“The Geiger of death crackles through the room.”

This line from Paul Monette’s book Love Alone: 18 Elegies for Rog haunted me when I read it, and it jumped out again for me tonight. It is just one of many moments in the Love Alone Anthology Project that will linger in my chest for a while.

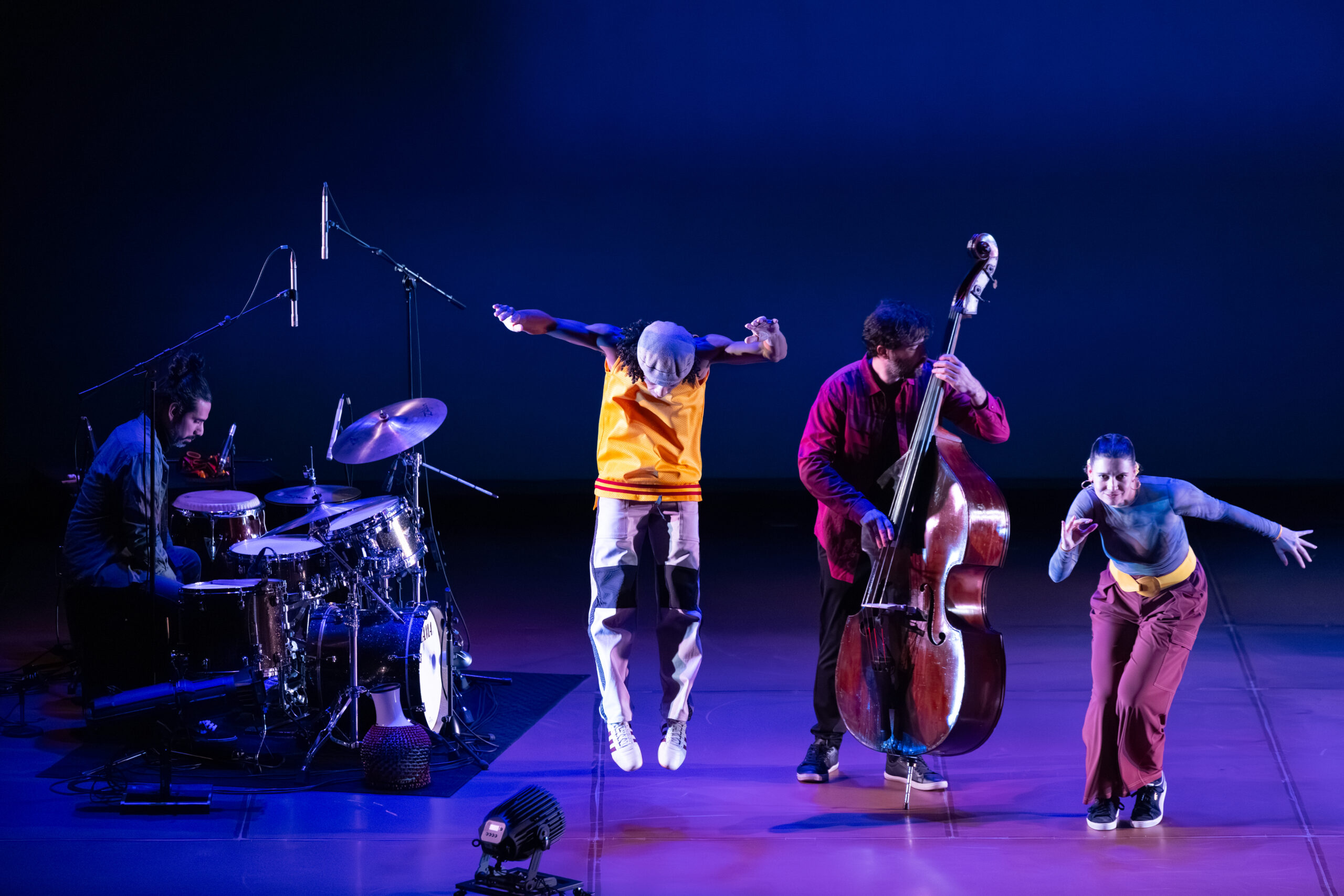

I wrote about a solo portion of the work in a triple bill evening at The Tank NYC a couple of years ago. Choreographer Keith Thompson and the danceTatics performance group have been piecing together the evening-length version for some time. It premiered last night as part of La Mama Moves Dance Festival in NYC. This interdisciplinary work is based on the book of poetry by Monette, written at the height of the American AIDS epidemic as his partner was dying. Thompson’s piece is structured as a collection of dance/theater chapters named after specific poems in the book. Each piece can be shown individually or as a whole. The evening of solos, duets, and trios performed by Clarence Brooks, Shawn Brush, Aidan Feldman, and Brendan McCall has a tenderness about it, somehow akin to caring for a wound that never quite heals.

