Fix Me begins with the two creators and performers, Ben Grinberg and Hazem Header, lying on their sides in the upstage right corner of Fidget’s dance floor. Illuminated by an old-fashioned standing lamp, only Grinberg’s one bare leg is visible over Header’s hip. Slowly they wake, reaching arms up the lamp, legs up the white wall. They softly tumble over one another, switching places in a repetitive cycle. Grinberg balances on his head, legs reaching towards the ceiling while Header sits, resting against his torso, posing for us. Until Grinberg’s legs slowly descend upon him, upturning him. Their positions are reversed, an almost mirror image.

This doubling occurs in intervals throughout the performance. It is deployed through unison choreography: standing poses leaning against the wall, a rollicking short phrase of jumps, chugs, and turns. It also occurs through the language of acrobatics: a mirror created quite literally by Header performing a shoulder stand on Grinberg’s shoulders, one body reflected across a vertical axis. There’s a recognition of one another and a blending. I saw them both as the same person and as entwined lovers, reminding me of the queer quandary: do I want to date him or be him?

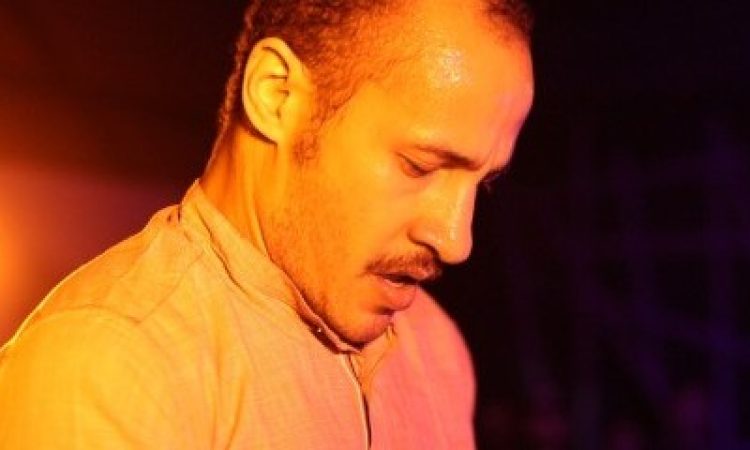

Though the doubling motif is prominent throughout, Header and Grinberg diverge into separate characters as the piece goes on. In their first major divergence, Grinberg moves to a couch on stage right where he strips down to some tight briefs and takes a series of thirst traps—first selfies and then more elaborate shots with the help of a recruited audience member. While Grinberg poses in increasingly comic ways, Header, on the other side of the space, bounces repeatedly on his knees, standing, hunched over. I see playfulness in the bounce on his knees which transforms to prayer or pleading as he bows his head to the earth, still pulsing with the beat. Upright, his groove places him in a club. Hunched over I see him dry heaving with disgust. Header’s face is a cool mask. At moments his bouncing is interrupted by the delicate reach of a hand, one pinky outstretched.

Later, Grinberg and Header portray variations of a sexual relationship. They play on the ways acrobatic techniques often require intimate closeness between faces and genitals, hands and inner thighs. In a somewhat slapstick section, Header repeatedly tries to kiss Grinberg who evades at the last second by slithering and tumbling away. I read Grinberg here as a closeted man. He feels the draw to Header but, despite the closeness of their bodies, cannot bridge that final gap.

The most emotionally potent moment occurs after they portray an act of oral sex. Grinberg ducks behind a curtain upstage to splash water on himself and Header follows, trying to embrace him. Grinberg roughly pushes him away. This action repeats several times growing in aggression and intensity until Grinberg disappears fully behind the curtain. We witness Header, with a dopey heart-sick smile on his face, launch himself over and over, embracing the absent air and thudding to the ground.

Throughout the performance Header seems to play a more consistent character. Someone searching for closeness and recognition—in the mirror, in the capacities of his own body, in a lover. When Grinberg is not forming Header’s double, he shifts between several related characters: the sexually expressive thirst-trap Grindr user, the closeted man avoiding a kiss, the hook-up down for pleasure but refusing affection.

Reflecting on the title, I wonder, who needs to be fixed? Is it Header? Was his bouncing bowed head a prayer to not be gay? Is he wishing to be more lovable or to not feel the yearning for affection? Or is one of Grinberg’s portrayals the one who needs to be fixed? Why can he not receive a kiss? Why is his emotionally-numb gay American man only open to physical pleasure? Though grown in radically different cultures both seem stuck trying to unravel the problems of intimacy and sex.

Grinberg and Header end the performance by breaking out of their characters and inviting on stage “anyone who thinks they are going to hell, or who thinks other people think they are going to hell” and “anyone who would like to kiss an Egyptian.”

This is an early showing of a work-in-process that will premiere this fall in Philadelphia’s Cannonball Festival, of which Grinberg is also a producer. In the post-performance conversation he shares they are interested in the divergences between the queer male experience in Egypt and the United States and what this might reflect on the relationship between these two nation-states. These larger political themes and cultural narratives appeared primarily as subtext in this version, with the exclusion of a brief moment of text in which each names the other’s identities, and the interactivity with the audience offered at the conclusion. I’m curious to see how they will bring these themes further to the forefront in future iterations. Despite the cultural differences they refer to, I found myself attached to them as individuals onstage, more than as representations of their respective nations. It’s a tricky artistic problem to hold both the intimate and the political, and I’m looking forward to seeing how they resolve it.

Fix Me (working title), Ben Grinberg & Hazem Header, The Fidget Space, May 8. The finished piece will be presented this September at the Cannonball Festival.