The Cannonball Festival shared two works from artists, each with a mother with dementia: This is How We Remember, co-created by choreographer/dancer Zoe Rabinowitz and composer Galen Bremer, and Love You, Love You, Love You, by creator/performer Sarah Sanford. Cannonball programmed each in one afternoon. tD writers Shayla-Vie Jenkins and Jonathan Stein saw the productions and added their own conversation between these performances.

Jonathan Stein: I was swept away by the emotional impacts of each work, which addressed similar subjects with different aesthetic choices, revealing different personal responses to these traumatic and all too common intergenerational occurrences within families. This is How We Remember’s engrossing and touching duets of Rabinowitz and Mary McGrath became an intimate exploration of a mother-daughter’s transforming relationship amidst their recurrent, joint memories, where physical proximity or distance, contact or loss of contact, could say so much. Love You’s compelling solo, performed by Sanford, let loose a theatrical broadside of the heightened emotions surrounding the parent’s dementia—confusion, rage, love, surreal flights, and absurd humor. It was fascinating and rewarding to see these different approaches. Shayla-Vie, your overview of these two works?

Shayla-Vie Jenkins: I love that we are having this conversation, allowing the work to settle in our memories and each day write a little about it. For me, our correspondence feels like an antidote to the ephemeral nature of performance and the exciting yet over stimulation of a festival.

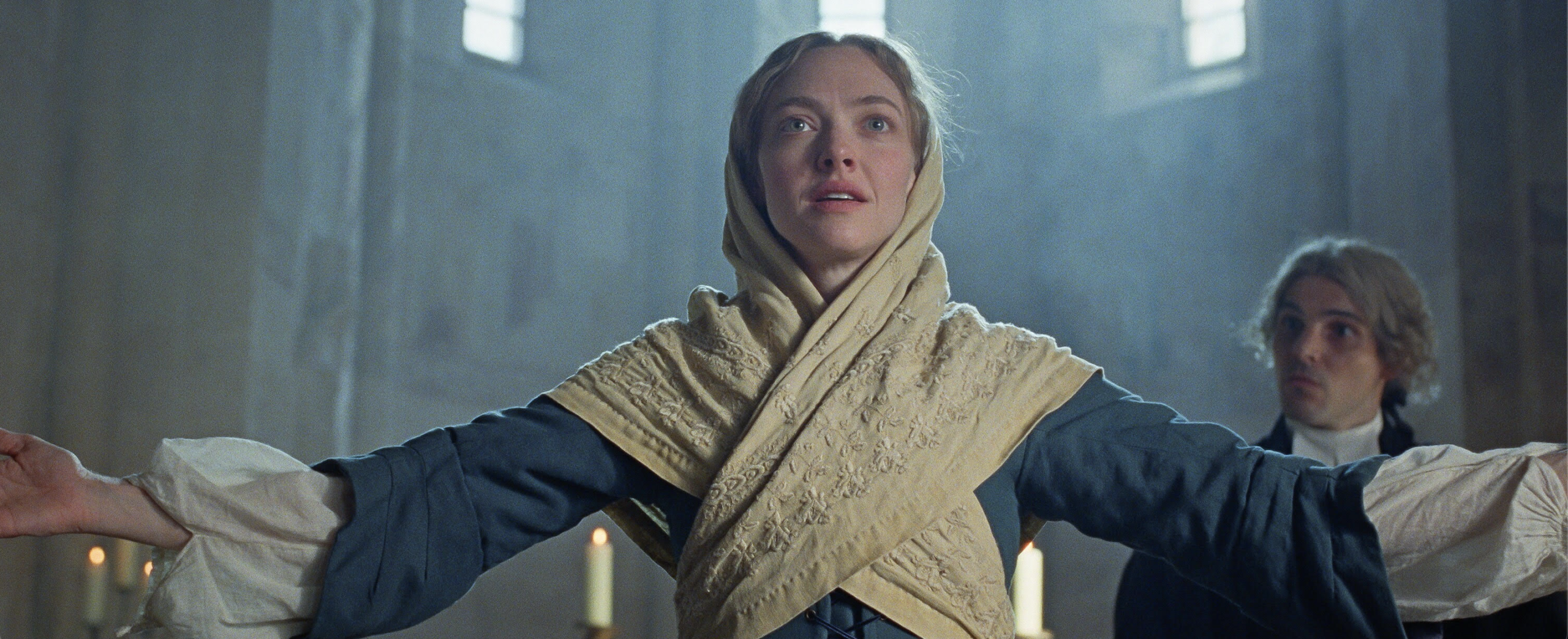

I was moved by both performances. Love You is a tour-de-force, one-woman show excavating this personal story through dance, mime, storytelling, and improvisation, evoking a wide range of emotions.This emotional breadth resonated with me. Sanford adroitly moved between laugh-out-loud absurdist humor, schmaltzy sensuality, heartbreaking confusion, concern, frustration, and rage. As a mother, and daughter of a mother from a similar time, I welcomed the range of heightened emotions. It felt profoundly authentic even in its absurdism.

