Five months after its February 24 premiere at Bryn Mawr College, John Jasperse’s Fort Blossom revisited (2000/2012) is still worming its way through my mental hard drive. If the artist’s intention was to baffle his audience with the most fundamental questions about the relationship between nudity and sexuality, about the representation of bodies on stage, about the artist’s responsibility for the socio-political implications of his work – then Jasperse has succeeded.

Several people have written – some beautifully – about this piece, which has become known for its showcasing of the male “buttocks and its interior.” I remember sitting in the front row, keen to witness this obliquely sexual dance unfold. Now, I sit at the computer, anxious to express an aspect of my viewing experience that goes beyond what actually happened in the theater.

Flashback

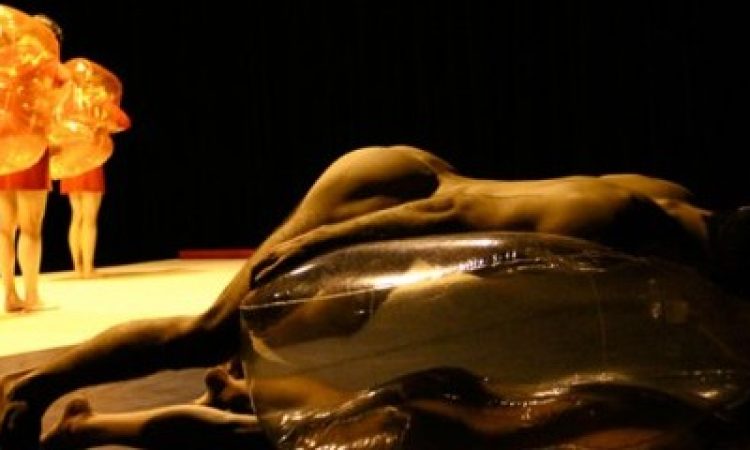

Dim industrial lights flickered on and hummed overhead. Ben Asriel, one of Fort Blossom’s four dancers, walked onto the bare stage. He lay in the front, face-down, naked. The lights changed from white to orange to peach. A high pitch softly penetrated our ears as the other dancers entered the stage: two clothed women and Burr Johnson, also naked. He carried with him a transparent inflatable pillow, onto which he splayed his body, also face-down, his inguinal region in full view.

What ensued was a slow, deliberate, exploratory dance. Asriel inched forward like a caterpillar, lifting up his hips, exposing his scrotum, then creating a wave through his spine while dragging his calloused feet behind. Johnson hugged his pillow as he rolled sideways towards Asriel at the front of the stage. Minutes later they met. Johnson rolled on top of Asriel; the pillow separated their bodies. They ground their hips in a simulated sex act as the pillow gradually deflated.

The male bodies became central to my continuing questions about Fort Blossom. In the pivotal duet, the men conducted a controlled laboratory search using their bodies as tactile instruments. I imagined the choreographer’s directives: “Touch your anus to your partner’s every body part, except his hands, face and genitalia.” My attention peaked midway through this 20-minute experiment, when Johnson slid his perineum down Asriel’s shin. The juxtaposition of fully dressed women and buck naked men was easily read as a reversal of onstage gender roles. The formal, synchronized dance of the women versus the slithering, organic entanglement of the men also set up an accessible contrast. But I was unsure whether to view the naked bodies as “sexual” – or, indeed, “homosexual” – or as anatomical abstractions. And this raised a whole bunch of questions for me.

I found myself curious about Jasperse’s intentions, as I would be about any artist whose work is read by much of the public as “gay.” What is the artist trying to tell us naked gay male bodies can do – or signify – that other bodies can’t? Is the naked gay male body supposed to provoke – or perhaps comfort – the audience with its difference?

In our multi-media era gay sexuality is still either muted (a sexy homoerotic scene on broadcast TV remains a rare find, even on shows with “well-rounded” gay characters) or pornographic (hello, Internet!). Jasperse’s depiction and abstraction of gay sex resides outside the continuum between these two poles. During the extended duet, the viewers grew comfortable – or at least desensitized to – gazing at the male body. I appreciated this.

Indeed, after the performance at Bryn Mawr College, a well-respected institution with a progressive liberal culture, I overheard several audience members refer to their expanded appreciation of the “beauty” of the male body – as if this were a surprise. But the beauty of anuses and sphincters, ball sacks and butt cracks, penis heads and foreskin were inscribed by Jasperse on the bodies of “gay” men – and this matters.

