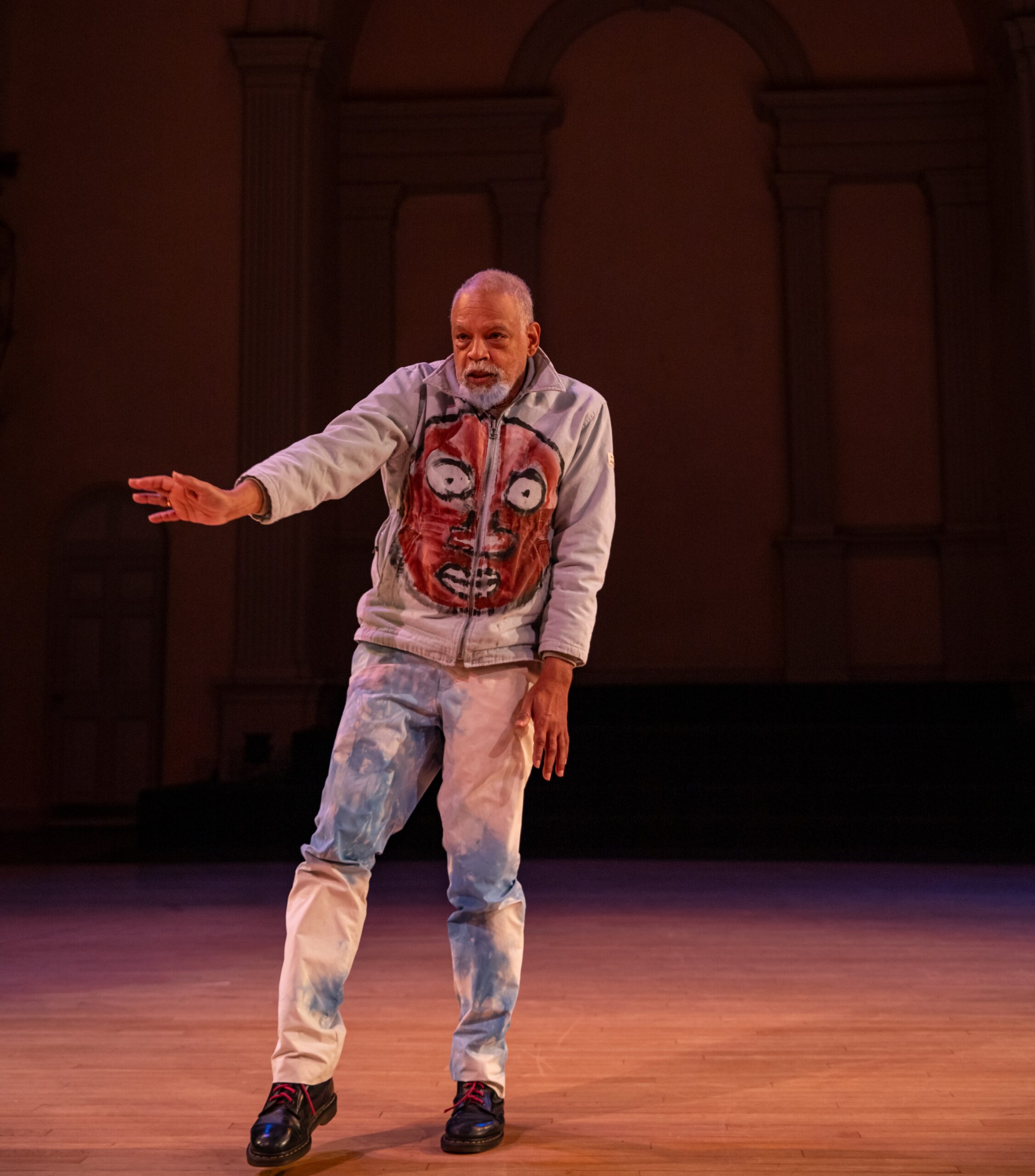

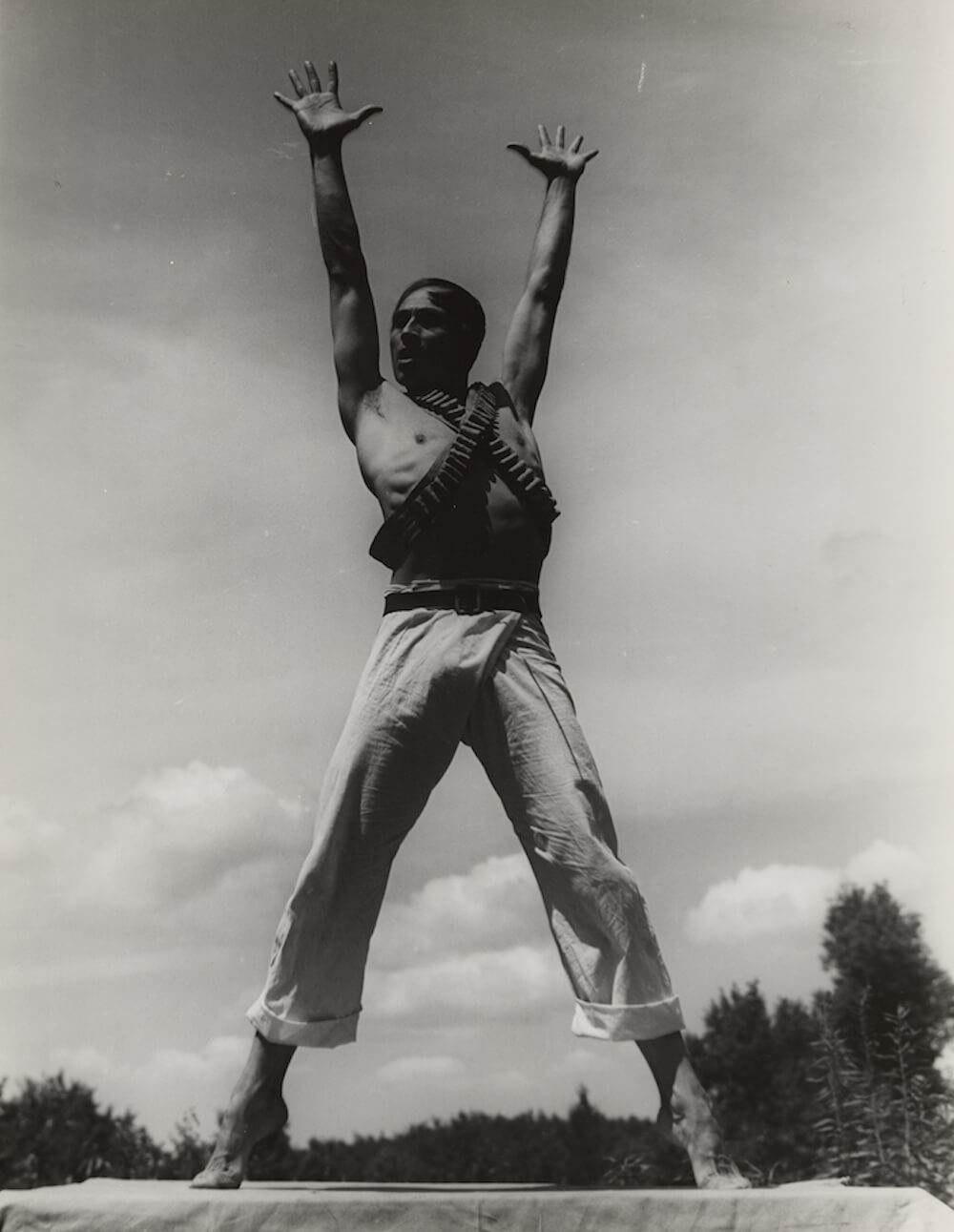

JS: There is an undercurrent of cultural investigation and curiosity that’s evident in many parts of this exhibition. Katherine Dunham and Pearl Primus, for example, became dance ethnographers and cultural anthropologists, finding the roots of modern dance in their research of Afro-Caribbean and African dance, and dance of sharecroppers of the American south. Or José Limón who came from Mexico and infused modern dance with a social justice imperative. But amidst these explorations, there are the structural restraints of racism limiting dance opportunities for dancers of color.

EL: Dancers of color were teaching into, giving what they had to, the hybrid pool that was becoming modern dance, but then they were barred from stages and studios.