In contrast, This Is How We Remember took a more subtle and abstract approach, using dance and video as its primary expressions. It felt meditatively slow, inviting us to pause, see more, and perhaps feel deeply as the dance unfolds. In the press release, Rabinowitz shared, “This is a performance about holding the reality of loss and suffering alongside the beauty and thrill of being alive.” I would also argue there is a sense of wildness in the urgency with which the performers clung to one another or in McGrath’s intense gaze. An underlying unease simmered beneath the surface, woven into the fabric of the work but not explicitly acknowledged. I am curious about what remains unnamed and unaddressed in this performance.

In both works there was a deliberate action of naming objects seen and unseen in the space, and a glitching of movement and textual language. If naming is our way of attaching meaning to the world, what happens when we lose those names? Does meaning disappear along with them? I’d love to hear your thoughts on the treatment of language in both works.

JS: The more minimal use of language in This is How We Remember worked, adding to its potency, and in contrast, made its silences strong as well, leaving space for the beautifully crafted soundscape and video projections of Galen Bremer. At its beginning, to Bremer’s fractured sounds and the subtle lighting of Connor Sale, Rabinowitz and McGrath, in parallel paths and repetitive phrases, first mumbling and then more audibly, count out steps in space. Their language set a theme of an obsessive effort to understand a more clouded reality. Because the work was a duet, it allowed both women to assume the same roles or to alternate between being the mother or the daughter, which I thought was a brilliant construction of how dementia can alter parent and child roles, suggesting to me that even without a parent with dementia, this switching of roles can take place at any time within families.

Later the minimal call and response of their Marco Polo hide-and-seek game on a darkened stage, and the daughter’s flashlight-lit hunt for her mother, joined frolicsome family play with the terror of a lost mother into one action.

Language was central to Love You, Love You, Love You, embraced by its title, which allowed Sanford to employ her stellar acting chops to explore the range of naturalistic and surreal aspects of her mother’s dementia, whether suicide ideation (taking her pills to Cape Cod) or fashioning her mother as a demonic witch who read a bedtime story. When I heard in Remember the words “have you eaten” and then later, its parallel in Love You, “when have you last eaten,” I was struck by this shared language of caring and anxiety.

Since Sanford is such a skilled physical actor, I am wondering what movement aspects of both works stood out for you?

SVJ: I agree–hearing echoes of care for such simple yet essential tasks struck a chord with me as well.

Watching Sanford’s performance I remember that she is a DANCER and maybe it’s that foundational training that informs her adeptness as an actor. There is an unpredictable physicality and wildness in Sanford’s movement that feels metaphorically akin to the Baby Yaga character in Love You. What stands out is the wide range of states that Sanford gets to embody: the way she juts her pelvis dancing to Michael Jackson while trying to remember a childhood dance. The weight of her shoulders slacken and chest collapse as she sits and looks at us in silence. The shuffling walk, and slight curl of the spine. The furious boxing match with her mother (a portrayal I wished lasted longer), and my favorite scene where she rocks back into a coccyx balance while unfurling her legs in the air at the climax of her self-pleasuring as Baba Yaga.

In This is How We Remember, the highlight for me was when the two performers finally come into sustained contact. Their embrace–slippery, deteriorating, and unsustainable–captures the escalating effort to hold onto a loved one slipping away.

Toward the final quarter of the piece, they return to the hug. McGrath turns away and leans forward, arms outstretched, her face full of wonder, as if she might float away, while Rabinowitz anchors and counterbalances her weight. The partner work is tender and deeply human as their bodies entwine, rest on each other, fall and receive. It is gorgeous and well earned. One of the lasting images I have of McGrath and Rabinowitz is their long hand-held counterbalance on one leg. They move apart but are held in a temporary equilibrium. I saw two beings, both mother/daughter/friend/young/old, asking what lies ahead and behind them.

JS: I agree with your observations. I might add Sanford’s clowning humor brought to mind the genre’s dark layering of sadness under the surface joking, quite fitting for the subject and akin in combining conflicting emotions to Remember’s hide-and-seek night scene. The stand-out moments in Remember were, in contrast to its joyful unison dance scenes, the repetitive partner embraces that first slowly then abruptly dissolved to the floor, leaving the standing partner’s circling arms embracing a void.

Bremer’s and Rabinowitz’s video and projections were especially evocative yet spare, as in the barely visible rivulets of water cascading off a gray hillside, reminding us of ineluctable transformations. At the end, a mother sits in profile, motionless, with calm waters beyond her.

This is How We Remember, co-creators, choreographer/performer Zoe Rabinowitz and composer/videographer Galen Bremer, Sept. 21-22, and Love You, Love You, Love You, creator/performer Sarah Sanford and director Alex Tatarsky, Sept. 20-29, both Cannonball Festival, Christ Church Neighborhood House.

Homepage Image Description: Two women standing in a spotlit space, each with a yellow top and white pants with the taller, Zoe Rabinowitz, gazing aside, embraces and holds Mary McGrath to her chest, one arm around her blond hair, the other around her back, her face buried in Rabinowitz’s chest.

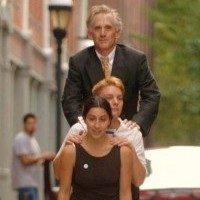

Article Page Image Description: One woman, Zoe Rabinowitz, with green hued lighting behind her, is carrying horizontally across the front of her torso, Mary McGrath, who is lit with green and red hues across her outstretched body. Rabinowitz gazes forward beyond McGrath, who lies motionless on her back across the supporting arms of Rabinowitz.