The Rabbit Hole

During and after the performance I perceived myself, as a gay-identified man, to be reacting differently to the dance than my female colleagues. I felt – empathetically – like my body had just been consumed onstage. My unease stemmed not so much from the nudity itself, but from the two male nudes together. I felt triggered and bored at the same time. This might have been intentional on part of the choreographer, and perhaps necessary – and it sent me down a rabbit hole well beyond the purview of this performance.

Just days before, neighboring Villanova University had cancelled a week-long acting workshop by openly gay performance artist, Tim Miller, citing the incompatibility of the University’s Catholic values with Miller’s “edgy” work – which sometimes includes nudity. Clearly, the issue of public male nudity still pushes buttons among some in our culture. Indeed, a colleague of mine who chairs a dance department in Central Pennsylvania stated that she could never bring Jasperse’s piece to her liberal arts college, not because of the homoerotic subtext, but because of its explicit sexuality. (She read Fort Blossom as “sexual” rather than “nude” – I took note.)

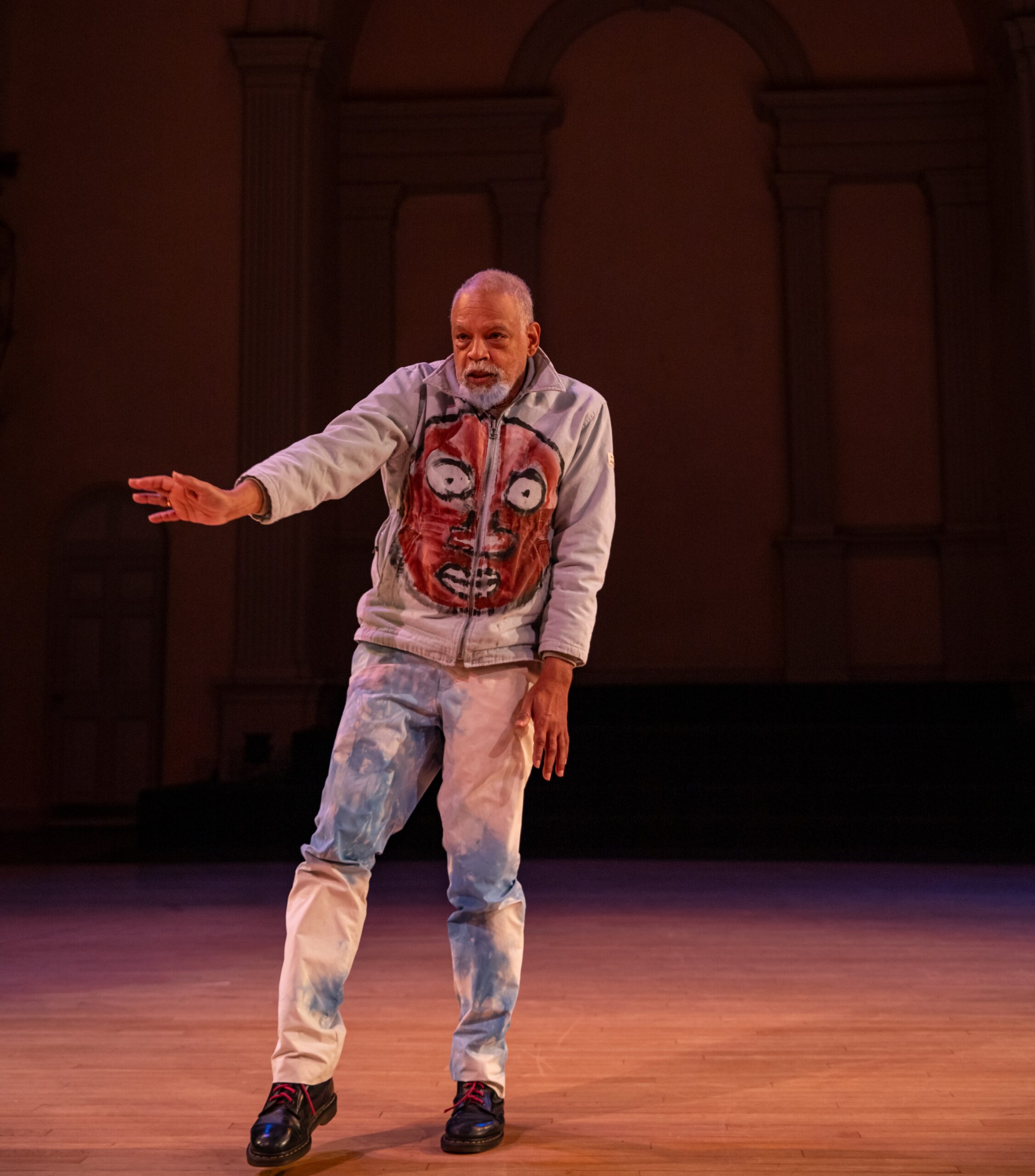

The morning after I saw Fort Blossom, I had lunch with a friend currently running for office. If elected as State Representative of his Central Pennsylvania district, he’ll be the state’s first openly gay elected official. This historic circumstance helped me crystallize a question prompted by the prior evening’s performance: What are the political implications of choreographing a naked male duet in 2012?

Former Republican vice-president Cheney as well as sitting president Obama are championing marriage equality. LGB soldiers are now allowed to serve their country openly. Ellen is the new Oprah. And yet, it is still perfectly legal in many parts of Pennsylvania – and in 29 other states – to suspend employment, deny housing and refuse restaurant service to people who are suspected of being gay or transgender. 30% of homeless youth are LGBT; and one in five children of LGBT couples live below the poverty line (twice the rate of heterosexual married couples). LGBT families are taxed at a disadvantage (because parents can’t marry) and often have to pay high fees in custody or adoption cases to maintain a legal relationship with their own children. This is not to speak of HIV-infections, a piece of a larger health-care crisis that disproportionately affects LGBT folks and is far from over. In other words, LGBT communities still need to navigate a careful, and collaborative, political strategy – especially beyond urban centers – in order to secure basic human rights. Should it matter what role Fort Blossom plays in this socio-political context? And what privileges might this work take for granted?

