I’ve been to many dance performances that ended with a dance party. I’ve never been to one that began with a dance party. That is what I find when I enter Christ Church Neighborhood House on a steamy Saturday in June for The Re-Emancipation of Social Dance by Raja Feather Kelly and Yolanda Wisher. The energy is infectious. Everyone is getting down, sweating through sundresses and patterned button-downs as they move to the beat. Kelly is on a mic and on the dance floor, hyping up the dancing as more audience members stream in and join the party: “You know if you dance a little bit, it’s so much easier to move through the crowd.”

Donna Summer’s “Bad Girl” begins and most of the audience forms a giant conga line, snaking around the room. I take this as an opportunity to find a seat and soak in the way the typical black box theater has been utterly transformed. With no marley laid down, I can see the plain wooden gymnasium floor with the scuffed markings of a basketball court. Chairs, chaises, floor cushions, and couches ring the space with string lights and streamers hanging overhead. A neon sign reads “open late.” Behind the chairs, there’s a variety of lamps, stacked books, mirrors, and clocks.

Throughout the night my sense of location morphs in response to this welcoming, maximalist design and the performers’ storytelling. We’re at a house party, a gay club, a middle school dance, a jazz bar, a dream world, somewhere hip and timeless and tinseled.

“What does it mean to re-emancipate yourself?” – The question reverberates over the speakers.

The audience takes their seats around the edges of the space. The performers emerge from among them, declaring themselves from among the fluttering of fans and programs. Each artist shares their personal relationship to a variety of African diasporic social dances, while weaving in the political and social contexts in which these dances formed. The stories spiral, switching between performers who primarily inhabit the space as soloists, each artist offering their own understanding of how social dancing can be emancipatory.

Germaine Ingram embodies dance as sanctuary while remembering the parties she attended as a Black grad student at Penn. She moves with a metal bowl as her partner, translating the sway of her hips through the container as she tells us about the refuge they created, dancing in small rooms with the couches pushed up against the walls. Above the tightness of her spatial navigation her arms flow, sending endless rivers of energy – a testament, a broadcast.

Lela Aisha Jones draws our attention to the body as the site of freedom. In a bright red suit, she becomes jazz, she becomes a visualization of the music. A tight zigzag motion in the shoulders, a gooey descent towards the floor. A visceralization of the sound, of the moment, of our collective presence. Later she calls forth the ancestors, a bell ringing as she moves, now swamped in red tulle over the red suit. If the body is the site of freedom, connection to lineage may be the precondition, or at least one place where a person can find the strength to practice freedom.

Vitche-Boul Ra enters through an incredibly slow back bend, eventually sliding onto the floor. Ra’s movement draws heavily from voguing and ballroom, using suspension and pause to tease us with anticipation. Ra takes us into a queer, futurist dream world as It* climbs onto a wooden platform in the far corner of the room. Sitting in a straddle across the wooden beams of the platform railings Ra speaks a poem with popping diction. I cannot make out the words but experience each utterance as an insistent clap. From the platform It descends on a plastic slide, swooping across the space with wild momentum, a cresting wave of somersaults, bounding steps, and windmilling arms. Electrified by this wave of kinetic energy and risk, I think that freedom is the ability to dream and that dancing allows us to dream together.