JS: As the exhibition documents well, this led to the formation of the first Black dance companies and schools in the 30s, such as Eugene von Grona’s American Negro Ballet Company and Dunham’s School of Dance and the Dramatic Arts.

EL: The sections of the show called “Race and Ballet” and “Early Jazz Modernism” highlighted the nuances of the theme of exile. A lot of modern dance was made, informed, and catalyzed by exiled figures. Borders were created, and artists were exiled within our country, like Janet Collins, shunted away from ballet to be more successful in Afro-diasporic material deemed more “authentic.” The exhibition offers many definitions of borders and crossings and of exile, too.

JS: Yes, exile is a leitmotif for this exhibition; the wall text describes Anna Sokolow’s ‘The Exile’ as Sokolow “seeing modernity as a history of exile.” Sokolow went to Mexico to join Jewishness and Mexican folklore in her 1939 political dance. Amidst this multiplicity of borders, the exhibition also recognizes the arbitrary construct of the notion of borders, as dance educator Michelle Manzales states: “I am not crossing any borders. People have drawn borders across me.”

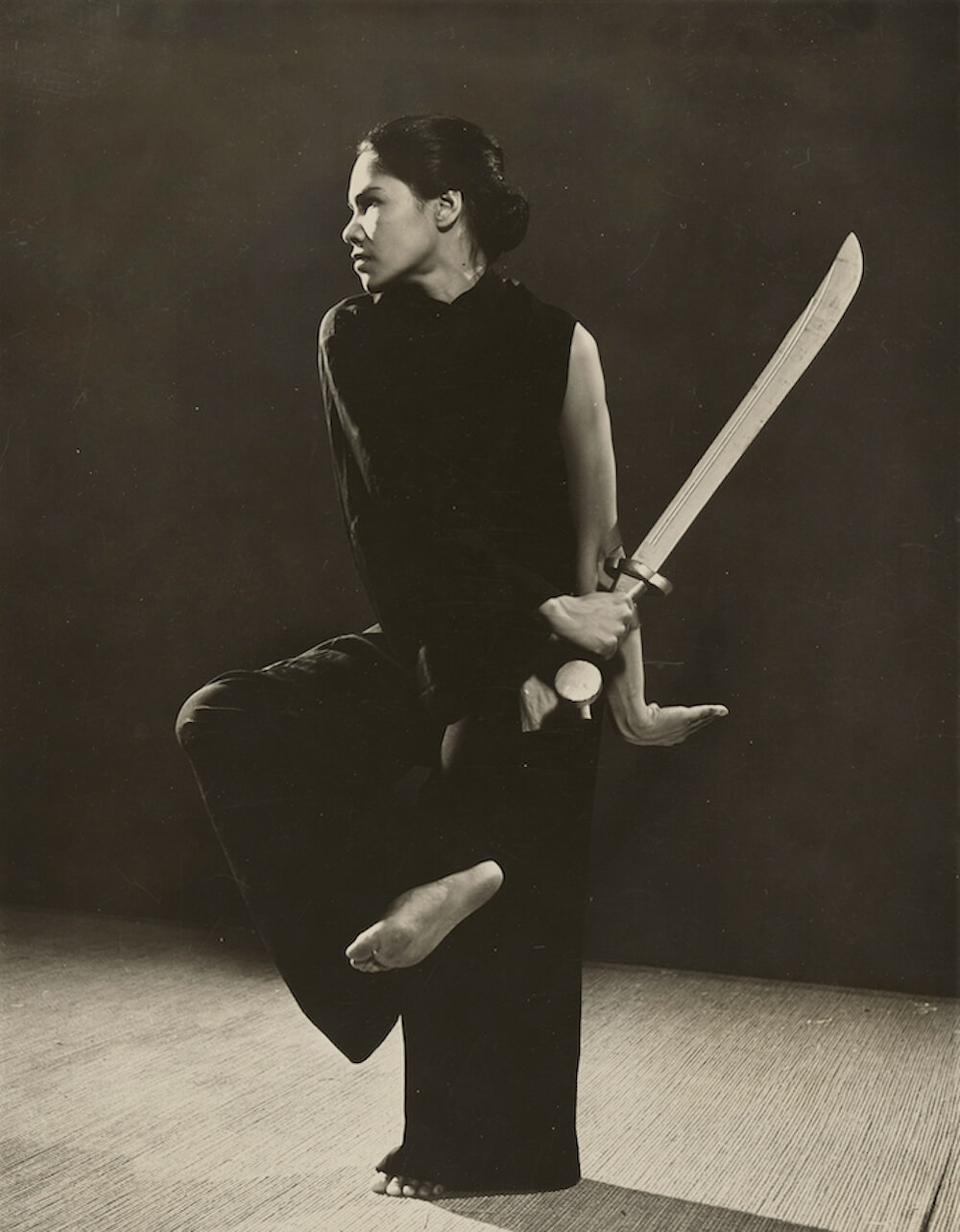

EL: Included among the many erasures of Asian artists was the Japanese dancer Michio Ito, who was arrested and held in detainment facilities before his deportation to Japan during World War II.

JS: There’s a glorious 1930 photo of Yeichi Nimura, another Japanese dancer absent from histories, leaping above an automobile in his samurai sword dance.

EL: One of the wall texts relates how some of the physicalities that we think of as iconic handshapes and stepping gestures in American modern were derived from Japanese and Indian dancers. They appear in the dancing bodies of folks like Martha Graham. But there is missing archival footage and photos, and this reflects what co-curator Bennahum refers to as archival silencing.

JS: The exhibition acknowledges the absence of documented history and the curatorial challenge of how to address archival absence. Many of these artists had limited access to venues and documentation, and many more stories can’t be told because of the absence of historical evidence. The exhibition holds space around these absences.

EL: And for all those absences, it shows a large and active global community of artists. They were studying each other, referencing each other or the moment in time, and expanding definitions of dance. People were asking, what can this form do exactly?

JS: The show extends beyond the often described aesthetic categories of dance to the crossings of political and social borders, as in the sections on “Labor and Radical Dance,” “Dance for Spain,” and “Bodies of War,” where socialism and anti-fascism imbued modern dance with impassioned movement for a more just society.