The gay male body (never mind the young, white, fit gay male body) means a lot of things to a lot of different people. When Jasperse establishes binaries between clothed women and naked (gay) men, between formalist and improvised dance, between shock and repetition, he does so for audiences who carry their impressions beyond the theater. None of these contrasts can ever be completely abstract. Nor should they be. Meaning lingers in, and is constructed around, each choreographic choice.

A Can Of Worms

And therein lies the question about responsibility. Why use the gay male body as the vehicle for reversing gender roles, contemplating male anatomy and/or exploring a formalist idea about performance? And to what end?

One thing that viewing the piece did for me was to abstract my sex life: for weeks afterwards, my sex-drive was deflated, because I kept imagining myself in a self-referential, loveless, sexless matrix of anatomical possibilities. This was one effect felt by one person. But my reaction makes me wonder what the work communicates to its multiple audiences about gay sexuality and, in turn, how these audiences relate that information to equal rights efforts that rely on voters, judges and politicians to secure, affirm and protect a minority’s equality under the law. The fact that I’m still thinking about Fort Blossom months later speaks to its genius. But it took time for me to recover from this piece – recover a sense of privacy when I’m naked, a taste for choreographic abstraction, a non-cynical appreciation for contemporary art’s ability to transform communities. And I finally worked up the gumption to publish this dang essay. As a reviewer, it’s scary to publicize my opinion about an artistic product whose intentions may be intellectually rigorous, but also open a can of worms. Even if the artist were to give me a logical explanation for his choreographic choices, what I saw were two ambiguously intimate male bodies, presented without context or history, bleeding meaning with every motion, impacting how I see myself and how others see people like me.

Ultimately, I return to my question whether the nude and intimate gay male body is used to provoke and/or to comfort the audience. As a perceived member of the group that Jasperse represents – in perhaps its most vulnerable state – my response is personal. I’ve spent months questioning the validity of my reaction. And yes: I have been provoked. This speaks to the ability of Jasperse’s art to move beyond the theater. That’s power. That’s art’s potential. Some might find beauty in Jasperse’s choreographic abstractions. But my quiet discomfort about Fort Blossom’s use of the gay male body has impacted my self-perception in ways that I feel are out of my control. I feel the opposite of comfort, the opposite of power.

Jasperse has opened a can, and the rest of us are left to chew on the worms. Some may call this the artist’s role in society, but I question who ends up being forced to do the chewing, and who is left hungry altogether.