The use of the text changed with each chapter; at times, the dancers spoke the elegies, and then we might hear a voiceover. In one scene, Brooks brings a chair far downstage into a warm spotlight and reads to us as Brush dances in a muted red tone behind and around them. Brush remains within the vocabulary already established, though perhaps it builds in flickers of abandon. The text is painful—a carefully timed lilt of sorrow, longing, effrontery, defiance, and desperation. It is not surprising, subject matter aside, that Thompson was drawn to move to it. The writing has a somatic quality, and again, this timing drops in and out of its various needs.

The choreography is full of gestures, small and large, that we see repeated thematically throughout the work–calling us back, linking sections, and layering up over time. Covering faces, faces pulled by hands, looking at hands, hands leading knees to bend, bends, breaks, and wide slices. There are ticks, big leans, and lifts in the partnering, playful taking-over of each other’s space. The dancers are not assigned characters so much as they embody the text together, sometimes Rog and sometimes Monette, and remember the words are always from Monette in the end. Rog is gone. In the trios, Brooks appears to represent something between the two men. Are they embodying the grief, the love? They may be the space in between them, and they may be the text itself given a body on stage to contain it. It enlivens the moment to wonder these things while the three move seamlessly through unisons and cannons.

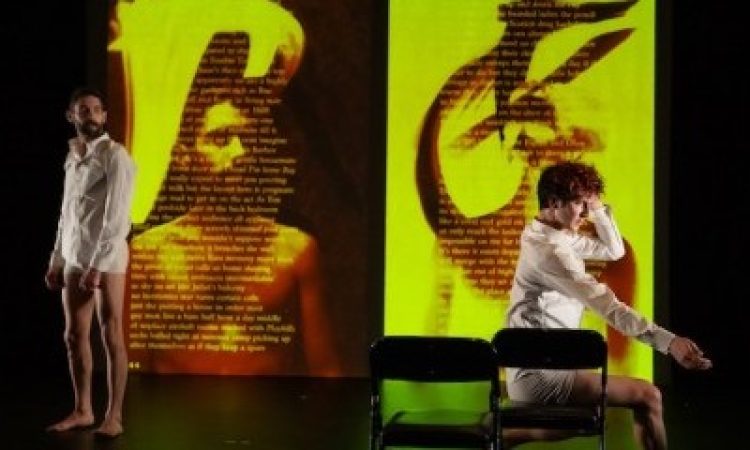

Visual artist Robert Flynt took all the photographs and David Fishel made all the projections playing behind the dancers throughout the work. They are visceral images, often on split screens, with photos of the performers nude, sometimes together, often alone, curled in fetal positions, holding faces in hands, reaching. Layered on top of this is a series of images and the text from the book, another way it is present throughout the evening. Initially, the layers are maps, then objects of daily life, then medical illustrations, bones, fragments, lungs, and nerve systems. Near the end quickly shifting photos as if a stop motion were made. It turned into a split screen rotation of the performers making hand gestures around their faces in a way that references vogue culture. Still, the gestures are a little more startling and less precise–a fist shoved into a mouth, a hand cutting the face in half, looking side to side, face in hands. The visuals are such an integral part of the work and add layers and layers of complexity, vulnerability, and intimacy to something already so imbued with these things.

Love Alone Anthology Project is brutally beautiful. Quiet and outraged, sometimes funny, always pleading and loving. It’s all so tender and full of longing. Full of the very specific ways Monette was grieving his lover and his community. The sense of empty arms and grief is thick enough to smell. “Pain is not a flower,” one dancer states plainly in the opening duet called Gardenias. Pain is not a dance either, though this one hurts, even as you may smile or are wooed.

Love Alone Anthology Project, dancTactics performance group, April 10 – 13, La Mama NYC

*Brendan McCall is a recent writer hire for thINKingDANCE and has guest written for tD twice in the last year.