EL: This kind of dance wasn’t going to be entertaining, beautiful, light, and airy—it was embracing conflict. These makers were mining the body for its response to these things, as in the work of Edith Segal or Jane Dudley. They took the strong stances and musculature of the laboring class and put it on stage. The photographs show how much was going on in these bodies. It was a really active moment.

JS: Yes, the radical politics of the times allowed makers to use the radical body to respond to the traumas of war, class, and political conflict.

EL: It also raises questions about now. Are we questioning new hybrids? What are the new curiosities, but also the current struggles? Not that every work has to be a work of activism, but performance and dance are social engagement at the core. So, how are we affecting others? Are we thinking about that?

JS: It centers on the fact that arts can be a force of resistance, and this historical look asks of us, is art doing this today?

EL: The exhibition doesn’t dwell on aesthetics. It doesn’t provide you with text or movement analysis, but the aesthetics is something you glean through images in an exhibition so rich with photographs, many of which I have never seen.

JS: Not to mention over nine hours of film and video. You can spend a half hour with the films on jazz modernism—a 1903 film of the cakewalk, the film of Cab Calloway dancing the conducting of his jazz orchestra, or the Nicholas Brothers doing their breathtaking multi-level leaps into splits.

EL: The show flowed well, was easy to follow, and videos and photos broke up the text well. I did want, though, an image list for each set of videos. And I want to dig further and see more of this exhibition talked and written about.

JS: It warrants a serious catalog, not just a hand-out brochure. The brochures do have book recommendations for further study. The exhibition will hopefully generate interest in these periods for artists today and perhaps for larger institutions to do their own excavations into this past.

EL: I am hoping that people keep the NY Public Library for the Performing Arts on their radar because it’s a massive resource. No matter what you have studied, this particular show offers eye-opening places to reexamine, relearn, be humbled—then be inspired.

Border Crossings: Exile and American Modern Dance 1900-1955, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, June 8–March 16.

*Since the publishing of this article a catalogue has been made available for purchase here

Photo Credits:

homepage – Katherine Dunham at Villa I Tatti in Florence, Italy, c. 1949. Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

article header – Jane Dudley in Song of Protest, 1937. Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

Within article: José Limón in “Revalucionario” from Danzas Mexicanas. Photo by John Lindquist. © Houghton Library, Harvard University, and Si-Lan Chen. Photo by Eliot Elisofon. Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.