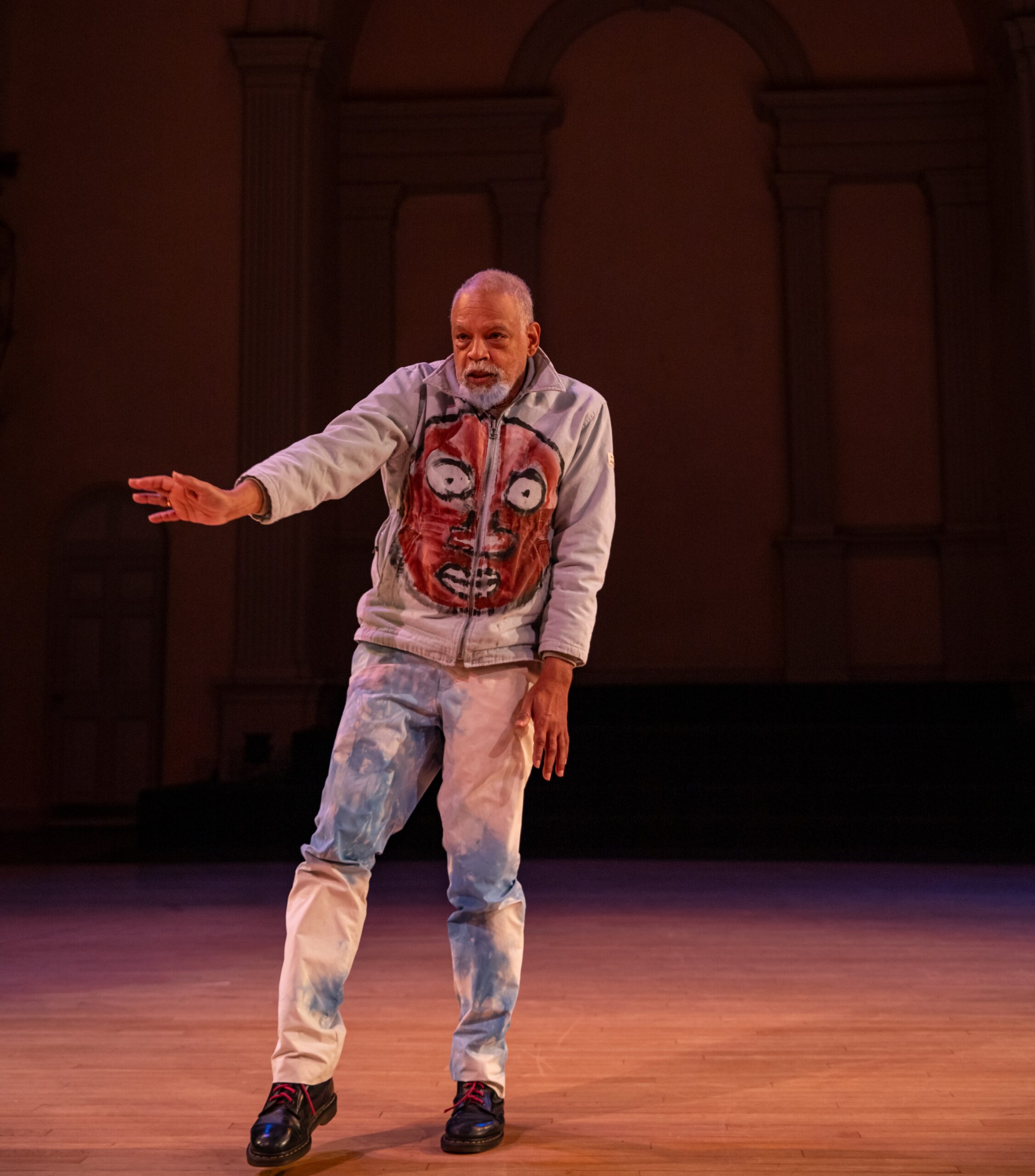

Mark “Metal” Wong shares the complications of entering deeply into an African diasporic form as a non-black dancer. He begins by contextualizing breaking, teaching us the elements of the form and attributing its creation to the abundant creativity and playfulness of young Black boys, as young as 9 and 10, in the 1970s Bronx. Later he shares that when he first began breaking he was told by his mentor that the cypher is a conversation. If you don’t want to be laughed out of the cypher, you have to add something of value to that conversation. Late in the performance, he draws on his Chinese heritage, undressing while telling a folk tale about Lao-Tzu and an archer. The story is about transcending the goals and techniques of a form to find pure expression. In bare feet and boxer shorts, he performs a breaking solo defined by suspension and tenderness, a languidness mixing with the moments of power and attack. His freezes are like the top of an inhale rather than a block of ice. In the arc of his performance throughout the night, I see an example of how a dancer can respectfully and authentically engage in dance form from a culture not their own.

Nikki Powerhouse opens and closes the performance, conjuring her father: “My daddy knew freedom, but only on the dance floor.” She brings him alive with quick steps and a bounce through the knees. She shows us how her daddy would bend over towards her, arms wide, saying: “Who loves you, baby?” Maybe dancing is the way to love. Maybe dancing is the way to connection, as Kelly seems to indicate as he instructs us midway through the performance to stand close to one another and hold eye contact through a song, re-enacting the hesitant intimacy of a middle school dance.

The phrase “the re-emancipation of social dance” could be read as a reclaiming of social dance forms that have been commoditized – returning them to the contexts, communities, and relationships that forged them. But it can also be read as a statement of the power these social dances have to allow the practitioners to find freedom, over and over again. The richness and pleasure of this performance lies within Kelly and Wisher’s insistence on multiplicity and multivocality. Even more of which can be found in an accompanying podcast series on the project’s website.

* Vitche-Boul Ra uses It pronouns.

The Re-emancipation of Social Dance, Raja Feather Kelly & Yolanda Wisher, Intercultural Journeys, Christ Church Neighborhood House, June 22.